Maryland sees jump in use of program that pays jobless benefits for those brought back part-time

Only two companies were participating in Maryland’s work-sharing program at the beginning of this year. Since the novel coronavirus pandemic sparked widespread business shutdowns that decimated the economy, more than 225 have begun to take part.

And state officials are trying to spread the word.

“Rather than lay off employees, the alternative that we have available is you keep your workforce intact during tough times,” said Bryan Moore, deputy assistant secretary for the Division of Unemployment Insurance in the Maryland Department of Labor. “It’s been one of the better-kept secrets, and now we’re trying to let everyone know about it.”

Similar layoff reduction programs are operating in the District and about 25 states, including Virginia, California and New York.

Before the pandemic, the largest number of companies using work sharing in Maryland at any one time was 12 — and that was during the lean years of the Great Recession, Moore said. For the past several years, the state’s unemployment rate was low, and there was little need for the program.

Those employers who did apply went through a stringent review to determine whether their industries were in crisis, Moore said. Many did not qualify. But under rules put in place during the pandemic, any business that was ordered to shut down is eligible.

Under the program, a small-business owner could bring back 20 workers with a 50 percent reduction in hours, for example, instead of 10 employees at their normal hours.

The company pays the workers for 20 hours, and the state gives the employees 50 percent of their normal unemployment benefit. If an employee qualifies for Maryland’s maximum weekly benefit of $430, the worker receives $215. Companies can participate for up to six months.

The federal government reimburses the state for its costs, and Maryland companies enrolled in the program do not face an increase in the unemployment insurance tax.

“I call it a triple win,” said state Sen. Katie Fry Hester (D-Howard), who became aware of the program in April and launched a mini-campaign of her own to encourage the state to make small businesses owners aware of its existence. “It almost seemed too good to be true.”

Fry Hester said state analysts estimate that if 15,000 of the state’s jobless-benefits claimants participated in the program, Maryland could save about $46 million in its unemployment insurance fund at a time when state officials are worrying about the fund being depleted.

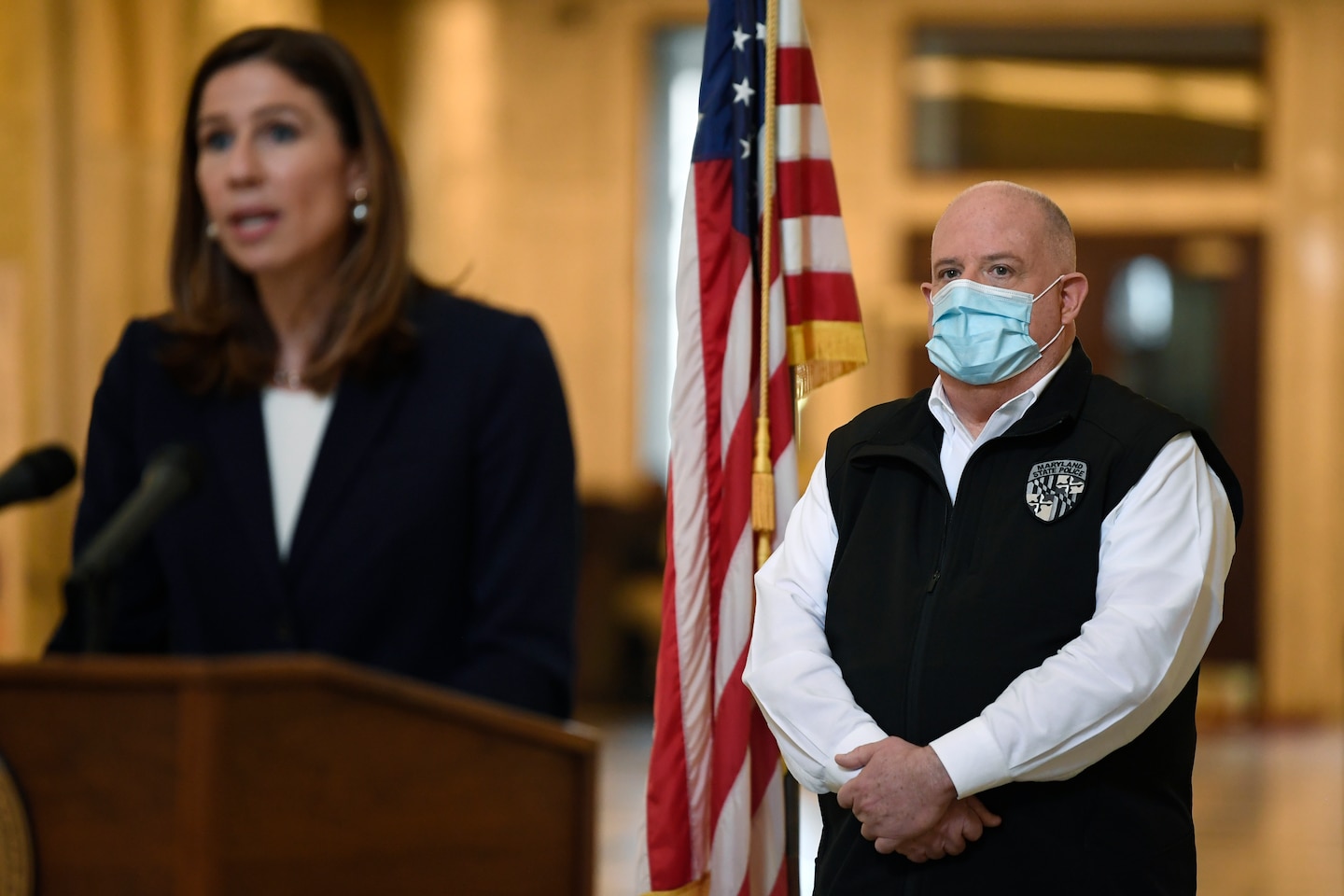

Maryland Labor Secretary Tiffany Robinson recently told a legislative panel that the fund has about $600 million — about the same amount the state has spent in the past three months. To replenish the fund, Robinson said businesses are likely to have to pay more in unemployment taxes. The state is looking at borrowing as much as $1.9 billion from the U.S. Department of Labor in coming weeks.

Robinson’s agency had been under fire for months for the failed rollout of its new unemployment benefits claims system, which left frustrated residents unable to file for benefits and waiting weeks — sometimes months — for checks. About four percent of claimants still have not received their full benefits.

Fry Hester said that the state has made considerable progress in spreading the word about the work-sharing program but that there is room for expanding it to more companies and workers. She has written opinion pieces, participated in webinars with small businesses and sent Robinson a letter — written with state Sen. Jim Rosapepe (D-Prince George’s) — recommending ways to increase eligibility for participation in the work-sharing program.

Under current rules, employers can participate if they reduce employees’ hours by 20 to 50 percent. In their letter, Fry Hester and Rosapepe suggest expanding that window to cover reductions in hours between 10 and 60 percent, a range allowed under federal guidelines.

Fry Hester also recommended moving applications online, hiring more staffers to support the program and marketing it to small businesses. Moore said the state has made most of the changes. An adjustment to the eligibility criteria, he said, would require an executive order from Gov. Larry Hogan (R).

Hoping to expand the program nationally, U.S. Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md) has introduced legislation to provide federal grants to businesses that participate in work sharing. The money would help cover some of the costs of reopening.

In 33 years of owning a business, Steve Green of High Mountain Sports in Garrett County, Md., had never laid off anyone. Doing so at the start of the pandemic, he said, was “one of the most difficult things in my life.”

Fry Hester invited him to participate in a webinar about the work-sharing program a couple of months ago. Green said he filed an online application before the webinar ended. Once approved, Green brought all 12 of his full-time employees back at 50 percent of their hours.

“When I laid people off, I was worried I was going to lose some really good employees,” he said. “It became a really good plan to be on.”

Charles Wetherington, president of a medical supplies manufacturer in Anne Arundel County, said he has been talking up the program since his application was approved in late April.

Wetherington, who serves on Hogan’s Workforce Development Board, said he had been considering offering furloughs to about eight of his 42 employees at BTE Technologies. The program allowed him to avoid that step, he said. Instead, he reduced their hours from 40 to 30 per week.

“I’ve been spreading the word like crazy,” he said. “It’s a great program, and for us, very timely.”

This story has been updated to include information about Sen. Chris Van Hollen’s legislation and problems with Maryland’s unemployment benefits system during the pandemic.