Who will be our conscience now that John Lewis is gone?

Dawn Porter is the director of the CNN/Magnolia Pictures documentary “John Lewis: Good Trouble.”

When you decide to make a documentary about someone, you fall completely into their lives. For most of 2019, that happened to me; I happily immersed myself into the singular life of John Lewis. I followed him through Georgia, Texas, D.C. and Alabama, trying to capture with a camera the personal side of the man many knew only from a picture of a confrontation with state troopers in Selma in 1965.

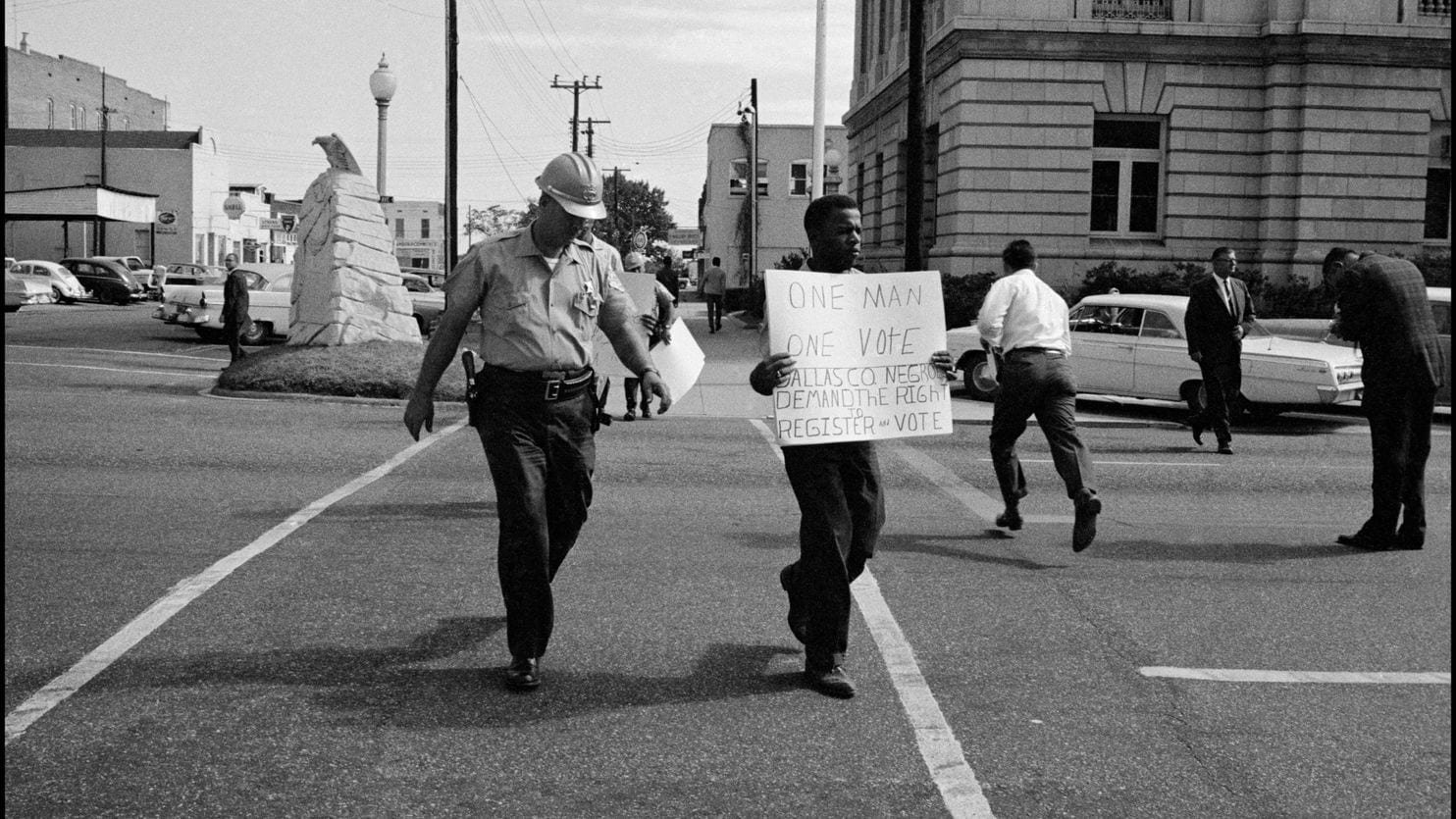

As I sifted through archival footage from the 1960s, I saw countless examples of Lewis walking again and again, with almost preternatural calm, into firestorms of hate. Rewatching some of that footage today, I find it hard to understand why the United States still has so much work to do to live up to the promise of equality.

As I spent time with the congressman, I noticed from the start the reaction he inspired from strangers. Lewis was a living legend to be sure, but he was more than that to people. No matter where he was, people stopped to greet him as though he was an old friend, thanking him for his leadership and all that he had done. Most felt compelled to make sure he knew how meaningful his example had been for them, particularly as racist behavior we naively thought long gone resurfaced in our country.

I felt this myself. With all that he endured, seeing Lewis living a peaceful, purposeful and happy life was a reminder to me that it is okay to hope.

For Lewis, politics was personal; laws could not be separated from their moral underpinnings. So, he challenged America to do better. Lewis was arrested more than 40 times during the civil rights movement and five more times as a member of Congress, where he served as a 17-term Democrat from Georgia. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has often referred to him as the conscience of Congress. How we need a conscience today. Who can speak with the same moral urgency now that he has passed?

I’d first met Lewis years before in D.C., when he spoke to a gathering of public defenders I was profiling for a different film. He thanked the lawyers for their work and reminded them that he and the other civil rights workers would have languished in the brutal jails of the segregated South without their help and the help of their predecessors. Hearing his words, they were able to see themselves perhaps for the first time as the heroes of their own story.

Our paths crossed again when he agreed to an interview for a four-part Netflix documentary series about Bobby Kennedy. He told a story about a rally for Kennedy in Indiana on the night in April 1968 that Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. Lewis urged Kennedy to speak to a waiting crowd in Indianapolis; it was Kennedy who told the largely black audience about King’s death. A couple of short months later Kennedy himself would die, felled also by another hateful assassin. It was then that Lewis said he nearly lost his faith in America.

Last spring, we drove to Troy, Ala., to his family home, situated on land his sharecropper parents purchased for $300. We sat under a shady tree surrounded by his high school classmates and a favorite teacher, drinking lemonade and telling stories. He bowed his head as each of his friends shared memories of segregation: outdated textbooks, inferior buildings, repeated humiliations large and small. They told me that after Lewis left Troy, they would listen for news of him on the radio, worried but terribly proud. He was out marching for all of them, too.

I last saw him in person on Valentine’s Day 2020, when I flew to D.C. to show him the final cut of the film. I brought chocolates (he had a sweet tooth) though I knew his staff would fuss about it. He answered the door to his home, dressed as always in slacks and a bright sweater. As we watched the film together, he kept saying, “It’s so powerful, so powerful,” to which I replied, “Congressman, it’s your life that is powerful.”

These past few months I have watched his final battle from afar, knowing that he would face cancer with his uncommon strength. I learned so much from him these past few years, but the lesson I keep coming back to is this: You do not have to shout to be heard. True power can speak in the quietest voice.

He asked for nothing other than for others to recognize his humanity. He has managed to do something so many of us are struggling with — to never give up on the promise of America. I think often of the last words of the last interview we did. “We shall overcome,” he told me.

I think he’s right. I hope he’s right. I know we must try.

Read more:

Colbert I. King: John Lewis will always be with us

David Greenberg:‘Invictus’ was among John Lewis’s favorite poems. It captures his indomitable spirit.

Michele L. Norris: A running giant passes the baton

The Post’s View: How John Lewis caught the conscience of the nation

Jonathan Capehart: John Lewis practiced what he preached. We are a better nation for it.