Stokely Carmichael didn’t deserve Bill Clinton’s swipe during John Lewis’s funeral

The speakers extolled Lewis’s virtues as a person. They honored his civil rights sacrifices. And they celebrated his political accomplishments. Between remembrances, singer Jennifer Holliday offered soul-stirring renditions of gospel classics, including King’s personal favorite, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.”

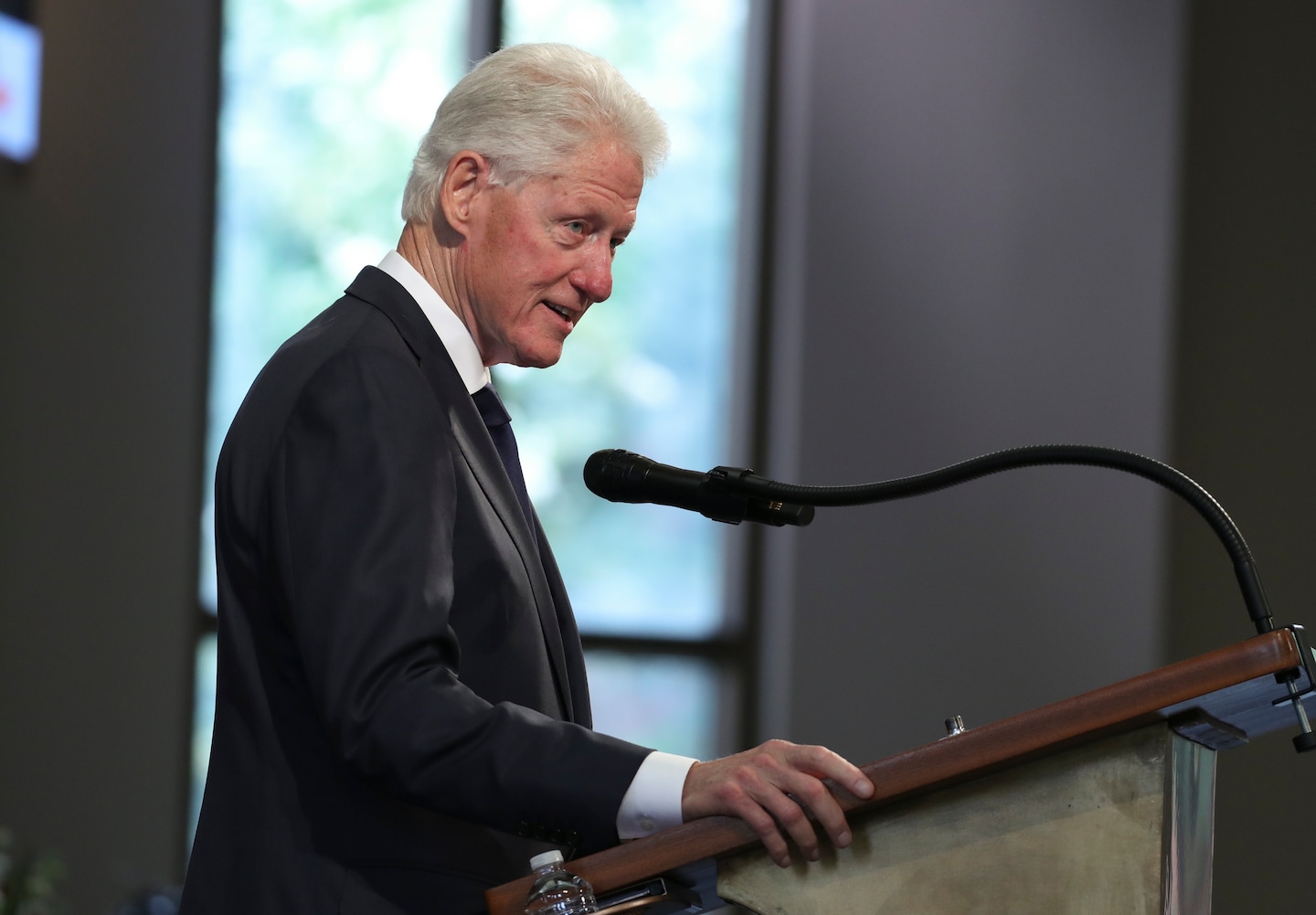

I was very much enjoying the service, eagerly anticipating former president Barack Obama’s eulogy, when former president Bill Clinton, halfway through a warm, folksy tribute to Lewis, needlessly attacked another civil rights activist — Kwame Ture, better known by his birth name, Stokely Carmichael.

Carmichael was Lewis’s successor as the chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Born in Trinidad and raised in the Bronx, he introduced the nation to Black Power during James Meredith’s 1966 March Against Fear.

Clinton’s attack was more subtle than savage. But it was still severe.

“There were two or three years there where the movement went a little too far toward Stokely,” he said, “but in the end, John Lewis prevailed.”

For Clinton, the movement’s problematic drift was its turn toward Black Power. Black Power was an approach to change rooted in Black political independence, economic empowerment and cultural pride that gained popularity during the late 1960s.

Like many White liberals and progressives, Clinton doesn’t view Black Power as a logical extension of civil rights organizing. He doesn’t see it as a natural outgrowth of movement victories in the South that put the ballot in Black hands. And he doesn’t recognize it as a product of Black frustration with the slow pace of progress in the North.

He sees it instead as an unfortunate break from nonviolence and a regrettable rejection of integration.

Clinton’s remarks were disappointing but not surprising. Soon after Carmichael called for Black Power, a chorus of left-leaning voices denounced him as the prophet of rage and the high priest of hate. This criticism has never abated. Instead, it has been bolstered by historians who take a dim view of activists who embraced racial solidarity and reinforced by cultural influencers who share the same negative perspective.

This mischaracterization of Carmichael serves a purpose. It allows people to dismiss his critique of America.

Carmichael believed that racial inequality was fundamentally a political and economic problem. Achieving racial equality, therefore, required a radical transformation of American politics and economics.

Unlike Lewis and other adherents to philosophical nonviolence, Carmichael did not believe that racism was principally a moral dilemma. Love, therefore, would not be enough to protect Black ballots, provide Black children with the education they deserved, lift Black people out of poverty or stop racial terrorism.

Dismissing Carmichael allows people to ignore systemic racism and to emphasize instead individual prejudicial behavior. But the solution to ending police violence in Selma in 1965 wasn’t simply removing Dallas County, Ala., Sheriff Jim Clark. To be sure, personnel had to change, but so too did the culture and practice of policing, as well as the priorities of the criminal justice system. The “bad apple” theory of police misconduct was as false then as it is now.

Beyond marginalizing structural analyses, misrepresenting Carmichael distorts his life and legacy.

Carmichael was a master organizer. In 1965, he shepherded into being the original Black Panther Party, a radically democratic, all-Black political party in Lowndes County, Ala. He was also a brilliant political theoretician, responsible for breathing life into Black Power.

Carmichael preceded Lewis in death by some 20 years. And like his SNCC comrade, he also got into some “good trouble” during and after the movement. Too often, though, we don’t think of his activism as such. We brush it aside as pointless rabble-rousing.

Disparaging Carmichael also warps civil rights history. The narrative that flows from this viewpoint overemphasizes King, overstates white participation, overlooks self-defense and overestimates federal support. In addition, it makes it hard to see the ways that civil rights and Black Power inform today’s Black Lives Matter protests.

America is experiencing a racial justice reckoning the likes of which we haven’t seen since the 1960s. Perhaps if the movement had gone a little further “toward Stokely” back then and addressed systemic racism, there would be no need for people to take to the streets today.

Maybe this time, if Carmichael “prevails,” things will be different.

Read more: