After nearly 30 years, the game Magic: The Gathering is bigger than ever. The best players may also be teaching us about heroism.

Nine months ago, I went on a road trip to Richmond to see hundreds of people try to win $50,000 by playing a card game about swamps and elk and math. But the whole way there, I kept thinking about heroes.

We’ve often been uncomfortable with heroes — the book “A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich” dates to 1973 — but in an era when the world needed them more than ever, they seemed to be in short supply. Too many men — writers, actors, Founding Fathers — whom I had once believed to be worthy of admiration instead lay somewhere on the continuum between flawed human beings and bipedal Superfund sites.

In the immensely popular card game Magic: The Gathering, however, heroism is often distilled to its traditional essence: virtuous men and women going on quests to defeat unambiguously evil creatures like Massacre Wurms and Rune-Scarred Demons. I wanted to learn about the culture of the game and how it had managed to thrive a quarter-century after its debut, but I hoped that while I was there I might figure out some things about heroes, too.

In the months that followed, we entered a different world, where a handshake became a distant memory. When I thought of the crowded rooms that were an unremarkable part of life before the coronavirus pandemic, I remembered sweaty rock clubs, Greek restaurants, NBA arenas. But one building felt more like a dream than any of those: the Greater Richmond Convention Center, where nearly 500 men and women paired off in rows of card tables placed in a tight grid that looked as if it might extend to the horizon.

On a Friday morning in November, I was standing near one match, far enough away to give the players some space, but closer than six feet. I was watching two men locked in one-on-one combat, as ritualized in Magic: The Gathering. Their weapons were colorful playing cards. There were dozens of them on the table, including Paradise Druid; Beanstalk Giant; and Oko, Thief of Crowns, a trickster hero who can transform other creatures into elk. The tactical situation was complicated; both men stared intently at the cards, as if an unblinking gaze might improve them.

Lee Shi Tian and Logan Nettles were competing for a half-million-dollar prize pool in a Mythic Championship, one in a series of big-money Magic: The Gathering tournaments that in 2019 took place in London, Barcelona — and Richmond. It was a full convention hall, but a smidgen of players compared with the 40 million people who have played Magic since it went on sale in 1993 (according to the game’s publisher, Wizards of the Coast).

Nettles — then 31 years old, from Santa Ynez, Calif. — was wearing a black T-shirt with the words “Pro Tour” printed on it. Lee — age 32, from Hong Kong — had a gaudy fuchsia scarf around his neck. Neither of them spoke. Then Lee abruptly made a decision, quickly turning some of his cards to indicate an attack. Nettles considered the play for a moment and decided his position was hopeless. Shaking Lee’s hand, he resigned the match.

After Lee gathered his cards and departed, Nettles told me quietly, “He’s a high-profile player, a Hall of Fame guy. I’m a tier below.” (Magic does have an official Hall of Fame, honoring 48 of its greatest competitors.) Nettles had played enough matches against the world’s best Magic players to assess his abilities vs. theirs: “I make a mistake in three percent of the games, they might make a mistake in one percent, and that’s the difference in a tournament.” One minute you’re a hero; the next minute, you’re a goat. Or in this case, an elk.

In 2019, Wizards provided 32 top players with sponsorship contracts worth $75,000 and, almost as important, gave them automatic invitations to major tournaments. Nettles wasn’t in that tier, but he had played well enough at Magic tournaments to get a sponsorship from a company that makes protective card sleeves, allowing him to play the game for a living.

Even subcultures like Magic have celebrities and influencers and heroes, and the boundaries between those figures often get blurry. A hero can be somebody who does the things that other people can’t, whether that’s pitching a perfect game, leading a political movement or saving a life. But here’s the great magic trick of heroes: They inspire other people to unprecedented achievements of their own. However, since heroes teach the world that impossible feats are possible, their accomplishments can feel like a reproach: Why aren’t you doing the extraordinary yourself? Heroism seems more manageable when confined to a deck of cards.

Malcolm Beckford, left, and Jeffrey Cooper look at Magic: The Gathering cards for sale during the MagicFest event in Richmond in November.

Malcolm Beckford, left, and Jeffrey Cooper look at Magic: The Gathering cards for sale during the MagicFest event in Richmond in November. Players in Magic are rival sorcerers, playing cards that represent spells, some producing arcane effects, others summoning mystical beasts — all designed to damage the opponent. A player begins with 20 points, called “life,” and wins by reducing the opponent to zero.

The great innovation of game inventor Richard Garfield, one that Wizards patented, was that players assembled their own decks from packs of cards that they could buy as if they were baseball cards. (Some were particularly coveted: A first printing of the Black Lotus card sold at auction for $166,100 in February.) This proved to be a brilliant economic model, encouraging players in search of an elusive card to keep buying packs. It was also a breakthrough in game design: A lot of the strategy comes from how players construct their decks before play starts, finding clever synergies between cards.

Magic was the first game in a new genre, called collectible card games or trading card games. In the decade after it debuted in 1993, there were dozens of competitors, with themes ranging from Hong Kong action movies to warring vampires. Most of those games have fallen by the wayside (Pokémon is a notable exception), but Magic is bigger than ever. Wizards of the Coast prints cards in 11 languages, more than 20 billion cards between 2008 and 2016. The game has released 20,886 different cards in over a hundred expansion sets, gradually detailing its own fantasy multiverse with decades’ worth of adventures and dozens of tie-in novels. (“War of the Spark: Ravnica” debuted at No. 5 on the New York Times bestseller list in May 2019.)

Explaining the setting of Magic, Jeremy Jarvis, franchise creative director at Wizards, told me, “It’s a twist on the known superhero genre, where the heroes, the denizens, are powered by magic rather than mutations or technology.”

On a cold November morning, the magical planes of Ravnica and Dominaria felt very far away from the yellow cinder-block walls of Exhibit Hall A, but so did Hong Kong, the home of Lee Shi Tian. Lee still had a job in his hometown, a part-time position as an accountant. He told me that the prize money he had earned from Magic — $222,195 lifetime — didn’t necessarily validate his choice to pursue the game, but it had assuaged his family’s concerns that he was squandering his life. “Gaming is not a popular job in Hong Kong,” he said. Reminded that it wasn’t particularly common in the United States either, he laughed. Then he said: “What I’m trying to do is use my name in the gaming industry to tell people what is happening in Hong Kong. The police are abusing their power more and more. They are arresting people for no reason. Hong Kong is a well-developed place that should have democracy; we should have freedom of speech.”

At home, Lee had long been active in the city’s democracy movement. He was aware, however, that his outspoken support for Hong Kong’s independence from China risked government reprisals and might cost him his Magic career: “Every time I leave Hong Kong for tournaments, I think … hmm, maybe next time I will not be able to get past customs.”

Lee’s opponent for his sixth-round match was Andrew Cuneo. All the players in the convention hall knew that over the course of 16 Magic duels, they couldn’t afford to lose more than three or four matches. (Matches are best of three games.) Making it to Sunday, when only eight players remain, would be a major accomplishment for any of them. Cuneo had been playing Magic for 25 years and was revered as one of the game’s masterminds. “But I haven’t gotten to play on Sunday in 20 years,” he said.

He started playing Magic in 1993, as an undergraduate at Carnegie Mellon, and took some time off from the game to work as a computer programmer and play in weekend rock groups. “We were hobbyists that wanted to take it seriously but never really got there,” Cuneo said of his bands while chatting between matches. “For a lot of people, this game is a hobby that they want to be able to take seriously, and I get to actually do it.” The aspirational appeal of the Magic pro circuit — the idea that you can ascend from playing the game on Friday nights at your local card shop to traveling the world for major competitions — is why Wizards of the Coast spends millions on the Mythic Championship tournaments.

Cuneo, 44 and living in Philadelphia, had recently grown disenchanted with his job and fallen back into professional Magic. “This isn’t a great way to earn money, but it’s been good enough and it’s gotten a lot better lately,” he said. “Sometimes I do think, ‘Wow, this is weird that this is what I’m doing with my life,’ but to succeed, you have to throw yourself into it.”

Cuneo and Lee shuffled their own cards; then they exchanged decks and shuffled each other’s cards, ostentatiously turning their heads away as they did so to eliminate any chance of seeing the cards.

For me, the heroism of Magic seemed more meaningful every day: not the grand mythic gestures, but the accumulated moments of courtesy and decency, and the knowledge of the players that they were part of a subculture — which was another word for a society.

Magic: The Gathering releases new sets of tournament-eligible cards four times a year, regularly rotating old cards out of official play. (They even maintained that schedule during the pandemic, with only minor production delays.) That means strategies are constantly in flux, and the “metagame” historically has evolved as players discover dominant new deck archetypes and then develop countermeasures.

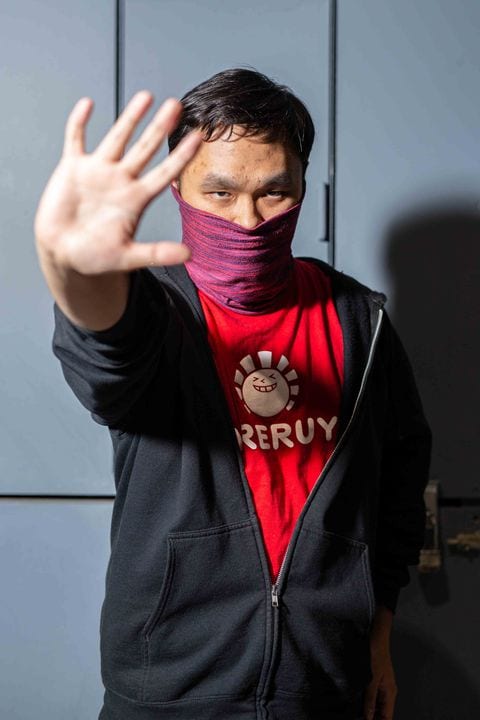

Lee preferred to construct decks that neutralized the dominant strategy — ideally in a way that nobody had prepared for — but decided that a deck centered on Oko, Thief of Crowns, while popular, was too powerful to pass up. Cuneo’s deck was a “Selesnya Adventure” design built to bring lots of small creatures into play — and that’s what happened against Lee. As Cuneo rolled out Edgewall Innkeepers and Lovestruck Beasts, Lee kept riffling through his deck. When Cuneo played a card called March of the Multitudes, it gave him over 30 creatures in play, an overwhelming advantage. Before the coup de grace, Lee unconsciously tugged on the shiny purple cloth around his neck, briefly pulling it up to his chin, revealing that it wasn’t just a scarf — it was a mask like the ones that street protesters wore in Hong Kong to protect their identities.

In November, before masks became a public-health necessity, HBO’s “Watchmen” series was brilliantly exploring the notion that masks could be value-neutral: They empower both heroes and white-supremacist mobs. At this moment, Lee’s face mask was purely symbolic — and, ironically, inverted the anonymity that a mask usually provided. By wearing one, he loudly proclaimed what side he stood on in Hong Kong.

When Lee placed in the top eight of the Mythic Championship in Long Beach, Calif., in October, he pulled the mask over his face for an official on-camera interview discussing his triumph. While most players’ Twitter feeds were filled with tournament reports, his became a clearinghouse of information about Hong Kong and its citizens’ fight against Chinese encroachment on their democratic values. “I try to yell as loud as possible to make people know what is going on,” Lee told me, “and hope they are willing to join me, willing to support us.”

A handful of other prominent players had used their Magic success to draw attention to issues: Craig Wescoe promoted veganism, while Autumn Burchett advocated for trans rights. The game is full of acts of vicarious heroism: By turning a small piece of cardboard 90 degrees, players can symbolically send a Dawnstrike Paladin on a quest to battle an Acid-Spewer Dragon. That didn’t inspire Magic players to run into burning buildings, of course, but it framed their efforts with the language of heroism and quests. Many Magic players are happy to name their Magic heroes: former champions like Jon Finkel and Luis Scott-Vargas. But if you then ask if they’ve ever seen something heroic happen in a game, they balk.

What earns Magic pros the respect of their peers is, basically, good manners: treating opponents politely, signing cards and play mats for fans no matter how weird that feels, passing on knowledge to other players. Magic can be a complicated game, so new players are grateful for anyone who helps them crack the code. The world-saving scope of Magic’s fictional environment, it turned out, scaled down to the human proportions of being decent to the people around you.

Brad Nelson, a 33-year-old from Renton, Wash., generally acclaimed as the world’s best player in the Standard format, said: “At first the game was just metrics to me. If I gain X amount of clout, I can turn that into a writing gig with a website for supplementary income.” His perspective changed when he designed a deck called “Act 2” that some players used to qualify for an event on the Magic Pro Tour. A stranger on a Dublin street who had never qualified for a tournament before thanked him in tears, Nelson said. “That changed my perspective on the reach I have,” he recalled. He started thinking about what he could give to the game, not just what he could get from it.

Does offering a friendly word or holding the elevator door make you a hero? Or does that render the word “hero” meaningless? I wrote an entire book about Mister Rogers — a hero for many people — and learned that the foundation of his heroism was simply that he cared profoundly about the welfare of children and did everything he could to communicate that love to them. Not everybody can be Fred Rogers all the time, but if everybody indulged in an act of kindness two or three times a day, maybe we could be fostering an army of part-time heroes. Given its reach, could Magic help?

Claire Bao with cards she purchased at the event.

Claire Bao with cards she purchased at the event. On Saturday morning, 304 survivors returned to the Richmond convention hall, most of them young men. Jessica Estephan, the first woman to win a Magic Grand Prix tournament, confided that she used to walk into big tournaments like this, count the women competing and end up with maybe three, tops. Now? “I need more than two hands, and that just blows my mind and I love it.”

Andrew Cuneo, who has been playing Magic since its beginning, said: “When I started, it was almost entirely people who were college age, maybe a little bit of high school age. It’s still predominantly White guys, but it’s gotten broader, for sure.” (In June, Wizards confronted some of Magic’s cultural biases, permanently banning seven cards from tournament play, such as 1994’s Invoke Prejudice, because of racist content.)

Every round of the tournament, eight players were summoned to showcase tables so their matches could get broadcast on Twitch, via an array of 10 cameras. (Twitch, a live-streaming service, is owned by Amazon; Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.) Mythic Championships typically draw 500,000 to 750,000 unique viewers over a weekend, with a peak audience for tabletop matches around 25,000 to 30,000 watching at the same time. In an era of made-for-smartphone games like Fortnite and Hearthstone, Magic desperately needs not to be the old-fashioned 20th-century game that your parents played. So, striving to be streamer-friendly, Wizards recently launched a flashy online incarnation called Magic: The Gathering Arena. It planned to split the pro circuit between cardboard-based tournaments and silicon-based ones in 2020 (social distancing accelerated the pace of that transition, forcing everything online, at least for a while).

Concealed behind enormous black curtains was a TV production crew of over 30, divided into two control rooms, plus teams of commentators who worked in shifts, providing the humor and emotional swings that weren’t always apparent on the faces of two stoic young people playing a championship-level card game.

A casual game of Magic will likely contain a fair amount of trash talk and good-natured banter, but at the tournament, the top players operated in near silence, impassively flipping cards. This was partially because of a Bushido code where players tried not to show up their opponents, and partially because there’s an element of bluffing in Magic.

Lee lost two of his first three matches of the day. He was tired and distracted, he explained, having spent the previous night checking on news from Hong Kong instead of sleeping. The latest headline had been that a 16-year-old girl, allegedly gang-raped at a police station, went to a hospital to abort the resulting pregnancy. Even 8,000 miles away, Lee could feel his home falling apart.

Players’ fortunes rose and fell as the day progressed. By the final round, many of them had the hollow stares that come with utter mental exhaustion, as if they had just taken two SATs back-to-back, followed by the bar exam. Round 16 looked to be somewhat anticlimactic, because many of the leaders were far enough ahead of the field that they didn’t need to win.

Then there were murmurs and gasps from the spectators surrounding Table No. 1. Austin Bursavich, a 27-year-old from Houston wearing an Andrew Yang T-shirt, was at the top of the standings and would make the top eight after the match — win, lose or draw. His opponent, however, Paulo Vitor Damo da Rosa, was in fifth and needed a win or a draw. Damo da Rosa, a 32-year-old from Porto Alegre, Brazil, expected to be offered a draw and to move on to the top eight. But Bursavich announced that he wanted to play the game, shocking the crowd. Bursavich’s logic: He wanted to maximize his chances of winning the tournament, which would mean a $50,000 check and an invitation to the upcoming world championship. Since Damo da Rosa was not only the best player left in contention, but arguably the best player in the world, Bursavich reasoned that it behooved him to knock him out preemptively if he could.

“I personally wouldn’t have done it,” Damo da Rosa said with an expressive Brazilian shrug — but then admitted that many years earlier he had done it, attempting to clear a spot in the final eight for a friend who was on the bubble, and felt guilty about it afterward.

Damo da Rosa won the first game in quick order — at which point Bursavich surprised him again, by relenting and offering him the draw, which he quickly accepted. “I felt bad,” Bursavich said. “If I beat Paulo, it becomes a big story. He shouldn’t have any hard feelings. …” he reasoned. He trailed off, knowing that the aggressive maneuver hadn’t made him any friends. If you’re an unknown trying to take out a hero, then you have to be ready for people to think of you as a villain.

Judge Toby Elliott monitors players at the Mythic Championship tournament.

Judge Toby Elliott monitors players at the Mythic Championship tournament. On Sunday morning, most of the rows of tables were cleared to make room for a couple of large video screens that would broadcast the matches, placed far enough from the players that audience reactions wouldn’t tip them off about what card an opponent was holding.

Damo da Rosa defeated Cuneo. Bursavich, meanwhile, lost his own quarterfinal match, so he never got to test the wisdom of whether he should have tried to knock out Damo da Rosa.

The cheerful Brazilian advanced to the final, where he lost to the 24-year-old Ondrej Strasky — a Czech player who had periodically announced his retirement from Magic, always reconsidering after he did well at a tournament. Strasky told me that he would be heading home to Prague, where he planned to consume as much beer as possible. The victory in Richmond changed his plans for the next few years. “I’m going to play Magic full time,” he said, shocked by the turn in his fortunes.

In February, Strasky, Damo da Rosa and 14 other players competed for the Magic world championship at a tournament in Honolulu. Damo da Rosa won, giving him a legitimate claim to be one of the best Magic players ever. Weeks later, in-person Magic largely ended, both at the amateur level (most game shops closed) and at the professional level (gathering hundreds of people for a tournament seemed foolhardy); the game migrated, at least temporarily, online.

As covid-19 permeated American society, new ideas about who qualified as a hero took hold. Medical workers, risking their lives to treat the ill despite a conscience-shocking shortage of masks and other personal protective equipment, seemed like obvious candidates for hero status. In cities around the world, the quarantined population opened their windows every night and sang or banged on pans, celebrating doctors, nurses and other first responders.

Lee Shi Tian of Hong Kong is a Hall of Fame player and is active in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. “What I’m trying to do is use my name in the gaming industry to tell people what is happening in Hong Kong.”

Lee Shi Tian of Hong Kong is a Hall of Fame player and is active in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. “What I’m trying to do is use my name in the gaming industry to tell people what is happening in Hong Kong.” Soon enough, people pointed out that our pandemic heroes included grocery-store workers, delivery people and anyone else who needed to leave the house to do their jobs. Heroes are people who do what other people can’t — but calling underpaid workers heroes sometimes looked like a way to avoid paying them or getting them sufficient PPE gear instead of taking inspiration from them.

I checked in with Lee back in Hong Kong, where masks and aggressive social distancing had helped get the coronavirus under control. He had been playing in online Magic tournaments, although he was suffering from time-zone issues, struggling to stay sharp in competitions that began at midnight Hong Kong time.

In Hong Kong politics, he was particularly concerned about the new extradition laws sponsored by China: “a new wave of protesting has been formed and lots of Hong Kongers are in the fear of a repetition of what happened in Uighur,” he wrote in an email, referring to the concentration camps now holding as many as a million Chinese Muslims. Similarly, in the United States, thousands of protesters, many in masks, took to the streets, risking their health in the hopes that they might save their democracy. Doing the right thing seemed more important than ever — that could be loud and dramatic, or it could mean staying home and being kind to the people around you.

For me, the heroism of Magic seemed more meaningful every day: not the grand mythic gestures, but the accumulated moments of courtesy and decency, and the knowledge of the players that they were part of a subculture — which was another word for a society. As the pandemic wore on, and then the protests sprung up after the killing of George Floyd, I found myself feeling differently about larger-than-life heroes, and not just because so many revered men had proved to be so flawed. I wanted a world where untold millions of people did heroic things, and I hoped that desire wasn’t just a childish longing for magic.

Gavin Edwards, the author of books including “Kindness and Wonder: Why Mister Rogers Matters Now More Than Ever” and “The Tao of Bill Murray: Real-Life Stories of Joy, Enlightenment, and Party Crashing,” lives in Charlotte.

Designed by Twila Waddy. Photo editing by Dudley M. Brooks