What Lacy Clay’s primary loss reminds us about generational house-cleanings

Lacy Clay is now 64, having added two decades to his father’s long reign over Missouri’s 1st Congressional District. Change, a dirty word around the House of Clay, finally arrived on Tuesday — a mighty gust by the name of Cori Bush, who beat Clay for the Democratic nomination.

Bush is a nurse and single mother who came to politics by way of protest. She marched in the streets of Ferguson, a St. Louis suburb, in 2014 after a police officer shot a young man named Michael Brown. She did not stop. Her 2018 challenge to Clay fell short; Bush just kept running.

When a machine as sturdy as the Clay operation conks out, it’s generally a sign that someone became a bit too comfortable. Membership in Congress is an endless campaign: There’s always another election looming. Most close observers of Lacy Clay would agree that he probably underestimated the danger posed by a dynamic foe with a sharp agenda.

But Bush is also riding a wave of political energy from the leftward frontier of the Democratic Party. She did to Clay what Jamaal Bowman did to 16-term Rep. Eliot L. Engel (D-N.Y.) of the Bronx last month; what Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did to 10-term then-Rep. Joe Crowley (D-N.Y.) of Queens in 2018. A new generation of Democrats is not content to wait in line for seats that somehow never open up. They are making their own openings.

One need not share their politics to appreciate the appeal of these energetic progressives. American government has not exactly cloaked itself in glory the past few decades. Issues such as racial justice, economic opportunity and environmental stewardship are far from new, yet far from solved. Folks have lost patience. They’re ready for a fresh team on the field.

Generational house-cleanings are a recurring feature of American politics, where nothing is forever. (Except maybe Michigan’s Dingell Dynasty. Every Congress since 1933 has included a Dingell from the suburbs of Detroit — father John, son John Jr. and now John Jr.’s widow, Rep. Debbie Dingell (D). Having won her primary, she appears certain to keep the streak going.) Americans of a certain age will remember the young veterans of World War II, of whom John F. Kennedy said “a torch has been passed to a new generation.” The “Watergate generation” of reformist Democrats rolled into Washington around 1975, followed by Reagan revolutionaries on the right.

The current uprising highlights an intellectual flabbiness among moderates, of whom Clay, Engel and Crowley are all rather tired examples. To be moderate in today’s politics has become an indictment — in both major parties. Moderates supposedly lack passion, don’t care, won’t fight and, therefore, can’t win.

It hasn’t always been thus. Moderation has often been on the leading edge of philosophy. Aristotle, in his “Nicomachean Ethics,” argued that every human virtue lies at the center point between some deficiency and some excess. The ideal political liberty, for example, will be found midway between no freedom and unlimited freedom. The German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel spoke of political “dialectics,” in which opposites — the “thesis” and its “antithesis” — are resolved into a “synthesis.” In religion, John Henry Newman developed (for a time) a theology of the “via media,” or middle way.

That spirit animated U.S. politics around the turn of the century. Bill Clinton, with his New Democrat movement, extolled midway solutions to political stalemates. From the GOP came an echo in the “compassionate conservatism” of George W. Bush. Barack Obama sounded distinctly Hegelian when he preached: “There is not a liberal America and a conservative America — there is the United States of America.”

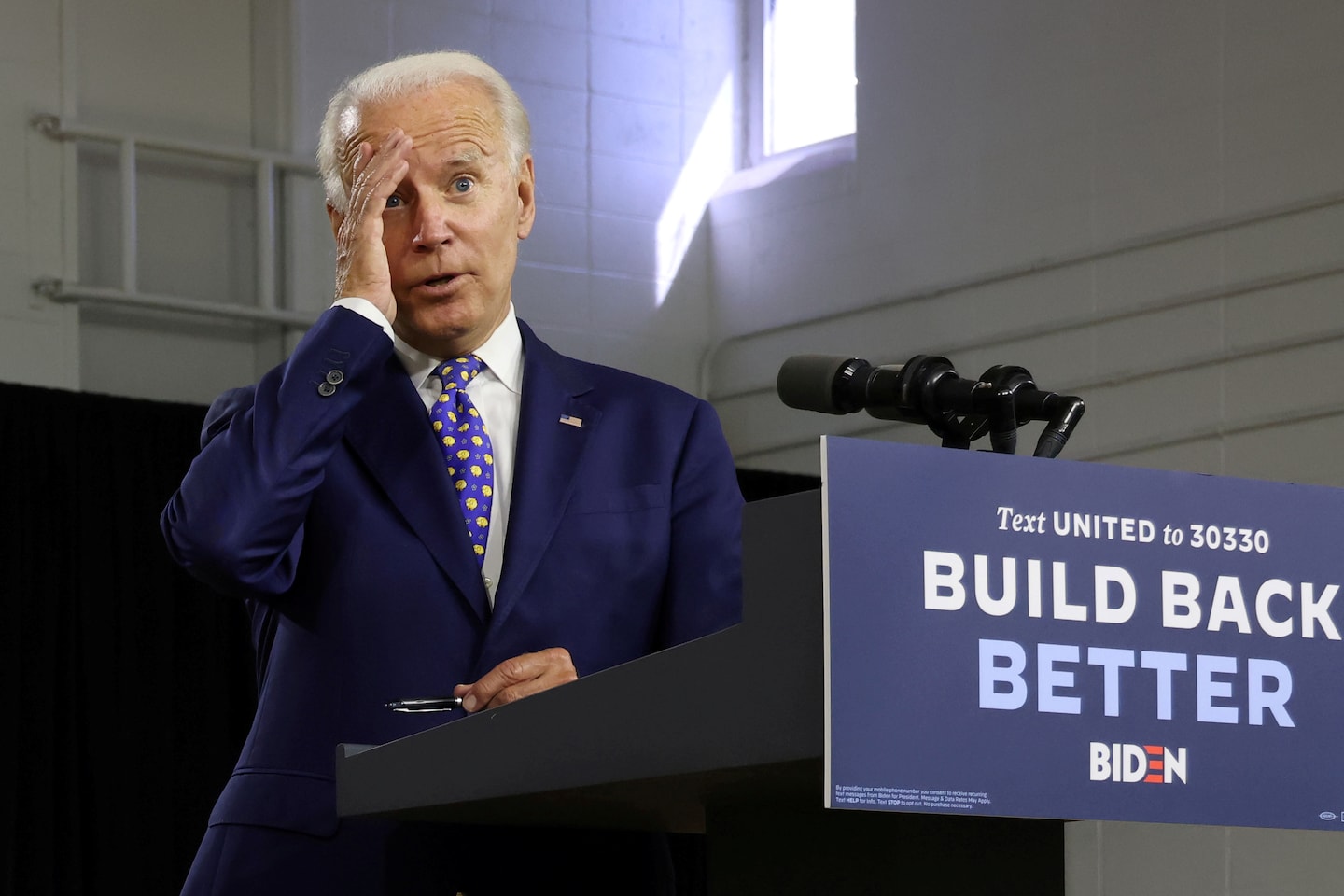

No such energy animates moderation today. The passion in politics comes from the extremes, heated over the flames of social media and cable television. Today’s most prominent moderate, Joe Biden, offers moderation as a salve rather than a solution — a balm to cool the body politic after four years of Trumpian abrasion.

Moderation lives or dies by results, and, frankly, we moderates have under-delivered. The middle class has not grown. Health care is not cheaper. Liberal democracy has not triumphed around the world. Yet, given the dangerous polarization of contemporary politics, now’s not the time to assume that moderates will always have a seat at the table. We’ve got to work for it.

Read more: