A pregnant woman with covid-19 was dying. With one decision, her doctors saved three lives.

On a bright October day last fall, Ebony Brown-Olaseinde and her husband, Segun Olaseinde, found out that their longtime dream had finally been realized: They were going to be parents. After three years spent trying to conceive, they had succeeded through in vitro fertilization — and they soon learned that their twins, a boy and a girl, were due in June 2020.

By the beginning of March, Ebony, 40, an accountant in Newark, was feeling grateful that her high-risk pregnancy had progressed so easily. Segun, 43, an operations manager for UPS, couldn’t wait to be a father. Ebony’s doctors told the couple that she’d reached an important milestone: At 24 weeks pregnant, their twins were viable, more likely to survive if they arrived early.

That was one week before the World Health Organization formally declared the coronavirus pandemic. Ten days after that, Ebony suddenly began feeling short of breath.

The following excerpts from interviews with Ebony, her family and members of the medical team that cared for her at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, N.J., have been edited for length and clarity.

The decision to do an emergency Caesarean section likely saved the lives of Ebony Brown-Olaseinde, who was battling the coronavirus, and her babies. (John O’Boyle/Saint Barnabas Medical Center)

The decision to do an emergency Caesarean section likely saved the lives of Ebony Brown-Olaseinde, who was battling the coronavirus, and her babies. (John O’Boyle/Saint Barnabas Medical Center) Ebony Brown-Olaseinde: At first, we were told that if you were sick, then you needed to wear a mask, but if you didn’t have a cough or a fever, you were fine. I wasn’t around anybody who seemed to have covid. But I did continue to go to work in March.

Fariborz Rezai, director of critical care and medical/surgical intensive care: The first ICU covid patient we had was March 13; I remember because I was on call that weekend. And then they just kept coming.

Brown-Olaseinde: Now that I look back and I know all of the symptoms, I probably was sick earlier than I knew. I never had a fever, I never had a cough, but I did have a runny nose that I attributed to it being cold in my office. I remember, on March 22, I was folding clothes and felt a little winded. I remember needing to sit down. But I figured, “I’m seven months pregnant with twins.” I went to work the next day, and had a small meeting — we social distanced — and I remember not being able to breathe well in that meeting. By 10 o’clock I remember going to my office and emailing my supervisor to say, “I’m not feeling well, I’m going to go to the hospital, I’ll see you guys tomorrow.” My OB/GYN advised me to go to Saint Barnabas, and when I got to the parking lot I called my husband and let him know that I was going to go to the hospital to see what the problem was. They got me in, they gave me IV fluids, and I texted my husband at 5 p.m. to say, “I’m feeling better, I’ll be home by 6 o’clock.” But then the nurse came back and said that test results showed I didn’t have the flu, and they wanted to do X-rays on my lungs. When we got those results back, the nurse said it didn’t look good.

Angela Wimmer, OB/GYN: Ebony never thought she was covid-positive when she came to the hospital. She told me she just didn’t feel great. She was shocked that she had it.

Brown-Olaseinde: They put me on oxygen, and two days later, the test came back confirming that I did have covid. I wasn’t able to maintain the oxygen level that they needed me to maintain for the twins. They’d come in and check the twins every couple of hours. They wanted to put me on the CPAP machine, and the CPAP machine is really scary. When they put that on, I felt like I couldn’t breathe. The doctor said, “Listen, you’re going to go and get intubated,” and I remember saying to him, “Please, just don’t take the babies out. Please, let them mature more.”

Segun Olaseinde, Ebony’s husband: I took time off work and self-quarantined, because we needed to see if I had covid. I was staying home, waiting for calls from the hospital. I was praying a lot, calling family members, our family members were praying. When she called and said they were going to put her on the ventilator, she was more calm than I was. I started crying.

Brown-Olaseinde: I called my husband, I gave him the phone numbers of people to reach at the hospital if something happened. I remember telling my husband, “If I don’t make it, just make sure you take care of the babies.” And then that’s all I remember.

Wimmer: She tried to hold off on being intubated because she just wanted the best for her babies. That’s what she kept saying: “Just let them make it.”

Richard C. Miller, chairman of obstetrics and gynecology: On March 31, at 28 weeks and one day into her pregnancy, Ebony was having more respiratory difficulties than we thought we’d be able to amend. Her blood pressure began to become very erratic, and very low.

Olaseinde: It got to the point where I was so on edge I couldn’t really take phone calls anymore, so I called my sister. She’s a doctor, so any communications from the hospital went through her and she would call me, because I wasn’t in a state of mind to process medical terms.

Yetunde Daniel, Olaseinde’s sister: As a physician, knowing what I know, I was scared and worried for Ebony. This was my sister-in-law, who I love. But I had to be positive and not share too many details that would only worry my brother more. The worst-case scenario would play in his head, and he was at home alone by himself. We couldn’t even be there for him.

Rezai: I vividly remember, it was around noon that day, and I walked by her room and the nurse said, “Hey, Dr. Rezai, she’s getting worse.” Her blood pressure was going down, and she became more and more hypoxic, meaning her oxygen was dropping. We had no more room to give her any more oxygen. At that point, Dr. Miller and I spoke about what to do.

Miller: There are some cases of women who have severe respiratory failure who do respond and turn a corner, but it’s always a 50/50 proposition. The options at that point would have been to wait to see if Ebony succumbed to her disease, and then do a postmortem Caesarean section. Those are always much more difficult. The babies’ condition would be much more dicey.

Rezai: That’s when we made the call to get everyone into the room for an emergency C-section.

Before the C-section, the team mobilized to turn the intensive care unit into a makeshift operating room. (Saint Barnabas Medical Center)

Before the C-section, the team mobilized to turn the intensive care unit into a makeshift operating room. (Saint Barnabas Medical Center) Miller: We’d already sounded the alarm that we might be moving Ebony from the intensive care unit over to the operating room, but in fact she deteriorated so rapidly and profoundly that there wasn’t time to move her. The OR brought over all the equipment; they essentially mobilized an operating room and set it up for us in the ICU.

Rezai: Suddenly everybody is there. We’re talking 20-plus people. And this is not the largest room; it’s actually very small.

Miller: The delivery itself was probably the most risky type of procedure for the individuals who were in the room to do the C-section. First of all, it was done in intensive care, not in our regular operating room; and second of all, Ebony was covid-positive and considered to be highly infectious.

Wimmer: That was the craziest day of my career. I’ve been practicing for about 22 years, and I’ve done urgent, emergency C-sections, but never in an ICU setting. All morning, we were checking in on Ebony, we’re watching her oxygen and her blood pressure drop as they’re increasing her pressure support, and I thought, “Oh my God, she is not going to survive.” And then my next thought was, “Oh my God, we have to get these babies out.” The faster we could get in and the faster we could get out was the best for those babies and for Ebony. We needed her to turn that corner.

Brianna Carlotti, critical care nurse: Ebony was sedated and in and out of consciousness. Her eyes would open but then immediately close. I was at the head of the bed with her the whole time. I was holding her hand, and telling her, “We’re going to deliver your babies, they’re going to be okay. We need you to hang on. You’re going to be better.” She was my priority.

Miller: The babies came out so quickly.

Rezai: Five minutes, at most. One and the other right after.

Kwanchai Chan, neonatologist: We had two teams in the room, and respiratory therapists. Twin A, Jurnee, was 2 pounds, 0.6 ounces. Twin B, Jordan, was 2 pounds, 5 ounces. They were premature, and they needed to be intubated, but they did well. They were stable.

Carlotti: There was a lot of hustle and bustle in the room. And then it was over, and everyone got out, and it was just me and Ebony. I was getting her cleaned up and telling her she did such a good job. That is a day I will never forget.

The team cares for the babies post-delivery in the ICU. (Saint Barnabas Medical Center)

The team cares for the babies post-delivery in the ICU. (Saint Barnabas Medical Center) Olaseinde: The doctors called my sister, and she called me. They told her there was the possibility that they were going to take the babies out. And then, as she was telling me this, they called her back and said the babies were out already. I was freaking out, because that was so early. But I talked to family members who knew people who had preemie babies, and they were telling me the twins were going to be okay.

Rezai: As soon as the OR team and the NICU team left, in the next hour or two, Ebony’s pressure requirements — the amount of medication required to keep up her blood pressure — started improving. Her oxygen requirements started improving. By the next day, she was a new person. And about 48 hours after the C-section, we had her off the ventilator. It was pretty astonishing. I’ve been a critical care physician for over 13 years, and I’ve never seen anything like that. Especially with covid patients, you know when a patient is going to survive or not, and Ebony was not looking like she was going to survive. The decision to do the C-section really saved her life.

Daniel: What they did was astounding. If they’d waited another 30 minutes, what could have happened? If they had wasted any time at all, this would be a different story. Especially as an African American woman, that she had such a good outcome in a case like this — that’s a miracle.

Brown-Olaseinde: When I woke up on April 3, I thought I’d only been there for a week, but I’d already been there for two weeks.

Carlotti: She was out of it in the beginning, and it was hard to explain to her: “You came in with these babies, and you don’t remember having them, but they’re here and they’re doing well.” I’d tell her, and she’d touch her stomach, and I’d say, “They’re safe, they’re doing well.” Then she’d go to sleep and wake up confused again.

Brown-Olaseinde: My husband told me that the babies were born. The doctors had told me, but I wasn’t very responsive yet, and I didn’t remember that. My husband and sister-in-law were able to send a little picture of the twins, and I’d look at the picture every day. I remember asking the nurse, “Can I go home?” Because I thought as soon as I go home, I can see the twins.

Chan: Ebony had to have two negative covid tests to come to the NICU, and it took her about a month to achieve that. But her husband never tested positive, so we allowed him to come in.

Olaseinde: The first time I saw the babies, all I remember is how small they were.

Brown-Olaseinde: I came home on April 9. I still had to be isolated from my husband because I was testing positive. It was difficult. I was just coming back from being on a ventilator, I still couldn’t really breathe, my voice was gone, I had to stay in our bedroom. I’m thankful that my husband was able to have the month off because he was able to take care of me every day, and he was still able to go see the twins every day. He would FaceTime from the NICU, he’d set the phone on the incubator, and I could look at them, and read to them, talk to them.

Chan: When Ebony finally could come to see the babies, we tried to make it up to her. We had a banner, we had a little celebration for her. She’d waited so long.

Brown-Olaseinde: The nurses were so lovely. They actually had made a sign that said, “Welcome, Mommy, we miss you.” It became emotional. When I got there, I was like, “Oh, my” — it didn’t translate over the phone just how small they were. As a mother I didn’t care, that first day I was just holding them. But it was intimidating, because they were so fragile.

Chan: Jurnee left after 53 days, and that was emotional for Ebony because I think both parents preferred to bring home both babies together, but unfortunately for Jordan, he still needed some oxygen. So we kept Jordan approximately another week. He went home on June 1.

The first time Jurnee and Jordan Olaseinde met each other in the NICU after being apart for more than a month. (Ebony Brown-Olaseinde)

Members of the medical team that cared for Ebony Brown-Olaseinde and her twins gathered to send her off, clapping as she left the hospital with her babies. She thanked the staff for saving their lives. (Saint Barnabas Medical Center)

LEFT: The first time Jurnee and Jordan Olaseinde met each other in the NICU after being apart for more than a month. (Ebony Brown-Olaseinde) RIGHT: Members of the medical team that cared for Ebony Brown-Olaseinde and her twins gathered to send her off, clapping as she left the hospital with her babies. She thanked the staff for saving their lives. (Saint Barnabas Medical Center)

Wimmer: That was a time when the ICU was really spiraling. Patients weren’t doing well. And so for Ebony to pull off a miracle, it was incredible for all of us. We were so elated for the family.

Brown-Olaseinde: The team saved our lives. They really did. I’m happy they made that decision to take the babies out, even though I was so adamant about letting them grow more inside.

Miller: The fact that she was unconscious when she delivered her babies, only to wake up to know that they had been delivered — those are substantial, impactful events for her. She’ll never be able to fill in all the gaps. But I’m sure she’ll never forget the beginning and the end of the journey here.

Brown-Olaseinde: I still am short of breath, so that’s a process. I do have some pain sometimes in my side. I have a follow-up appointment with a cardiologist in a couple of months. I received hydroxychloroquine, and every day I still think about that. I watch the news, and I see the side effects, and I don’t know what the consequences are going to be from taking that medicine.

Rezai: Some patients do suffer post-traumatic stress. So that’s something you have to be attuned to. I’m sure she’s very happy and ecstatic that she survived, that her babies are healthy. I’m not a psychiatrist, and everyone is different, but we do recognize that PTSD among ICU survivors is very real.

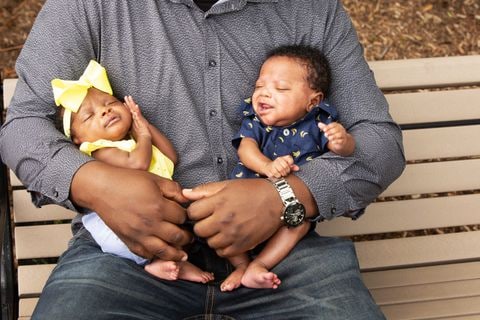

Brown-Olaseinde: The twins are beautiful. They make us laugh so much, they make us smile. They’re growing well, they’re doing tummy time well, they’re focusing well. As the doctor said, because they were preemies, they’ll be a little bit delayed, but they’re on point for preemies. And I’m so happy they made it. I’m just so happy they made it.

“The twins are beautiful. They make us laugh so much, they make us smile,” Ebony Brown-Olaseinde said. (John O’Boyle/Saint Barnabas Medical Center)

“The twins are beautiful. They make us laugh so much, they make us smile,” Ebony Brown-Olaseinde said. (John O’Boyle/Saint Barnabas Medical Center) Photo editing by Monique Woo. Design by Audrey Valbuena. Copy editing by Annabeth Carlson.

Read More:

Four women on being pregnant in a time of uncertainty and upheaval

Her pregnancy was already high risk. Then she gave birth on a ventilator.