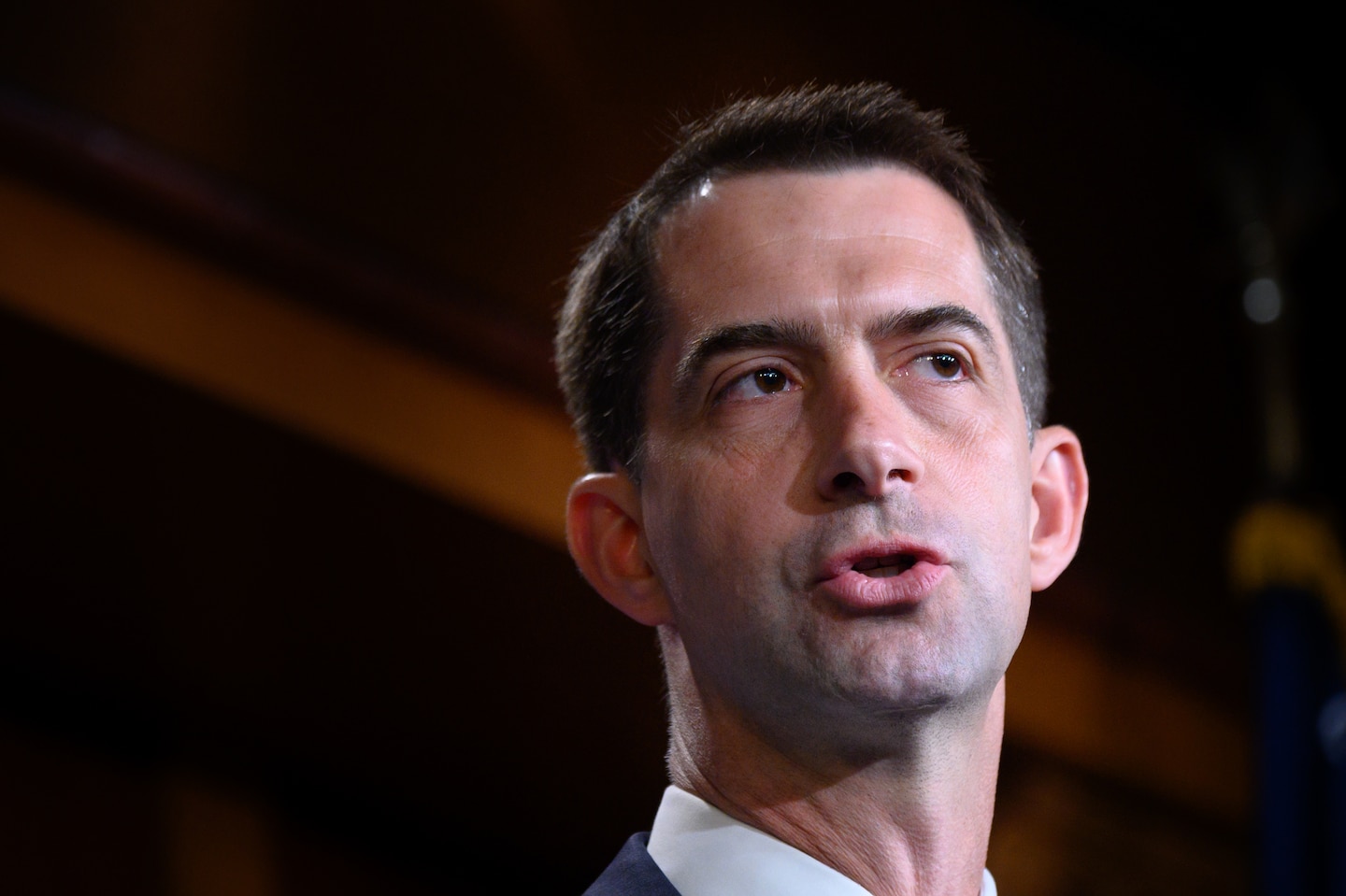

Sen. Tom Cotton wants to take ‘The 1619 Project’ out of classrooms. His efforts have kept it in the spotlight.

“As the Founding Fathers said, it [slavery] was the necessary evil upon which the union was built,” he told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette over the weekend. “The union was built in a way, as Lincoln said, to put slavery on the course to its ultimate extinction.”

His comments ignited a war of words on social media Sunday, with politicians, media figures and journalists — including the project’s creator, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who won a Pulitzer Prize for one essay — accusing the senator of endorsing the idea that slavery was a “necessary evil,” as Cotton insisted that he was simply reflecting on what the Founding Fathers believed at the time.

The online debate highlighted the fact that even amid a persistent, intense examination of racial justice across the United States — one that emerged on the streets of Minneapolis, spreading to suburban kitchens, corporate boardrooms and Capitol Hill itself — “The 1619 Project” remains a lightning rod for some conservative lawmakers, on race, media, history and many matters in between.

Nearly a year after President Trump decried the project as a “Racism Witch Hunt,” Cotton’s bill shows that “1619″ continues to receive nearly as much criticism from Republicans as it did in the days following its publication as a special stand-alone issue of the New York Times Magazine.

When Hannah-Jones won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in the spring, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) slammed it as “propaganda.” Earlier this month, amid news that Oprah Winfrey would be adapting the project into a TV series, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed that it rehashed “the Marxist ideology that America is only the oppressors and the oppressed.”

“The Chinese Communist Party must be gleeful when they see the New York Times spout their ideology,” he said during a speech at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, The Washington Post’s Carol Morello reported.

Now that the series of essays has been adapted into lesson plans and several major school districts — including those in Chicago, Washington and Buffalo — have moved to formally adopt the curriculum, Cotton wants to prohibit K-12 districts from using federal funds to teach the project at all.

“The entire premise of the New York Times’ factually, historically flawed 1619 Project … is that America is at root, a systemically racist country to the core and irredeemable,” the senator from Arkansas told the Democrat-Gazette. “I reject that root and branch.”

“The way that history is taught in American schools is highly politicized and it really has a nationalistic agenda,” she said. “What that has meant is that it has necessarily downplayed the role of slavery.”

Her efforts have drawn critiques from academic circles, too. Late in 2019, five notable U.S. historians wrote to the Times expressing serious concerns about the historical framing of the project, asking for corrections about the role of slavery in colonists’ motivation for fighting the Revolutionary War. The publication’s magazine said it stood behind the project, though it also added a clarification to the series addressing some of the historians’ complaints.

Cotton himself has been no stranger to stirring up controversy with his words in the Times. In June, the newspaper apologized after an op-ed from the lawmaker, titled “Send in the Troops,” called for the deployment of the military against the racial justice protests sweeping the nation. The Times later said the op-ed fell short of its editorial standards, and its editorial page editor, James Bennet, resigned shortly thereafter.

Whether Cotton’s statements about slavery, the founders and history are accurate sparked another wave of debate.

In an interview with The Post, John P. Kaminski, a historian at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, said that many Southerners defending the practice did in fact refer to slavery as a “necessary evil.”

A number of mechanisms within the country’s founding documents, such as the three-fifths compromise, and the omission of the word “slavery” from the Constitution, he added, indicate that it was not supposed to last forever as an institution, but was placed second to the maintenance of the union.

“Any discussion that we would have of slavery and racial relations today has to be understood in the context of the 18th century, where racism is profound throughout the entire Western world,” said Kaminski, who edited the book, “A Necessary Evil? Slavery and the Debate Over the Constitution.” “The country was pretty well divided at that time in many respects the way the country is divided today.”

Later in the evening on Twitter, Cotton insisted that he was merely rehashing a historical perspective, rather than stating his own.

“Describing the *views of the Founders* and how they put the evil institution on a path to extinction, a point frequently made by Lincoln, is not endorsing or justifying slavery,” he wrote.

But Joshua D. Rothman, a University of Alabama history professor, countered Cotton’s argument, writing that slavery was neither a “necessary evil” nor destined for “ultimate extinction.” It was more nuanced than that, he said.

“Slavery was a choice defended or accepted by most white Americans for generations, and it expanded dramatically between the Revolution and the Civil War,” Rothman wrote.

If anything, though, the clash between Cotton and Hannah-Jones on Twitter seems to indicate some limited common ground: Both place heavy value on how slavery is taught in the nation’s classrooms. Where they seem to disagree is just what that history is, and how to teach it.

On Friday, Hannah-Jones said that Cotton’s bill “speaks to the power of journalism more than anything I’ve ever done in my career.”

“Imagine thinking a non-divisive curriculum is one that tells black children the buying and selling of their ancestors, the rape, torture, and forced labor of their ancestors for PROFIT, was just a ‘necessary evil’ for the creation of the ‘noblest’ country the world has ever seen,” she wrote on Twitter on Sunday.

And, as some pointed out, Cotton’s line about slavery being “built into” the country supports her core argument after all.

“So, was slavery foundational to the Union on which it was built, or nah?” she asked. “You heard it from Tom Cotton himself.”