Years before players took a knee, Carlos Delgado learned how hard it can be to take a stand in MLB

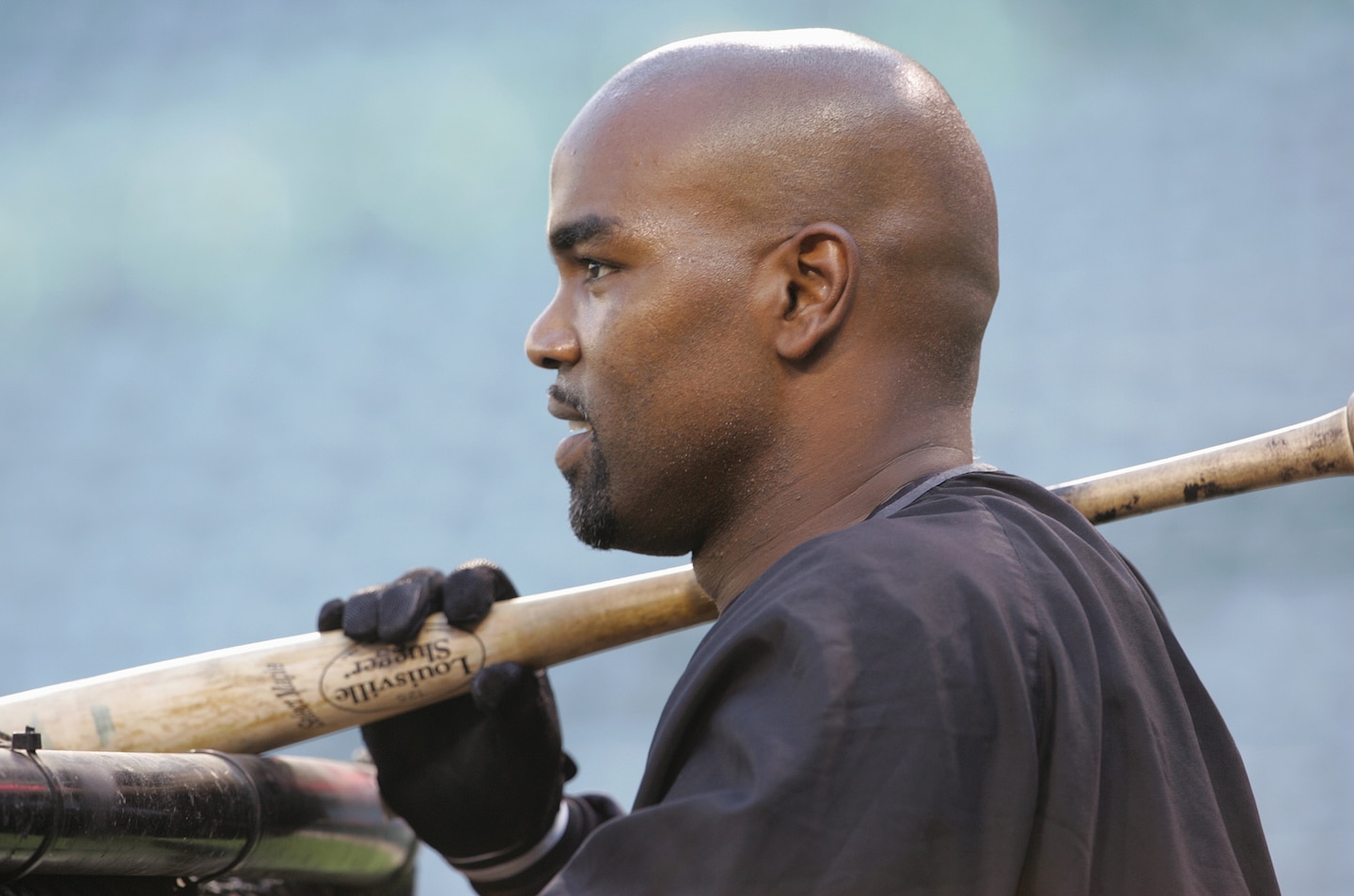

He didn’t let the buttoned-up nostalgia of the game he starred in for nearly a generation in the 1990s and 2000s, when he became one of just six players to hit 30 home runs in 10 consecutive seasons, dampen his desire to disrupt it to call attention to a matter for which it was supposed to be a diversion.

And Delgado didn’t let his first language, Spanish, make him uncomfortable communicating his thoughts to English-language media.

As the Bush administration in 2004 ramped up its war against Iraq, Delgado did what few athletes — and even fewer baseball players and almost no Spanish-speaking ballplayers — did or do: He stood up, he spoke out, and he used his game’s stage to protest for a cause.

As the playing of “God Bless America” during the seventh-inning stretch slowly became custom in the wake of 9/11, Delgado, with Toronto then, began to disappear into the bowels of whatever dugout he was in. He would emerge only after the last bar. “I don’t believe in war,” Delgado explained when asked about his conspicuous disappearance during the song. For a couple of years prior in Puerto Rico, he was involved in protests against the U.S. military installation on the island of Vieques.

“I wanted to demonstrate my dissatisfaction with our clear systemic racism in our country,” Kapler told reporters.

While pro football saw black and white players shut down an all-star game in the 1960s over racial discrimination, and pro basketball players have donned T-shirts sporting political statements and openly protested an owner with bigoted beliefs, and NASCAR just banned the Confederate flag and raced a Black Lives Matter car, Delgado, Maxwell and now Kapler’s players are pretty much the history of histrionic remonstration in baseball for political cause. In a century and a half. Not counting the 60 years or so, of course, when baseball positioned itself as a paragon of prejudice by aligning itself with America’s apartheid system known as Jim Crow by refusing to allow men of color to play its game.

“In baseball, we have a lot less African Americans,” Delgado told me Monday from his home in Dorado, Puerto Rico, just outside San Juan. “Having said that, that does not make an excuse. What’s fair and seeking justice should not be attached to black or white.

“Number two, it seems that baseball is a lot more traditional than other sports,” Delgado said, “and you can see it from their marketing to the entertainment. Baseball lags behind. Players feel like, ‘If I speak out, I’m going to get punished.’ ”

To be sure, Maxwell, who was a catcher for Oakland at the time of his demonstration, found his only work the past two seasons since he knelt playing for the Acereros de Monclova of the Mexican League. He has complained his inability to get back in the big leagues is not coincidental with his political stance.

Delgado played for five years after his protest until he was 37. But unlike Maxwell, he was an established star who garnered MVP votes in three of his last five seasons.

And Delgado is comfortably bilingual.

“If you’ve got 30 to 40 percent Latino players, that’s a lot of mostly Spanish-speaking players that not all of them are completely fluent in English,” Delgado said, “and sometimes they’re looking for their American citizenship and they don’t want to speak out against the establishment.”

Delgado was always certain of his footing. He was an American citizen as a Puerto Rican. His father was a social worker who was a supporter of the Puerto Rican independence movement to break from the United States.

“He was a political target, because in the ‘60s if you were pro-independence in Puerto Rico you used to be targeted by the police and the government,” Delgado said.

“We were aware of a lot of stuff that was going on, but we were also taught that we’re looking for equality,” Delgado said. “My father was like me, a big, dark man. My mother is white, Puerto Rican white. So since I was a little kid, I saw that. But my father was a big influence. They were very fair people. And I know he had his issues with being racially targeted and politically targeted.

“And I was a fan of [Roberto] Clemente,” Delgado reminded.

In 2006, Delgado was presented the Roberto Clemente Award as the baseball player who best exemplifies the humanitarianism of Clemente, the Hall of Fame Puerto Rican outfielder who died in 1972 in a plane crash delivering supplies to victims of an earthquake in Nicaragua.

Delgado’s protest wasn’t easy. What protest is? During a series at Yankee Stadium in July 2004 after the reason for his refusal to join in “God Bless America” was revealed, he said he never heard boos so loud. But the Blue Jays organization supported him. Some of his teammates spoke in his favor; none argued against him.

“I’m not saying this to knock the game,” Delgado said. “That’s the game that I love. I had the opportunity to make a living playing that game. But seeing the other sports are moving a little quicker than baseball . . . this is something they can play a bigger role. I mean, at the end of the day, who doesn’t want justice? Who doesn’t want equality? That’s what I try to teach my kids. That’s the way I try to conduct my life.

“I felt like part of my job other than playing baseball was to look for a better way, look for a better society,” Delgado said. “I wish baseball was a little bit more proactive.”

And if not this season, as the country is roiled by racial reckoning, then when?

Read more from The Post: