One home, a lifetime of impact

In 1936, Tai Christensen’s great-grandmother, a housekeeper and widow in North Carolina with four sons, saved up $500 and bought a house at age 35. That decision, which changed the trajectory of her family’s finances for generations to come, wasn’t easy for a black woman facing racist housing policies. Mary Pherribo and her late husband, George Pherribo, were both born to parents who had been enslaved.

Mary Pherribo had been inspired by her late husband’s grandfather, Henderson Faribault, who became a chef upon his emancipation from slavery, bought a 50-acre property and left each of his eight children a house upon his death in 1901, Christensen said.

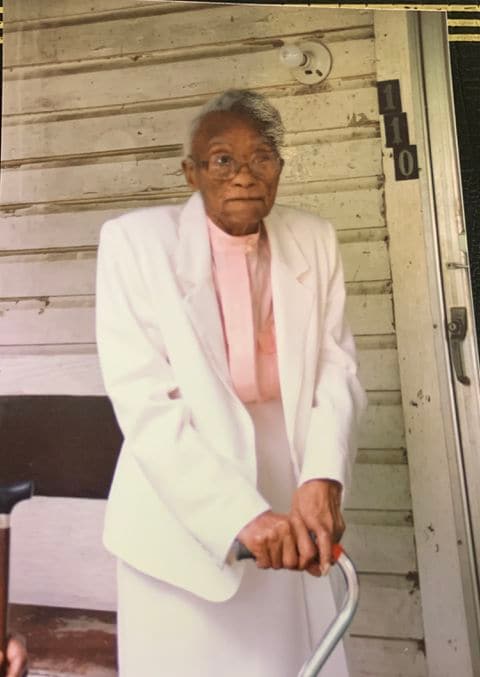

Mary Pherribo’s decision to buy a home in 1936 changed the trajectory of her family’s finances for generations. (Courtesy of Tai Christensen)

Mary Pherribo’s decision to buy a home in 1936 changed the trajectory of her family’s finances for generations. (Courtesy of Tai Christensen) “The guts it took for them to make that choice was amazing,” says Christensen, director of governmental affairs at CBC Mortgage Agency, a national housing finance agency based in South Jordan, Utah, that provides down payment assistance. “It’s proof that you can change the entire line of your family’s story. My father and my uncle own multiple properties and pretty much everyone in my family owns a home and has gone to college because of her decision.”

Unfortunately, that pattern of homeownership and generational wealth building is broken for many black families. In the first quarter of 2020, 44 percent of black families owned their home, compared with 73.7 percent of white families, according to the Census Bureau. The gap is wider in some cities, with just 25 percent of black families owning a home in Minneapolis compared with 76 percent of whites, which is the widest gap in U.S. cities with more than 1 million residents, a study by Redfin real estate brokerage found. In D.C., 51 percent of black households are homeowners, the highest rate in the country, but far lower than the 70 percent of white households that are homeowners.

And even if they’re able to buy a property, black homeowners often face another burden — higher tax assessments, according to an analysis by economists Troup Howard and Carlos Avenancio-León. The research from the University of Utah and Indiana University found that black families pay 13 percent more in property taxes than a white family in a similar home.

[Black families pay significantly higher property taxes than white families, new analysis shows]

“The homeownership gap between blacks and whites is larger today than it was in 1934, which is when the Federal Housing Administration [FHA] was established,” says Donnell Williams, president of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, a Lanham, Md.-based organization formed in 1947 to promote equal housing. “Half of all blacks born between 1956 and 1965 were homeowners by the age of 50, but blacks born from 1966 to 1976 have a homeownership rate of just 40 percent. If trends continue, black millennials may not even reach a homeownership rate of 40 percent by the time they turn 50.”

Causes of the gap

Discriminatory housing policies were outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968 but their effects still linger.

The racist housing policy of redlining assigned grade levels and color codes to neighborhoods to indicate local lenders’ perceived credit risk based in large part on the residents’ race and ethnicity, and it was outlawed in the 1960s. Urban areas with a large share of black families were typically redlined, which made it nearly impossible to qualify for a mortgage. A recent study by Redfin found that the typical home in a redlined neighborhood gained $212,023 or 52 percent less than one in a “greenlined” neighborhood over the past 40 years. Today, black homeowners are five times as likely to own in a formerly redlined neighborhood than a greenlined one, according to Redfin’s study.

“This equates to homes that are worth less, have less equity and are in neighborhoods deemed less desirable due to the lingering effects of redlining,” says Christensen.

The ongoing impact of redlining is illustrated by the disparity in home values between Montgomery County and Prince George’s County in suburban Maryland, says Hazel Shakur, a real estate agent with Redfin in Prince George’s County.

Recently, a single-family “home in Montgomery County sold for $465,000, while a similar home in Prince George’s County sold for $370,000,” says Shakur. “What could account for a $95,000 difference? It really boils down to the lack of amenities and poor school rankings in Prince George’s County. The lack of investment in Prince George’s County is a lingering impact of redlining.”

[The ‘heartbreaking’ decrease in black homeownership]

Shakur says the recession and housing crisis hit harder in Prince George’s, where 83 percent of the population is black or Latino, compared with Montgomery, which is 60 percent white.

This Bowie, Md., home recently sold for $113,000 less than a similar home in Silver Spring, Md., an indication of the lack of investment in Prince George’s County compared with neighboring Montgomery County.

This northern Silver Spring home recently sold for $463,000.

The lingering impact of redlining may be one reason this home in Glenn Dale, Md., in Prince George’s County sold for $121,000 less than a similar home in Montgomery County.

Built in 1995, this Germantown, Md., home in Montgomery County recently sold for $581,000.

TOP LEFT: This Bowie, Md., home recently sold for $113,000 less than a similar home in Silver Spring, Md., an indication of the lack of investment in Prince George’s County compared with neighboring Montgomery County. TOP RIGHT: This northern Silver Spring home recently sold for $463,000. BOTTOM LEFT: The lingering impact of redlining may be one reason this home in Glenn Dale, Md., in Prince George’s County sold for $121,000 less than a similar home in Montgomery County. BOTTOM RIGHT: Built in 1995, this Germantown, Md., home in Montgomery County recently sold for $581,000.

“Blacks ended up in Prince George’s County because they couldn’t always buy in other places because of redlining,” says Shakur.

A broad variety of covenants and policies, including redlining of commercial loans, has led to the gap in home values between the two suburban Maryland counties, says Andrew Fellows, faculty research specialist at the University of Maryland and former mayor of College Park, Md.

“In practice, many of the covenants that excluded blacks from some suburban developments were slow to change even after the Fair Housing Act,” says Fellows. “And banks were slow to make commercial loans, which means that Prince George’s County continues to lag in retail development today. That lack of development, which is broadly related to redlining, keeps home values lower in the county.” Fellows says that Prince George’s County became a majority African American county in the 1980s in part because black professionals left D.C. to escape the school system.

Disparities in homeownership

LEFT: RIGHT: Disparities in homeownership

Housing discrimination prevented blacks from owning homes for more than a century, which continues to affect purchasing power today, says Sheharyar Bokhari, a senior economist with Redfin real estate brokerage in Cambridge, Mass.

“The education achievement gap is tied in with redlining because the lack of investment in black neighborhoods included a lack of investment in schools,” says Bokhari. “A quality education at a private school or paying for college is out of reach for many families who haven’t built wealth in their homes. The education gap limits opportunities for a college education and for a better job, which in turn affects income levels.”

Black buyers are more likely to be denied a mortgage loan approval than whites, which adds another major obstacle to closing the homeownership gap. According to a recent study from LendingTree, black home buyers are denied mortgages 12.64 percent of the time; the overall mortgage denial rate is 6.15 percent. It’s not just buyers who face a more difficult time getting a loan approval: LendingTree found that black homeowners were denied mortgage refinance loans 30.22 percent of the time, while the overall denial rate is 17.07 percent.

“Access to credit is a major problem,” says Jung Hyun Choi, a researcher with the Housing Finance Policy Center at the Urban Institute in Washington. “Due to tight credit following the Great Recession, many black households could not buy homes. Home prices have increased a lot since 2012, which means that many black households lost opportunities to build wealth.”

The FICO credit score system is structured to favor people who use credit, such as credit cards and car loans, but blacks and Hispanics tend to use less credit, says Christensen. She recommends increasing access to credit by relying on rent payment history for people who don’t use credit cards.

“It’s hard to close the race gap in homeownership when everything is stacked against blacks,” says Bryan Greene, fair housing policy director for the National Association of Realtors (NAR). “It’s myopic to look at immediate qualification standards and ignore that people are trying to overcome a century-old legacy of official disadvantage in housing and, on top of that, social dynamics and a lack of political will to fix this.”

The pay gap between whites and blacks is part of the problem, says Williams.

The black homeownership gap

“Systemic racism leads to lower rates of education and lower incomes among blacks, which in turn lead to lower credit scores and a lack of savings,” says Chris Herbert, managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. “That accounts for about three-quarters of the homeownership gap, but one-fourth couldn’t be directly explained by lower incomes and lower rates of education.”

An Urban Institute report found that because of knowledge transfer and down payment assistance from relatives, white young adults whose parents own a home are more likely to become homeowners. For those under age 35, a white high school dropout whose parents are homeowners is more likely to buy a home than a black college graduate whose parents are renters, according to the report, even though higher levels of educational achievement usually lead to higher rates of homeownership.

While other racial groups regained levels of homeownership since the foreclosure crisis, blacks continue to lag, says Herbert.

“Black homeownership rates are noticeably lower among people in their 40s and 50s because they were victims themselves of subprime loans or saw their parents lose their homes to foreclosure in larger numbers than white people,” says Herbert. “That naturally makes them skittish about trying to buy now and has a lingering impact on their finances.”

Between January 2007 and December 2015, homes in primarily black communities were twice as likely to face foreclosure than homes in white communities, according to a study by Zillow.

“Our analysis found that black homeowners have greater difficulty sustaining homeownership and are more likely to buy a home later in life,” says Choi. “They are also more likely to switch back to renters once they own a home, which means they are much less likely to be build equity and household wealth via homeownership.”

The housing crisis hit black households harder than white households, in part because they were targets for subprime lenders, says Choi. In addition, she says, foreclosure is contagious because it decreases home values throughout a neighborhood.

“If you’re living in an area with no upward mobility and no social network to help you get a better education and find a better job, then you’re deprived of opportunities to buy a home and build the home equity that you can invest in your family and your future,” says Bokhari.

Why homeownership matters

The most crucial impact of the racial homeownership gap is that consistently owning a home provides an ability to build wealth. Homeowners’ median net worth is 80 times renters’ median net worth, according to a 2019 Census Bureau study. That same study found that whites had a median household wealth of $139,300, compared with $12,780 for black households.

“An important factor of homeownership is the ability to pay the loan off and live rent-free in retirement,” says Herbert. “Without pension plans, people today are dependent on Social Security and their savings, so a rent-free home is an important third leg of financial security in retirement.”

Owning a home provides wealth that you can pass on to future generations, says Greene.

In 2019, 32 percent of first-time buyers received a gift or loan from a relative or friend to help make a down payment on a home and 21 percent of all buyers received financial help from a parent or other relative for their down payment, according to NAR.

Henderson Faribault, the grandfather of Mary Pherribo’s husband, became a chef after his emancipation from slavery. Upon his death in 1901, Faribault left a home for each of his eight children. (Courtesy of Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, University of North Carolina at Greensboro)

Henderson Faribault, the grandfather of Mary Pherribo’s husband, became a chef after his emancipation from slavery. Upon his death in 1901, Faribault left a home for each of his eight children. (Courtesy of Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, University of North Carolina at Greensboro) “Blacks are less likely to get that down payment assistance from their parents if their parents don’t own a home themselves,” says Herbert.

In addition to financial support, passing on the experience of homeownership from one generation to another provides a path to family wealth building.

“The research on the social benefits of homeownership is a little squishier than the wealth benefit, but there have been academic studies that show that residential stability, whether in a long-term rental or homeownership, provides better outcomes for children in terms of their school performance,” says Herbert. “There’s also some evidence that that magic sauce for community engagement is linked to the amount of time someone lives in a community. Homeowners tend to stay in their community longer than renters.”

The sense of community pride, of building something for your children and grandchildren, can spread in a variety of ways, says Christensen.

“The choice someone makes about buying a home will impact the way generations will think of themselves and increase their demand for great schools, great health care and more amenities in their neighborhoods,” says Christensen.

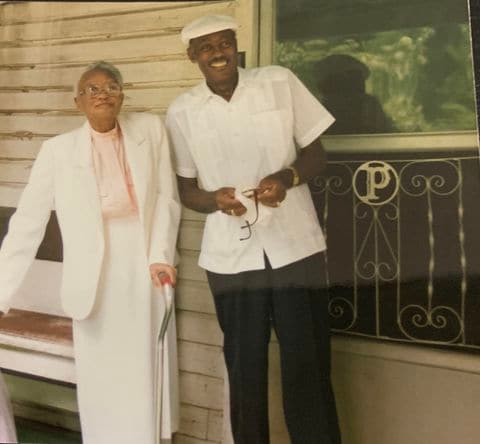

Mary Pherribo poses with her son John Pherribo. (Courtesy of Tai Christensen)

Mary Pherribo poses with her son John Pherribo. (Courtesy of Tai Christensen) Possible solutions

In addition to addressing the systemic problems of discrimination, low quality schools and limited access to higher paying jobs, homeownership education is key to increasing black homeownership rates.

“This is a generational issue,” says Williams. “We started an initiative last year we call the ‘House then the car’ to start the conversation with millennials about why buying a house is so important to build wealth.”

Community outreach to encourage black homeownership should be a prime priority, says Christensen.

“We want to create a community of comfort to get people talking to lenders and agents about the benefits of homeownership and to overcome their fears,” says Christensen. “We need to start at the baseline and help people understand how property taxes and insurance work and who they can call if they have trouble with their home or their loan.”

Tai Christensen, great-granddaughter of a woman who bought a home in 1936, is building a home with her family in Eagle Mountain, Utah. Pictured from left: Tai Christensen; her three daughters Maya, 14; Kelsey, 17; and Dylan, 8; and her husband, Adam Christensen. (Courtesy of Tai Christensen)

Tai Christensen, great-granddaughter of a woman who bought a home in 1936, is building a home with her family in Eagle Mountain, Utah. Pictured from left: Tai Christensen; her three daughters Maya, 14; Kelsey, 17; and Dylan, 8; and her husband, Adam Christensen. (Courtesy of Tai Christensen) [Historically black beach enclaves are fighting to save their history and identity]

Down payment assistance programs, including grants and loans, are essential to support new home buyers. Another option, suggests Herbert, is to use the tax code to match savings in individual development accounts or shield those savings from taxes to incentivize people to save for a home.

“There’s a program on the books right now, the Native American Home Loan Guarantee program from HUD, that needs to be expanded for blacks,” says Williams, referring to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. “The program offers loans with interest rates as low as 2 percent and lower down payment requirements.”

Adjusting credit score models to allow for utility bills or rent to be included or to find other ways to evaluate a borrower’s creditworthiness is another way to be more inclusive to blacks, says Bokhari.

“Reparations are also an interesting idea that people are talking about as a way to make up for lost wealth due to discrimination,” says Bokhari. “In 1865, some former slaves were offered ’40 acres and a mule’ so there is some precedence for some kind of reparations.”

One of the issues with combating discriminatory housing practices is that people often don’t know they’re being treated differently or given fewer opportunities than others, says Greene.

“That’s why the real estate industry needs to maintain extremely high standards and provide implicit bias training to avoid inadvertently treating someone unfairly,” says Greene. “We’re enforcing our [NAR] Code of Ethics and support Fair Housing [Act] testing by the government and private groups.”

NAR also recommends strengthening the FHA loan program, increasing access to down payment assistance programs, expanding alternative credit scoring models and building more homes to increase the supply of affordable homes, including in Opportunity Zones, a tax incentive program that encourages development in underserved neighborhoods. However, not everyone agrees that Opportunity Zones provide a path to homeownership.

“Opportunity Zones are a tax relief program for wealthy people and doesn’t call for homeownership opportunities for people who live in those neighborhoods,” says Williams.

Undoing centuries of discriminatory practices will take a concerted effort by the government, the real estate industry, financial institutions and nonprofit organizations to close the homeownership gap, Williams says.