Scranton became shorthand for the past. Its reality is far more complicated.

“Scranton doesn’t have six degrees of separation; we have two degrees,” says Maureen McGuigan, Lackawanna County’s deputy director of arts and culture. No, counters Durkin, it’s only one.

“What was our biggest export after coal?” asks unofficial historian Dominic Keating, a font of all Scrantonia. “It was our people.”

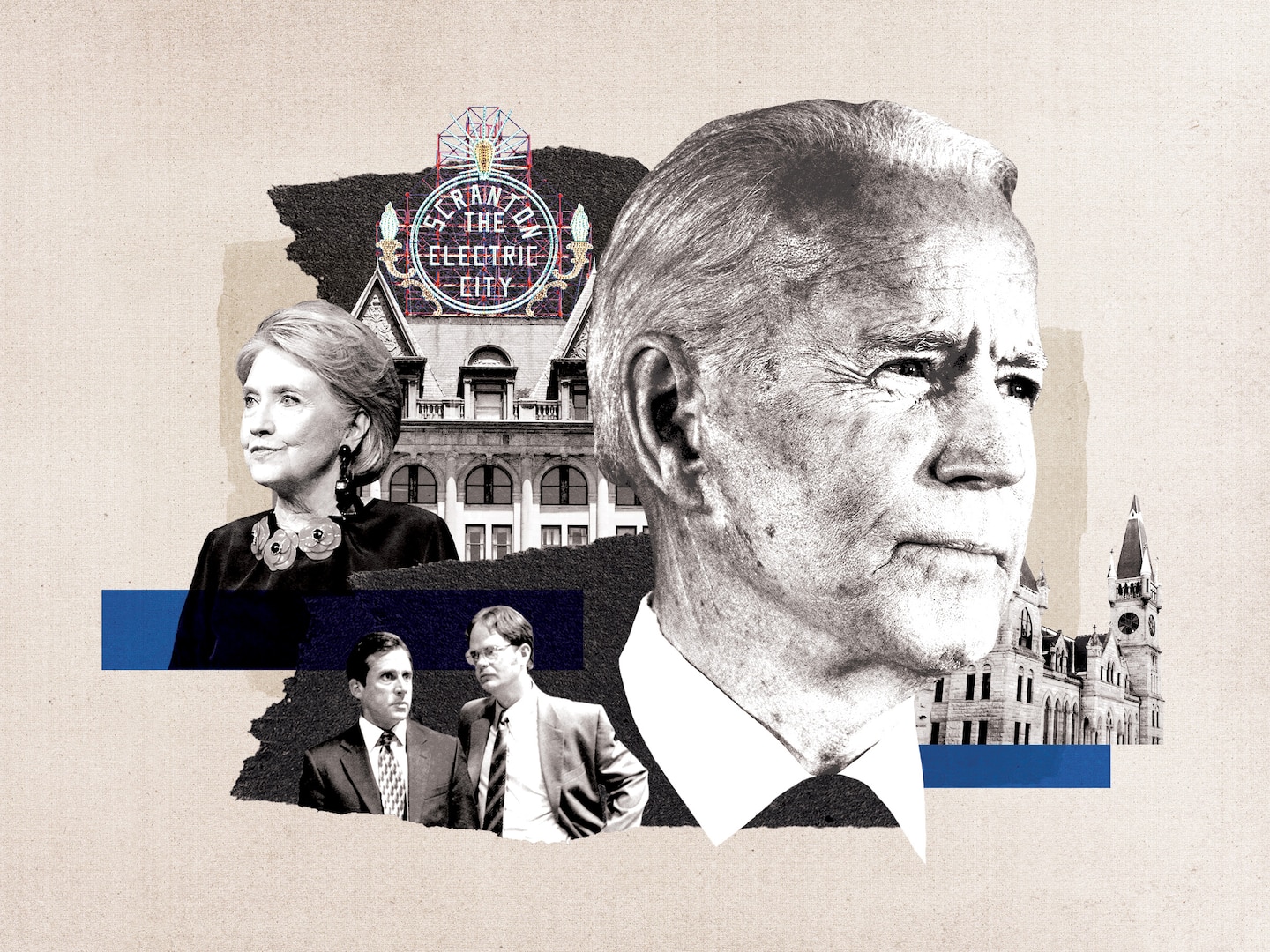

Scranton may be the best-known small city in America, a home to nearly 77,000 that looms large in the nation’s imagination, yet its reputation is often rooted in political rhetorical flourishes, 1950s nostalgia and a Van Nuys television studio take on the town.

The sepia-tinted myths often overshadow its contemporary truths, making it as much an idea as a locale. This mythology has been promoted by “The Office,” by Hillary Clinton, by President Trump and, of course, by native son Joe Biden, who’s now the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee. Says county historical society director Mary Ann Moran-Savakinus, “It is the ancient history that has created the image of Scranton today.”

The city has long been the foundation of Biden’s origin story, though he left Scranton at age 10. In 2008, Barack Obama introduced his vice presidential pick as “still that scrappy kid from Scranton who beat the odds,” when that kid was 65. Scranton is a constant in his speeches, a conceit in his memoir and a perennial campaign pit stop. Earlier this month, Biden visited nearby Dunmore to unveil his economic plan before making the requisite drive-by photo op at the dove gray, three-story homestead on North Washington Avenue.

Scranton was a cornerstone of Clinton’s biography in her 2016 presidential bid, though she was born and raised in the Chicago area. She spoke of her grandfather and father’s years here in a neighborhood known as The Plot, of their jobs at the nearby Scranton Lace Company, now shuttered with yellowed curtains, and of her summer visits to nearby Lake Winola. Both her parents are buried here.

The Rodham home is more modest, and in a more working-class neighborhood, than the Biden home in leafy Green Ridge, blocks from historic mansions. But Scrantonians more often mention the two former governors who were longtime residents — Republican Bill Scranton and Democrat Robert P. Casey Sr. — or that Pennsylvania’s senior senator, Bob Casey Jr., still lives here.

Scranton is the setting of nine seasons of “The Office,” the beloved sitcom that may well flourish forever in streaming and syndication. The city serves as a central character as imagined by a gaggle of Hollywood writers, representing small-city life slightly past its sell date and immune to cool. “I didn’t know very much about Scranton,” Greg Daniels, creator of the American adaptation, said in 2013 about picking it as the show’s location. “I just kind of knew it had a heyday maybe more in the past than the present.”

The “Office”-ized Scranton is “a place nobody would ever really want to live in for any particular reason,” says Mayor Paige Gebhardt Cognetti, who took office in January. Yet Scrantonians love the show.

Scranton, Biden likes to say, defines him. “Home is where your character is stamped, where it’s stamped into your soul, where your values are set,” Biden said here in 2016. He rarely fails to mention “the grit, courage and determination of people who never, ever give up.” Last fall, Biden launched not one but two campaign videos: “Scranton Values” and “A Kid from Scranton.”

In 1953, the Bidens became part of Scranton’s leading export, moving to Claymont, Del., a Wilmington suburb known for not much at all. Young Joe returned to Scranton often to visit his Finnegan grandparents and extended family. Later, he moved to Wilmington, his home to this day, a city known as a corporate tax haven in a state that barely registers on the map. Scranton is essential in telling voters who he is. So is winning Pennsylvania’s prized 20 electoral votes.

“If I was from Delaware, I’d be very upset with Biden going on about Scranton,” says Paul Catalano, sitting in his Italian market, where the hoagies sell out by early afternoon and the political talk goes all day. “He represented that state for 36 years and has lived there most of his life.”

Catalano, it should be noted, is the two-time former chairman of the county Republican Party. He sits below a photo of himself with Eric Trump. (The Biden campaign did not return a request for comment on this story.)

Lackawanna County is a Democratic stronghold, surrounded largely by a sea of red. Pennsylvania’s sixth-largest city also lends itself to political stagecraft for presidential candidates who don’t have family ties here, sometimes to spite those who do. Donald Trump stumped here the day Biden addressed the 2016 Democratic National Convention, and returned on election eve while Clinton campaigned in Philadelphia. He vowed, “We are going to put the miners back to work, the steelworkers back to work,” though the anthracite coal mines closed in the ’60s and the iron works last fired in 1902.

“Not only do we not want coal mining, it’s not possible,” Durkin says. The coal has been mined out. Trump was selling a story of Scranton so long gone few remember it. He narrowly lost Lackawanna County but won the state, the first Republican to do so since 1988.

“We’ve come a long way from when we were considered as ‘the Armpit of America,’ ” McGuigan says.

The publication that considered Scranton as a contender for the title happens to be The Washington Post. “Wilkes-Barre, Pa., may be awful, but next-door neighbor Scranton is awfuler,” Gene Weingarten wrote in 2001, “and Scranton has a certain likable pugnacity that comes from knowing you are famously crummy and not giving two hoots.”

He bestowed the title on Battle Mountain, Nev., but Scrantonians have long memories, especially about Scranton. They give at least one hoot. And there are many ways in which it was never an armpit.

Urban renewal never came to Scranton, a city of hilly neighborhoods cradled in the Lackawanna Valley. No one was in any hurry to tear down stuff to make way for something shiny and new. Downtown is composed of majestic late 19th-century and early 2oth-century buildings and the spectacular “Scranton: The Electric City” sign, now illuminated with LED lights. They’re monuments to a richer, busier city that reached its population zenith on the cusp of the Depression, at almost twice the size it is today. “They’re emblematic of our onetime greatness,” says Keating, the unofficial historian, offering a tour around Courthouse Square. Scranton’s tallest building, the 14-story Bank Towers, is more than a century old.

The city’s moniker, the Electric City, is qualified, Keating says. Scranton wasn’t home to the first electrified trolley system; it was home to “the first successful, continuously operating electrified trolley system.” Today the trolleys are in a museum. So is the coal. The iron furnaces are a state heritage site. The sumptuous 1908 Lackawanna Train station is a Raddison hotel.

Scranton is a historic stage set, picture perfect for political rallies. There’s a cruel irony that “The Office” chose not to film here.

“We don’t have whatever other cities had, including their problems,” Moran-Savakinus says. “We didn’t grow that way. Our industry just left.” Iron, steel, coal, lace, garment manufacturing and, yes, paper. And with them, jobs and residents. Some new industry arrived — Biden visited a metal works to announce his economic plan — but never again on the same scale.

Scranton, a city of neighborhoods marked by churches and hoagie shops, became political shorthand for industrial and gritty. Yet it’s neither. Scranton’s biggest employers are largely eds and meds — it added a medical school in 2008 — as well as local, county and federal government. Downtown is spotless. The end of coal meant a cleaner, more verdant Scranton.

There’s a vegan restaurant, a hipster barber shop. The former Stoehr & Fister department store is being converted into loft apartments. Scranton has a Fringe arts festival.

“People born and raised here, they think it’s the center of the universe, and you can’t change their minds about it,” says Joshua Mast, who owns two restaurants with his partner. (“There is a gay community,” he says, “but it’s not an organized gay community.”) He also notes: “Scranton doesn’t have those highs, it doesn’t have those lows. It just hums along.”

Well, except for politics. Northeastern Pennsylvania — NEPA — gained notoriety as a nexus of political corruption. Last year, former mayor Bill Courtright pleaded guilty to charges of bribery, conspiracy and an attempt to obstruct commerce by extortion. Two former county commissioners were convicted of bribery, conspiracy, racketeering and tax fraud.

“There hasn’t been a lot of political will to do things that were supposed to be done over the years,” says Cognetti, the Democratic mayor. “This city needed a jolt.”

Scranton has been under Pennsylvania’s Act 47, which assists economically distressed municipalities, since 1992. The median annual income is around $40,000. The pandemic hasn’t helped.

Still, residents are hopeful. Cognetti, 39, is Scranton’s first female mayor. She has an MBA from Harvard and served in the Obama administration. She is also the first mayor born outside the city, having moved here four years ago after she married a Scrantonian. After Courtright’s ignominy, residents appear as elated by her outsider status as they are about her gender. They’re quick to point out that women now represent the overwhelming majority on the school board, the city council includes its first openly gay member and, yes, change can come to Scranton, even if it takes a while.

The city’s new marketing initiative is “Work from Here,” selling Scranton as a relatively affordable city to stake a home office, two hours from New York and Philadelphia. Handsome houses sell for $200,000; mansions — should you want a mansion — for less than half a million.

“We’re not the dying Rust Belt city that Trump described,” Cognetti says. “Scranton is an inland destination for people priced out of a bigger city.”

Durkin mentions the city’s proximity to mountains, outdoor activities, major highways — everyone mentions the proximity to the highways. It’s also easy for politicians to get to for the evening news, a short zig off the elite coast. When I mention I was trying to reach Biden’s old friend, Tom Bell, Durkin says, “I’m playing golf with his brother at 4:30. I’ll ask him.”

Two degrees of separation.

Tom Bell, 77 — “Tommy” in Biden’s storytelling — has become, by default, the custodian of Biden’s childhood as members of the old guard have died or are in failing health. A few Sundays ago, Bell says, Biden called to help him recall a story from their youth in Green Ridge and at St. Paul School.

“He’s a very loyal, emotional guy on certain things. He was a wily, tough kid. He was a real risk taker,” says Bell, who works in insurance and has lived here all his life. “He would do anything. He was a chancey guy, holy Christ.” He tells stories of when Biden pulled the electric power line off the trolley, the time he jumped on a burning culm dump for a $5 bet, the time he was asked to beat up a bully to “straighten him out” — and did.

“It’s a different town altogether. It’s matured. It’s seasoned,” he says.

Scranton “means a lot to Joe. It’s a nice town, homey,” he says. “The true values of life are seeded in Scranton more than other places.”

During this election season, Scranton is a stand-in for appealing to working-class America, and not only for Biden. Trump held a Fox News town hall here in early March.

Character, that’s what Biden is promoting, and that’s what Scranton offers. For Biden, it represents authenticity and identity. With Pennsylvania being a battleground state, Americans are likely to hear a lot more about Scranton, and all that it represents to its most famous 77-year-old kid.

“Every single person, my dad used to say, is entitled to be treated with dignity,” Biden said at an October rally here. “Dignity — a word I think is used more here in Scranton, at least in my experience, than anywhere.”

Outsiders remain astonished at the city’s national image. “For such a small city, it has such a large presence in people’s imaginations,” says University of Scranton sociologist Meghan Rich. But “it’s hard to break into the community if you’re not local.” She didn’t. Rich moved to Baltimore and commutes.

“It is one of the most relaxing places to live,” says McGuigan, the county official, which would make it the opposite of its popular perception. People revel in how quickly they can leave their offices and get to the mountains, the rivers, the links. And, at 4 p.m. on a recent Wednesday, the parking lot at Pine Hills Country Club appeared filled.

Read more: