After I discovered that my ancestors had enslaved people, I connected with a descendant of those who were enslaved

I didn’t know much about my Dutch ancestry when I was growing up in New York’s Hudson Valley in the 1960s and ’70s. I thought of myself as Italian. My father was the second son of an immigrant named Pasquale Bruno, who had made his way to New York as a teenager from southern Italy’s impoverished Calabria region. Our holidays were feasts of pasta, meatballs and eggplant Parmesan. The smell of tomato sauce simmering on a Sunday is all I need to feel at home.

But of course there is also my mother’s side. Her maiden name is Van Valkenburg. All I really knew about her ancestors was that they had helped settle New Netherland, as New York state and the surrounding territory was called in the 1600s. “Think Rip Van Winkle,” I would tell people about that part of my heritage. The Dutch side, I thought, was more white-bread plain. Yet I did wonder about those Dutch, and when the boom in companies like Ancestry turned millions of Americans into amateur genealogists, I joined the trend and started researching. I imagined I’d find a string of farmers and housewives and shopkeepers and laborers, living modest, quiet lives.

Then one day, scrolling through the Ancestry website, I came upon the 1796 last will and testament of one Isaac Collier, born in 1725 in a place called Loonenburg, which is today named Athens. That’s my hometown. And Collier is my grandmother’s maiden name. Isaac was my five-times-great-grandfather.

Isaac was thinking about his legacy. In his will, the 70-year-old carefully divided his land, working out in precise detail where his property lines extended and to which of his five surviving sons each parcel went. Then he got to other items: to his son Joel, “one other Feather Bed, one Negro Boy named Will and my sorrel mare and sorrel stallion, one wagon and harrow.” To his granddaughter Christina Spoor went a “negro wench named Marie.”

“The remains of my negro slaves male and female,” I read, were to be “equally divided” among his remaining sons and one grandson, “share and share alike.”

I sat very still. This will, written in a beautiful, sweeping script, with elegant phrases like “whenever it shall please the Almighty to take me to himself,” hit me with a gut punch. Here was a man blithely imagining his reception into heaven while painstakingly leaving this permanent record of sin.

Here, in the branches of my family tree, was incontrovertible evidence that my Dutch ancestors weren’t just innocent farmers. That I was the descendant of people who enslaved others. How could this be? Growing up in the North, I’d rarely thought about slavery, and the civil rights struggles of the 1960s seemed as distant as the moon landing. But suddenly, slavery was as real as the rolling hills beside the Hudson River that flowed past my parents’ home. Suddenly, my sense of Northern disengagement from our country’s original sin was snapped away.

I needed to unearth the story of slavery in New York, a memory that seems to have been smoothed over like so many flat tombstones, polished and whitewashed until they are impossible to read. I remembered something the author Toni Morrison had once said in a radio interview: “If you are really alert, then you see the life that exists beyond the life that is on top.” I went looking for that life beneath.

A barn under reconstruction at the Bronck House in Coxsackie, N.Y. The original house on the grounds was built in 1663 for one of the area’s first families.

The author, who grew up in Athens, N.Y.

LEFT: A barn under reconstruction at the Bronck House in Coxsackie, N.Y. The original house on the grounds was built in 1663 for one of the area’s first families. RIGHT: The author, who grew up in Athens, N.Y.

As a child, I’d learned nothing about New York state’s history of slavery. I didn’t even know that there had been enslaved people in the North. We weren’t like those racist Southerners, or so we thought.

In elementary school, we took the requisite trips to places like the Bronck House in Coxsackie, built in 1663 for one of the region’s first families, from whom the Bronx gets its name. Low beams, enormous fireplaces, historians wearing Colonial dress. No one mentioned slavery other than in relation to the Civil War, a war that happened elsewhere and much later in history. Northern slavery wasn’t part of our school lessons. Only since about 2016 has New York state slavery been listed as a small part of the seventh-grade social studies curriculum, says Dennis Maika, education director of the New Netherland Institute and a former high school teacher, but individual schools can decide what to include.

High school classes have the same limits. Courtney Grey, who teaches high school social studies in Lagrangeville, just east of the Hudson Valley, last year created an elective course called “Black America: 400 Years of African-American Contributions,” for juniors and seniors. She devoted a week to the subject of New York slavery, and her students’ reactions were, “Why didn’t I know that?” she says.

It was my question, too. Not having this knowledge had allowed me to grow up detached from questions of race, from the legacy of slavery, and to think of its consequences as something irrelevant to me. But now I was part of it, and it was part of me. And the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests and our country’s ongoing struggles with race have taken on a completely new weight and meaning.

Now that I had a glimpse of this history, I wanted to know: Who were the people my family had enslaved? And could I find a descendant of theirs today?

Some scholars believe that Northern slavery was deliberately whitewashed from the history books. Leslie M. Harris, a professor of history at Northwestern University and author of “In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863,” says that the idea of a free North that helped end slavery is “one of the most powerful elements of our culture.” Adding in Northern slavery “complicates what is otherwise a simple, heroic story.”

But slavery was not only a powerful institution in New York; it lasted for nearly 200 years there. Not long after colonizing New Netherland in the 1600s, Dutch settlers, needing to fill a labor shortage, began buying enslaved people from traders with the Dutch West India Company. (The Dutch also tried to enslave the Native Americans who lived nearby, but many of them escaped. They also tried using indentured servants imported from Europe, but those people also tended to die very young or run off, according to Historic Hudson Valley, an organization with a website dedicated in part to teaching about slavery in New York. Of course, it was impossible for Africans to blend in and escape in the same way.)

New York was one of the last Northern states to outlaw slavery. But instead of a sudden explosion of freedom, the state passed the Gradual Emancipation Act of 1799, which slow-rolled freedom over nearly 30 years. It was a compromise measure designed to placate the Dutch farmers reluctant to give up their property.

My roots in the mid-Hudson Valley run deep, and now I suspected that if one family in my tree enslaved people, there had to be others. So I dove in. The more I dug, the more enslavers I found in wills and census records: Hallenbeck, Vosburgh, Van Petten, Van Vechten, Conine, Brandow, Houghtaling and, yes, Bronck.

I also realized that I was not alone. Jonathan Palmer, archivist at the Vedder Research Library in Coxsackie, says that anyone with deep-enough Dutch roots in the region will eventually find enslavers. “For them to have that moment when they confront that is special for me as an archivist,” he says, “for them to stare at a mirror and realize this was the side they were on.” Often, amateur genealogists don’t follow up on that information, he says, possibly because going further is a “huge task.” But I became almost obsessed with seeing what else I could dig up.

One remarkable document from this history is the Coxsackie Record of Free-Born Slaves, maintained from 1799 to 1827, in which enslavers registered the births of their enslaved people’s technically freeborn babies. Local genealogist Sylvia Hasenkopf, whom I hired to dig deeper into my history, brought it to my attention. Of the 46 enslavers on that record, at least 17 belong to me, most as direct ancestors.

Now that I had a glimpse of this history — which surprised my mother and siblings as much as me — I wanted to know: Who were the people my family had enslaved? What had become of them? And could I find a descendant of theirs today?

Eleanor at Mary Vanderzee’s grave. (Although the headstone says Mary was born in 1801, her death certificate indicates that she was born in 1802.)

Eleanor at Mary Vanderzee’s grave. (Although the headstone says Mary was born in 1801, her death certificate indicates that she was born in 1802.) One name on the record that Hasenkopf found jumped out immediately: Casper Collier, Isaac’s fourth son and my four times great-grandfather. In the 1800 federal Census, Casper listed six enslaved people. Who they were is almost impossible to know, since early census records required the full names only of heads of households; everyone else, free and enslaved, was simply a check mark.

But Casper’s name also appears in the Coxsackie Record. In 1802, a girl named Sawr was born to a woman named Nan. He officially “abandoned” that infant, a legal maneuver that allowed enslavers to receive some compensation for raising children they technically did not own. The Overseers of the Poor, an early version of welfare superintendents, would pay enslavers for the care of babies born to enslaved women. But rather than receiving complete freedom, the children born after 1799 would be indentured at the age of 7 — bought and sold in a manner almost identical to slavery — until they were young adults.

According to an affidavit that Nan (also called Nancy) filed in 1823 to determine her daughter’s future, Nan states that Casper sold her off soon after the birth of Sawr (later renamed Sarah). Nan was sold and resold over the next 10 years, taking Sarah with her — until one of Nan’s new enslavers decided that he didn’t want the child. Nancy’s husband, who bought her freedom in 1812, tried to find a place for Sarah around the same time. Sarah then bounced around from “owner” to “owner.”

I may never learn what happened to Sarah, but her story gave me a glimpse into the twilight period of slavery’s lethargic end in New York. What it showed is that for people like Nancy — born enslaved and not emancipated until her husband bought her freedom — and Sarah — born free but shuttled from place to place — the official end of slavery meant next to nothing for a long time.

I dove back into my Ancestry account and built out a family tree based on Nancy, whose surname was Jackson. Hasenkopf found a Nancy Jackson of the right age, living near Albany, where Nancy was living, according to her affidavit. In this household and right next door were other people named Jackson, who were a generation younger, the right age to be her children. I kept plugging these names into an Ancestry tree, Jackson after Jackson, until I came to the contemporary family tree of an African American woman living in the Hudson Valley.

I tracked her down and got her on the phone, hoping we could connect and start to search together. She was polite but distant. She didn’t say no, but it became clear to me that she was less interested in getting to know a person potentially connected to her ancestors’ enslavers than I had hoped. At the same time, Hasenkopf warned me that all my quasi-creepy research was probably for naught. “I looked at the family tree you created online and frankly don’t think some of your assumptions are accurate,” she wrote by email. I was back to square one.

Then, through a group called Coming to the Table, which, among other goals, seeks to bring together the descendants of enslaved people and their enslavers, I learned about a Facebook group called I’ve Traced My Enslaved Ancestors and Their Owners. I posted a note, describing my enslaving ancestors and asking if anyone had a connection to the Hudson Valley in New York. Within 24 hours, I got a response: “I have ancestors who were enslaved in Coxsackie/New Baltimore.” Boom. The writer had named the town right next to my hometown. We arranged to talk on the phone.

I was a little nervous about reaching out once again to someone descended from people my people almost certainly enslaved. In that first talk, though, Eleanor Mire and I settled easily into a conversation about family histories. A retired construction engineer, Eleanor, now 69, grew up outside Boston hearing from her grandmother that though some of her ancestors had lived in the Hudson Valley, there had never been an enslaved person in that branch of the family. “She must have known that there had been a slave,” she told me. Why had she denied it? I asked. “That was my grandmother all over,” she responded. “Pride.”

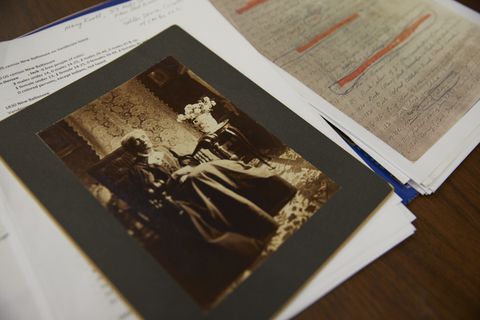

Mary Vanderzee, whose parents were enslaved. “I see my grandmother in her face,” says Eleanor, who is descended from Mary’s son Thomas.

Mary Vanderzee, whose parents were enslaved. “I see my grandmother in her face,” says Eleanor, who is descended from Mary’s son Thomas. But Eleanor came across the truth when the wife of a distant cousin started doing research and found a wealth of material. Suddenly she was building a family tree and digging into her Hudson Valley roots, all enslaved people: Vanderzee, Van Bergen, Egberts, names that her African American ancestors had taken from their white enslavers, and often the very same names populating my own family tree.

It was strange and sad, I said to her, that my ancestors were involved in the enslavement of hers. She cut me off. “You had nothing to do with it,” she said. “To me, if you perpetuate the myth” that slavery was not so bad, “you should feel bad.” Otherwise, “there’s nothing you could have done.”

Over the next few months, Eleanor and I exchanged hundreds of messages with details we uncovered about fuzzy census records, homes, cemeteries, church records and death certificates. We kept coming back to one person: Mary Egberts Vanderzee.

As far as we can figure out, Mary was one of the babies listed on the Coxsackie Record. (The names of the mothers and babies sometimes changed.) Her parents were enslaved people named Cesar Egberts and Rebecca Dunbar. Born in 1802, Mary was sent to the Houghtaling family as a child, where she was raised as a combination of servant and companion to a white child, a common practice. But Mary’s childhood didn’t last long. Unmarried and still living with the Houghtalings, she gave birth to her first baby at 13 and had three more while she was in her teens, Eleanor told me.

Eleanor is descended from Mary’s son Thomas, who eventually took the name of her second husband, John Vanderzee. Mary’s first husband, John Van Bergen, whom she married after giving birth to her four children, seemed to have died young. She married Vanderzee on Dec. 25, 1838. Eleanor wondered: Who was the father of Mary’s first babies? She decided to get her DNA tested — and turned up matches with several people named Houghtaling. Ancestry told her that the closest are fifth to eighth cousins, including one person with the profile name Redhead1847, descended from a Peter Houghtaling born in 1759. Eleanor sent that person an email but never heard back.

But she had other evidence of a genetic link to the Houghtalings. “My grandmother said her grandfather was fair-skinned and blue-eyed,” Eleanor told me. That grandfather would have been Mary’s baby Thomas. It seems that a member of the Houghtaling family most likely raped Mary.

Here’s where Eleanor and I become linked descendants. I’m a Houghtaling too, descended from a woman named Catrina Houghtaling, born in 1680. She was the second daughter of Mathys Conraed Houghtaling, who as a teenager in 1655 came from the Netherlands to New Amsterdam, the 17th-century Dutch settlement in what is now Manhattan. But while I can build out my own tree with great detail, Mary Vanderzee’s life is shrouded in mystery.

Eleanor, the author and archivist Jonathan Palmer at the Vedder Research Library, which has records such as a list of children born to enslaved people.

Palmer says that anyone with deep-enough Dutch roots in New York’s Hudson Valley region will eventually find enslavers in their family history.

LEFT: Eleanor, the author and archivist Jonathan Palmer at the Vedder Research Library, which has records such as a list of children born to enslaved people. RIGHT: Palmer says that anyone with deep-enough Dutch roots in New York’s Hudson Valley region will eventually find enslavers in their family history.

Eleanor and I talked and texted, sending snippets of facts, newspaper clippings, photographs. When she told me she’d be visiting Washington in August, we arranged to meet. I was nervous, but we hit it off instantly, two near-strangers on a shared mission.

I asked if she’d be interested in visiting Coxsackie, and she agreed immediately. One morning in September, we made our way to the Vedder Research Library on the grounds of the Bronck Museum, a repository of archives tracing the history of the area back to the 1600s. In the thick file on the African American Vanderzee family, we found an article, written around 1902 for a bicentennial book celebrating the hamlet of New Baltimore, about Mary Vanderzee as she turned 100. “She was brought up as playmate and companion to the children and children’s children,” the writer notes. “Her life is a romance,” and she never tired of telling guests about soldiers passing by her farm during the War of 1812. Black Mary, as she was called, lived “a long and useful life filled with service.”

Accompanying the article was a photograph of her taken in her daughter’s home. She is rail thin and leaning slightly forward in her oak Morris chair. She is unsmiling, lips pursed. Her eyes look straight forward, almost suspiciously. Her skin is dark, her hair is white, her nose is long and narrow, and her hands are crossed delicately at the wrist.

Eleanor and I share a peculiar thread of the American story, one that starts with white privilege, and another that starts with black oppression. But it doesn’t end there.

It wasn’t the first time Eleanor had seen the photo — her cousin had shown it to her years ago. She held it up. “My mother would say that’s a Vanderzee face,” she said. “I see my grandmother in her face.”

The morning passed as we stared at photographs, reviewed Overseers of the Poor records, and tried to make out, from ancient maps, who had owned what land. At one point, Eleanor pulled an index card from a file cabinet. The record showed the Christmas Day marriage in 1838 of Mary Egberts and John Vanderzee. “My family is unbelievable,” she finally said. “And it’s all from my grandmother’s side — who never told us anything.”

We drove to Riverside Cemetery. Founded in 1873, it’s segregated by custom, with African American graves clustered to one side. Eleanor remembered that when she visited many years ago, she’d had no idea where her ancestors lay, yet she’d found Mary’s gravesite almost immediately. Now we drove directly to the spot. The granite stone rested in the dappled shade, with the name Vanderzee carved on the broad side. On the narrow side was carved “Mary Vanderzee, 1801-1907.” Nearby were Van Bergens and Van Slykes and Brandows, all black people who had taken the Dutch names of their enslavers. Many gravesites were decorated with medallions to honor the men who had served with the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War.

As we drove out of the cemetery, I deliberately detoured past the stone of Isaac and Casper Collier. I pointed it out, but we didn’t stop. Today was not for the enslavers.

Eleanor and I fell into an effortless friendship. Race comes up from time to time. She told me, for example, about an ancestor who was given land in Iowa as payment for his father’s service in the War of 1812, only to have his family driven out of the land by racist attacks. But our main and mutual obsession is about filling in the blanks of this whitewashed history. Why were the stories connecting the Dutch immigrants and the people they enslaved not told?

We share a peculiar thread of the American story, one of us from a place that starts with white privilege tempered with immigrant struggles, and another that starts with black oppression. But it doesn’t end there. Eleanor’s family is packed with people who have touched history, including James Van Der Zee, the famous Harlem Renaissance photographer, and an ancestor who was involved in the Underground Railroad. Mine is more modest. We have been teachers and factory workers and many, many farmers.

I don’t know what to say about the past. My Dutch ancestors helped perpetuate an evil that lasts to this day. Even in the context of more than 200 years and five generations past and a time when racism was the norm, what they did was wrong. What I do know is that I can no longer consider racism from afar and feel that it has nothing to do with me. I wish I could take only pride in the fact that my family is older than America, that my ancestors fought in the American Revolution, the War of 1812 and the Civil War. But now my pride is tainted, and my sense of myself and who I am has shifted perceptibly.

And yet Eleanor — who is unsentimental and smart and funny about everything — has shown me that there is a way to look into both our families’ histories and see and embrace the truth, but not let it forever weigh us down. In the end, I don’t know if this story is about atonement or reconciliation. Or maybe it’s more of a reckoning. Eleanor said in one of our talks, “People don’t understand. Slavery is a thread going through the generations. It has affected every generation.” She and I are not done. But we’ve started with this.

Debra Bruno is a writer in Washington.

Design by Christian Font.