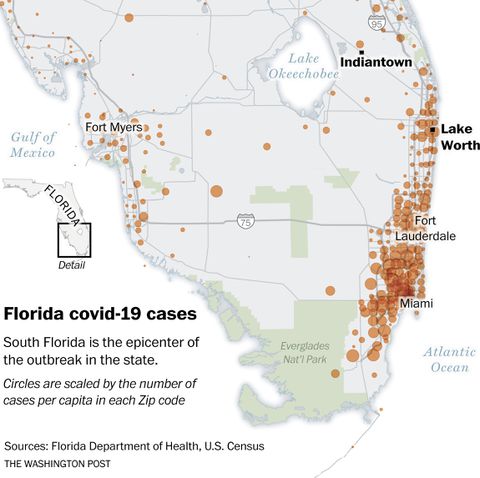

For Guatemalans in Florida, essential work leads to a coronavirus outbreak

LAKE WORTH, Fla. — The thousands of Guatemalan men who manicure the golf courses and gated communities of South Florida were deemed essential workers, so Alfredo continued taking the journey every morning, until almost everyone he knew was sick.

At 6 a.m., the 39-year-old left his home here, on a quiet street in one of the largest indigenous Guatemalan communities in the United States. By sunrise, he’d be in Boca Raton or West Palm Beach or Miami, trimming trees in the wealthiest neighborhoods between the Atlantic Ocean and the Everglades.

For the past 30 years, tens of thousands of men and women from northern Guatemala, descendants of the Mayan empire, have enabled one South Florida construction boom after another. Now, asked to work through the coronavirus pandemic, they are among the hardest-hit populations in the state, reporting more new cases each day than any other.

“It’s a crisis within a crisis,” said Samuel Matos-Bastidas, an instructor at the University of South Florida now working as a contact tracer with the state health department assigned to the indigenous Guatemalan population.

More than 30 percent of those tested in Palm Beach County’s Guatemalan-Mayan community — a population of around 80,000 — have been diagnosed with the novel coronavirus, three times the state average. Many believe the infection rate to be far higher. Of 130 families enrolled in an early-childhood education program through Lake Worth’s Guatemalan-Maya Center, for example, 80 have been infected.

Alfredo saw how the virus made its way into the community. When he started feeling sick, the owner of his landscaping company sent him and eight close co-workers to be tested. Alfredo and five others tested positive. Within days, his 6-week-old daughter became sick, too, her temperature reaching 106 degrees, he said. She tested positive and was sent to intensive care.

A line of people, most of them essential workers, wait to be tested for the novel coronavirus in a Lake Worth park. (Cindy Karp)

A line of people, most of them essential workers, wait to be tested for the novel coronavirus in a Lake Worth park. (Cindy Karp) “My boss explained it to us. He said, ‘Landscaping is essential. We’re going to keep working,’ ” said Alfredo, who asked that his last name not be used because, like his co-workers, he lacks legal status in the United States. “By June, we were pretty much all sick, and we brought it back to our families.”

The same thing happened in Indiantown, the mostly Guatemalan community 45 minutes west of Palm Beach, where many of Florida’s first indigenous Mayans arrived in the 1980s, fleeing their country’s civil war. Officially, 10 percent of the city has tested positive for the virus, among the highest rates in the state.

Several of Indiantown’s founding members have now died. There was Mathias Balthazar, the town’s best-known marimba player; Francisco Marcos, one of the leaders of the church; Pascal Martínez, who helped disburse money from one of the community’s emergency funds.

Even after South Florida’s Mayan population became the backbone of the area’s labor force, many here still weren’t aware of its existence. Over the last few weeks, its patriarchs died as local celebrities, largely unknown outside of their immediate communities.

[Coronavirus on the border: California hospitals overwhelmed by patients from Mexico]

In some cases, their bodies have been frozen, so they can be sent back to Guatemala for burial when the border reopens.

Despite having steady work, the community in Indiantown has an acute housing shortage. Run-down houses rent for up to $1,600 monthly, space and costs shared by groups of men and multiple families. Workers pay $500 for a bed. Even couches are let. A dozen or more people share a single mobile home. For years, community members say they’ve asked the county and state for more affordable housing. None has been forthcoming.

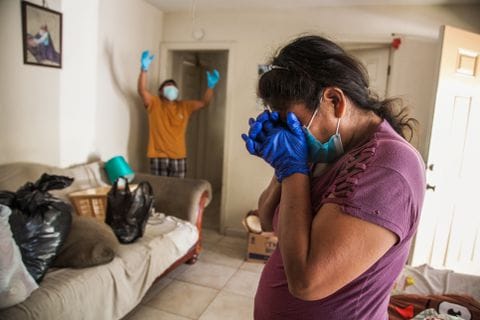

A woman and her husband pray in their Lake Worth home. Her husband had recently returned home from two weeks of hospitalization due to respiratory complications related to covid-19. She had been diagnosed with the virus the day before. (Cindy Karp)

A woman and her husband pray in their Lake Worth home. Her husband had recently returned home from two weeks of hospitalization due to respiratory complications related to covid-19. She had been diagnosed with the virus the day before. (Cindy Karp) Community members say the crowded living conditions have facilitated the spread of the virus.

“They don’t want to see what’s happening here until a pandemic comes,” said Juan Carlos Lasso, the director of religious education at Holy Cross Catholic Church in Indiantown, now backlogged with funerals. “Now they say it’s because everyone is living together.”

George Stokus, the assistant administrator for Martin County, said housing has been a challenge.

[Mexico’s Central de Abasto: How coronavirus tore through Latin America’s largest market]

“There has been a consistent desire for affordable housing and the county has been addressing it, but maybe not at the rate they’re asking for,” Stokus said. “The private sector has had a lot of questions of product viability of home building in Indiantown.”

Across the country, immigrants both documented and undocumented have been declared essential workers, needed to staff poultry plants and farms and ranches, offering a glimpse into the inextricable link between migrant labor and the American food supply. In South Florida, where the tropical summer sends nearly everything with roots into bloom, and where another housing boom is underway, it was the Guatemalans who were asked to keep working. During rapid-fire conversations between workers in Spanish or Mayan languages, the word “landscaping” is the only one uttered in English.

Patrons at a Lake Worth laundromat are required to wear protective masks. Many essential workers, often assisted by their children, take advantage of Sundays to do their laundry. (Cindy Karp)

Patrons at a Lake Worth laundromat are required to wear protective masks. Many essential workers, often assisted by their children, take advantage of Sundays to do their laundry. (Cindy Karp) “We immediately knew the community wasn’t going to be hit by joblessness,” Lasso said. “You have to maintain everything so beautiful.”

While other activities shut down, converted school buses painted white continued to pick up dozens of workers at a time in Lake Worth and drive them to beachfront houses and into the suburbs (President Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate is five miles away). In Indiantown and Fort Myers, workers piled into pickup trucks and vans. Through May, few wore masks. Many believed the virus could be treated with traditional medicines, such as herbal teas. They speak primarily Mayan languages, which the state did not use to disseminate information about the virus.

As Florida’s caseload surged last month, Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) singled out “overwhelmingly Hispanic” day laborers as a major cause for the spread.

“Some of these guys go to work in a school bus, and they are all just packed there like sardines, going across Palm Beach County or some of these other places, and there’s all these opportunities to have transmission,” DeSantis told reporters in Tallahassee.

Workers criticized DeSantis for seeming to blame them for the spread of the virus without acknowledging the structural challenges, such as poor housing and working conditions, that made it difficult to avoid getting sick.

Florida health department spokesman Alexander Shaw, asked about the outbreak among Guatemalans, responded in a statement that officials are “engaging with farming communities and migrant camps to strengthen and foster relationships by distributing cloth face coverings and covid-19 testing opportunities.”

A mother holds her daughter while the child gets a nasal swab at a drive-through covid-19 testing site in Lake Worth. (Cindy Karp)

A mother holds her daughter while the child gets a nasal swab at a drive-through covid-19 testing site in Lake Worth. (Cindy Karp) In her garage on the outskirts of Lake Worth, María Hernández broadcasts Radio Ketconop, mostly in her native language of Q’anjob’al, to tens of thousands of listeners across the United States and Guatemala. She came to the United States from San Miguel Acatán, a tiny village in the mountains of northern Guatemala, in 1986. Thousands more indigenous Guatemalans, many from the same village as Hernández, have arrived in waves — families fleeing the civil war in the 1980s, single men in the late 1990s, a boom of unaccompanied teenagers in 2014, parents and their young children in 2018 and 2019.

Hernández broadcasts updates on the pandemic in both Guatemala and Florida. In San Miguel Acatán, she said, there were almost no cases. In Florida, the virus exploded across her community. Some migrants started talking about leaving the United States to get away from the pandemic. As members of the community died, she live-streamed funerals on her Facebook page so family members in Guatemala could mourn remotely.

“It’s time for us take care of ourselves. I see people walking and biking without masks,” she said in a broadcast last week. “The Anglo-Saxons, or white people, are taking care of themselves, but we aren’t.”

By June, the state of Florida began to recognize the surging caseload within the Guatemalan population. The Guatemalan-Maya center in Lake Worth offered free weekly tests. The health department began reaching out to Mayan interpreters, including Hernández. Some employers are now asking workers for proof of negative test results before they can resume work.

But every day, thousands of Guatemalans are still traveling together to their landscaping or construction sites, and returning to crowded homes.

A 3-year-old girl in Lake Worth uses a nebulizer daily to inhale vaporized medication as she recovers from the novel coronavirus. She lives with her parents, 8-year-old sister, two teenage brothers and another woman with two daughters. They all had covid-19 at the same time. (Cindy Karp)

A 3-year-old girl in Lake Worth uses a nebulizer daily to inhale vaporized medication as she recovers from the novel coronavirus. She lives with her parents, 8-year-old sister, two teenage brothers and another woman with two daughters. They all had covid-19 at the same time. (Cindy Karp) In a two-bedroom apartment off a main street in the city of Fort Myers, 12 Guatemalan men, women and children share four mattresses. Three of the men work for a landscaping company. The fourth lays pipe for the county. Two women work at local restaurants. Five children stayed at home taking online classes. In June, they all got sick.

The adults in the house continued to work, even though they were symptomatic. Many of the Guatemalan workers that Matos-Bastidas interviewed said they believed if they stopped working, they would lose their jobs. That same belief guided the residents of the Fort Myers apartment.

“We have rent to pay, food to buy,” said Juan, one of the men in the apartment, who asked that his last name not be used because he lacks legal status. “If we don’t work, we don’t have any way to pay.”

Part of the urgency came from the economic paralysis in Guatemala, whose government had mandated a strict lockdown. Guatemalans with relatives in Florida are now more in need of remittances than ever before. Juan sent $300 per month back to his native Quiché. His wife asked for food. His parents had medical bills from non-covid illnesses.

Eventually, everyone in Juan’s Fort Myers apartment recovered. They kept their negative test results to show their employers. Then a neighbor knocked on their door.

Everyone in the next-door unit — eight people sharing two bedrooms — had become ill.

Photo editing by Chloe Coleman. Copy editing by Briana R. Ellison. Graphic by Tim Meko. Design and development by Allison Mann.