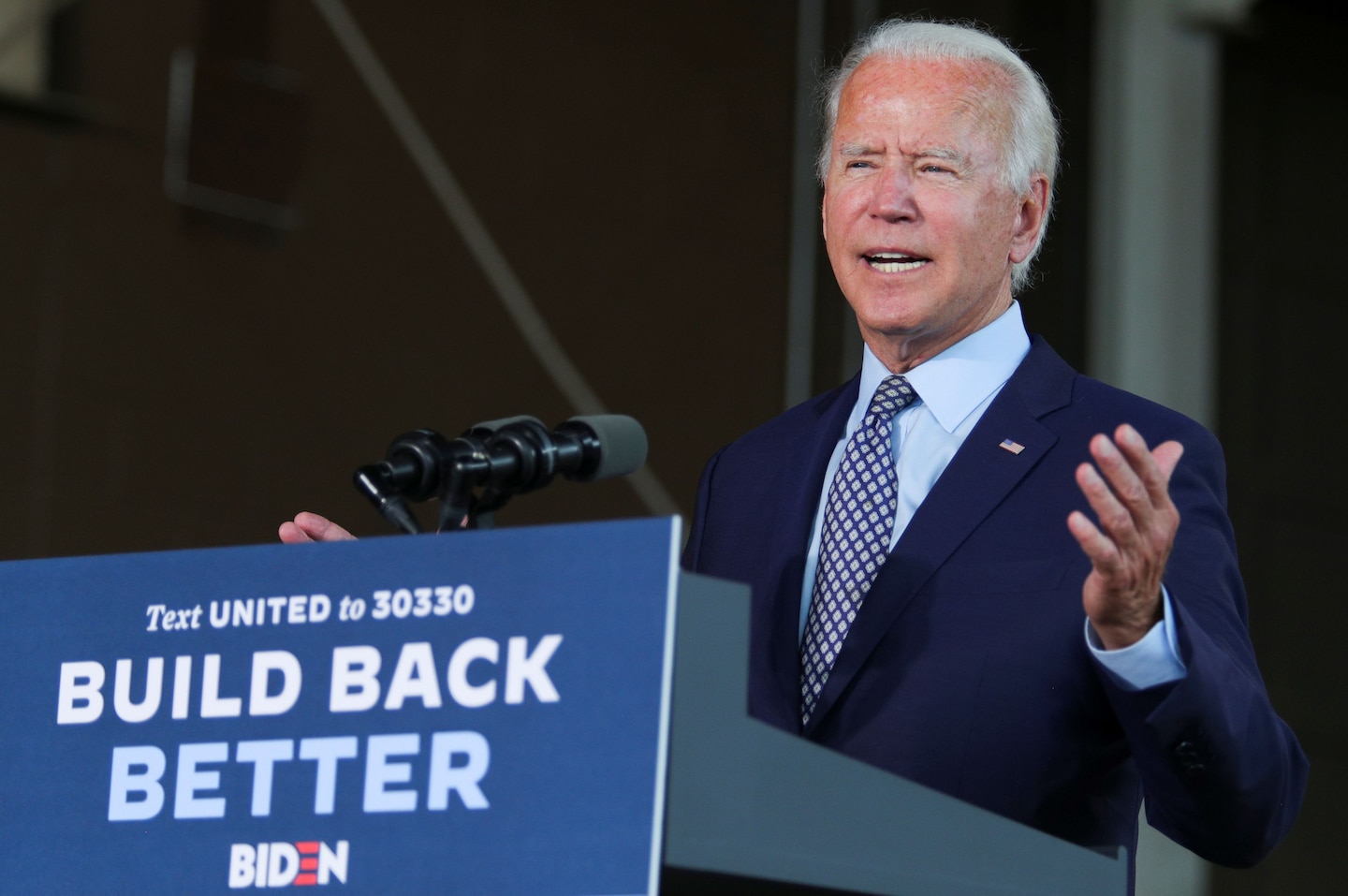

Biden finds a better way to do ‘America First’

First and most important is what the plan does not do. It is not a mercantilist call for tariffs and trade wars, hallmarks of the Trump presidency. These Trump policies have failed by any measure. The evidence is so clear that when Biden released a fiery ad saying Trump “lost” the trade war with China, Politifact’s only quibble with that claim was it should have been present tense “losing.” The group pointed to the following studies from 2019: a Federal Reserve report that determined the tariffs “have not boosted manufacturing employment or output, even as they increased producer prices”; a Moody’s analysis finding that the trade war had cost 300,000 U.S. jobs; and a Federal Reserve study assessing the cost of these tariffs to the average American household at about $800 per year, erasing the benefits of the Trump tax cut. Oxford Economics estimated the trade war shaved 0.3 percent off U.S. gross domestic product growth last year.

The Biden plan’s boldest idea is to massively ramp up investment in research and development. Biden proposes raising spending by $300 billion over four years, which represents a 60 percent increase over 2018 spending. If enacted, this would reverse the steady decline in federal investment in science and technology since its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s. (To get to those levels would still require hundreds of billions more.) Those investments led to the personal computer, the Internet, the Global Positioning System and a host of other technologies that have transformed the economy. More recently, it is worth remembering, an Energy Department loan of $465 million is what enabled Tesla to establish itself and experiment with electric cars. The Biden plan proposes investments in 5G technology, electric cars, lightweight materials and artificial intelligence. Some of this money will be wasted — as also happens to investments from venture capital firms — but all you need is for some, like Tesla, to succeed big.

The plan also has a $400 billion “Buy American” component. The theory behind this is sensible. But the danger of this kind of approach is that it can too often become “industrial policy,” with the government trying to revive bygone industries like steel (as Biden wants to do) and favoring firms with the best lobbyists. More generally, the track record of most rich countries in practicing industrial policy has been pretty bad. Experts used to point to Japan as the country that had mastered government-directed investment, except that it turned out that Japan’s best companies all came out of its fiercely competitive private sector. The state-sponsored ones mostly did poorly. (China is different because its biggest advantage is not smart government investments but low wages.)

The best model is not for government to set up or subsidize specific companies or industries, but to let the market know that it will buy certain kinds of innovative products, which then gives the private sector an incentive to produce them. As late as 1962, the U.S. government was responsible for purchasing 100 percent of all semiconductor chips produced in the country, which is what allowed that industry to become viable. Similarly, NASA orders powerfully helped the computer industry in the 1960s. Biden rightly wants to emulate this approach to support today’s breakthrough technologies, though key agencies in the federal government in those days were more efficient and operated with far greater insulation from special interests.

A final caution: “Buy American” has been around for a long time. In fact, it was initiated in 1933, on the last day of Herbert Hoover’s term in office, responding to a “Buy British” plan announced in London. The result of these kinds of moves sent the world into a downward spiral of protectionism and nationalism, impoverishing ordinary people, and creating a dangerous international climate. Let’s keep that history in mind as we implement the next version of Buy American.

Read more: