Meatpacking workers file lawsuit against OSHA, accusing agency of failing to keep them safe

Maid-Rite Specialty Foods did not respond to multiple emails and telephone requests for comment.

Representatives for OSHA and the Labor Department did not respond to a request for comment. But OSHA officials have said that they believe its existing regulations, along with the updated guidelines put out during the pandemic, are sufficient to keep workers safe.

The lawsuit is one of several legal challenges seeking to compel OSHA, as well as private businesses, to act more forcefully to uphold protections around worker safety.

The lawsuit, filed in federal district court in Pennsylvania, is based on a complaint that attorneys working on behalf of the workers filed with OSHA in May.

The complaint accused Maid-Rite of failing to provide adequate protective gear or social distancing on the processing lines.

The Maid-Rite workers also said in the complaint that the company did not handle ill employees in a safe manner, failing to separate sick employees and to inform all of those who worked closely with them when there were infections. The complaint also said the company gave workers incentives to work while sick, by offering bonuses to those who didn’t miss days.

The lawsuit claims that OSHA failed to adequately respond to that complaint, as it is required to do.

Two of the attorneys who filed the lawsuit, David Muraskin, at the nonprofit Public Justice, and David Seligman, executive director of the worker legal group Towards Justice, say that the case will serve as another test of whether OSHA can be held accountable in court.

“This is because of the federal government’s failure to step in here,” Seligman said of the lawsuit. “We hope that the lawsuit spurs OSHA into action for these workers. Every day they go to work, they’re in imminent danger. If the virus were to enter the facility, there’s every reason to believe that it could cause death.”

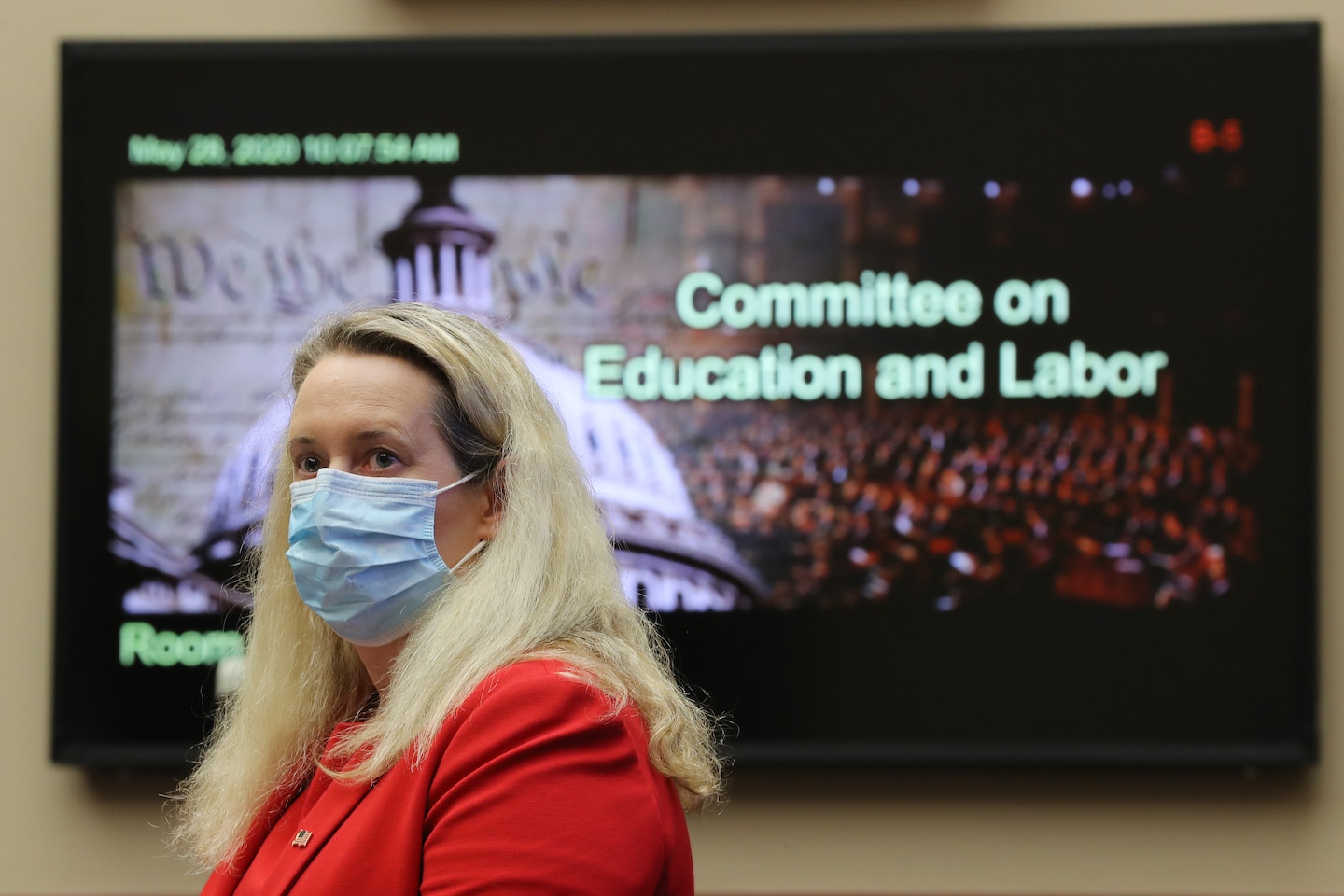

Back in May, Loren Sweatt, the principal deputy assistant secretary of labor for OSHA, testified before Congress that the agency received 4,268 coronavirus-related complaints as of May 21, of which nearly 3,000 had already been closed. She said that worker safety has been the agency’s “top priority” during the pandemic and that it will increase in-person inspections and enforcement of workplace coronavirus case reporting as states reopen.

Yet despite the complaints, the federal agency had issued only one citation as of the end of May. And OSHA has declined so far to issue emergency regulations that would force national safety standards for workplaces dealing with the virus, the kind that companies must adhere to under threat of citations and penalties.

While OSHA hasn’t responded to a request for comment on this lawsuit, the agency did respond to the workers complaint from May, according to supporting documents included in the lawsuit.

A day after OSHA received the original complaint on behalf of Maid-Rite Specialty Foods workers, Mark Stelmack, an area director for OSHA in its Wilkes-Barre office, wrote to Maid-Rite outlining the allegations it put forth, according to the lawsuit.

Stelmack requested that Maid-Rite Specialty Foods immediately investigate the concerns and “make any necessary corrections or modifications” but noted that “OSHA does not intend to conduct an on-site inspection in response to the subject complaint at this time,” the lawsuit stated.

The company would be required to document any findings, Stelmack said, and he also asked for a long list of questions to be answered — about whether there were infections at the plant and what kind of safety protocols were in place for workers, according to the lawsuit.

Stelmack wrote that OSHA was aware that global demand for safety gear had limited the availability of some protective equipment, noting that “if this situation has prevented you from furnishing protective equipment to your employees, you should provide that documentation.”

An OSHA official told attorneys for the workers that Maid-Rite had sent an extensive response to the inquiry, but the agency declined to share the response with the lawyers, according to documents filed in the lawsuit.

The workers’ attorneys said in the lawsuit that coronavirus safety hazards continued to persist at the company’s plant through June, and they documented the concern in three follow-up letters to OSHA.

OSHA informed the attorneys by phone that it was in the process of conducting an inspection of the facility, the lawyers said, but the attorneys wrote that they were unable to get more information about it, according to the lawsuit. The review is still open, according to OSHA’s website.

The lawsuit uses what the attorneys on the case say is a novel legal argument, by citing part of the 1970 law that created the agency, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, that they say allows workers to bring legal actions against the secretary of the Labor Department to force OSHA into action.

The provision is rare among the charters for public agencies, whose regulatory decisions and purview typically offer limited avenues for private legal cases, the attorneys said.

“Regardless of the legal outcome, we hope that workers see that people are willing to stand with them and fight with them, and they can use that as mechanism to organize and know people have their back,” Muraskin said.

The three workers are named anonymously in the lawsuit as Jane Doe I, II and III — a provision necessary to protect them from retaliation, their attorneys argue. A judge will rule whether the plaintiffs can proceed using the pseudonyms.

The court records filed in the case include signed statements from each of the workers, in English and Spanish, that detail what they say was a lack of proper safety protocol at the facility.

“Since the complaint was filed with OSHA, almost nothing has changed at Maid-Rite,” each of the statements say.

OSHA has been harshly criticized by workers, labor advocates and former agency officials for near-absent enforcement of safety issues at workplaces during the coronavirus pandemic.

Meatpacking facilities have been one of the country’s largest sources of infections, according to a Washington Post analysis from May. More than 11,000 infections were tied to three of the country’s biggest meat processors alone: Tyson Foods, Smithfield Foods and JBS.

The AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest labor federation, sued OSHA in May, seeking to force the agency to issue stronger safety regulations for the novel coronavirus, but that lawsuit was dismissed in June. Later that month in a separate case, a judge dismissed a case that had been brought against Smithfield Foods, saying that OSHA, not the courts, were the appropriate avenue for oversight.