Why Mass Incarceration Is Looming as a Campaign Issue: QuickTake

1. Just how big is the issue?

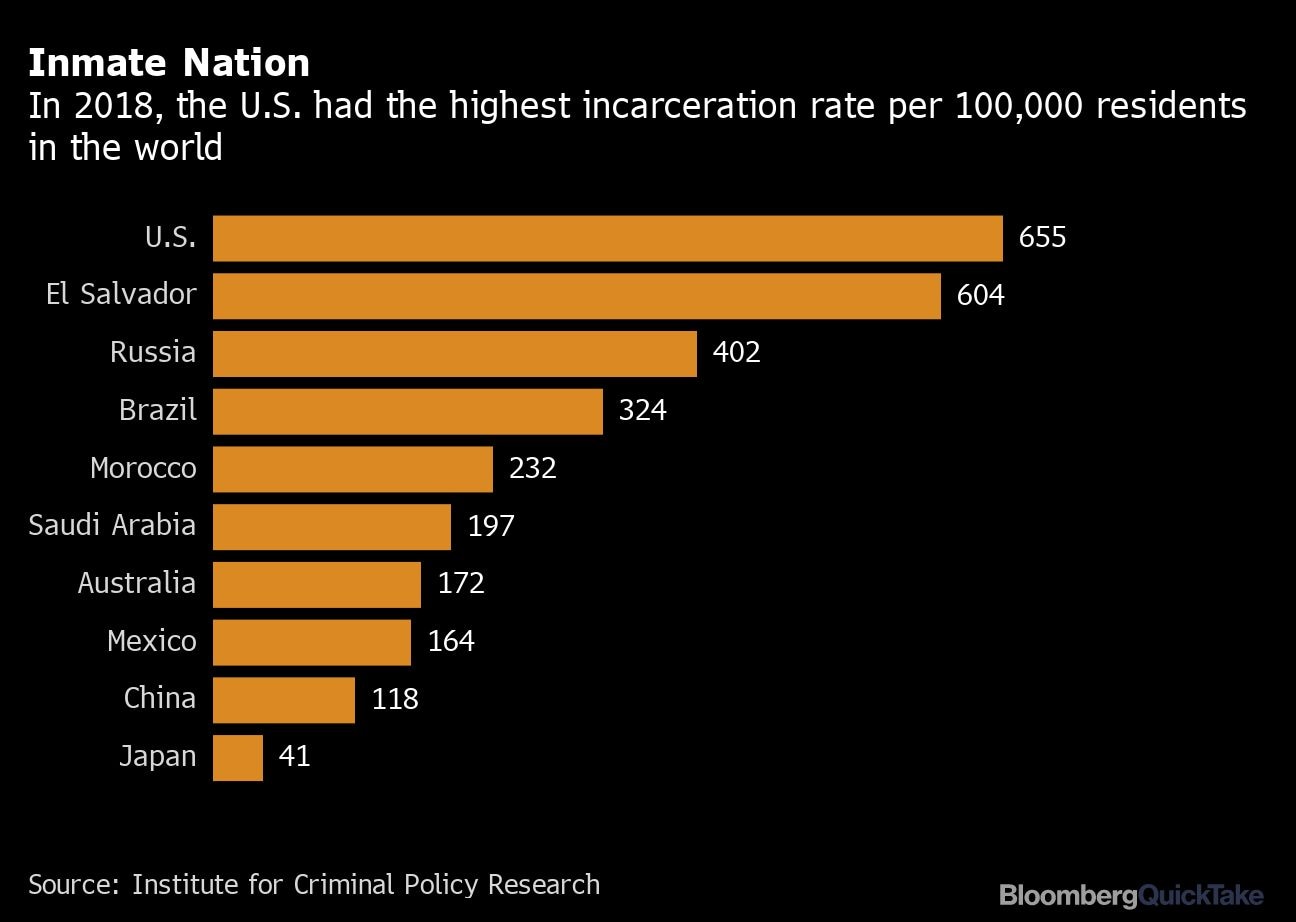

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the number of prisoners in U.S. state and federal institutions peaked in 2009 at 1.6 million. In 1960, that number had been 210,000; by 1990 it had jumped to about 775,000. It’s declined slightly in recent years, falling to 1.5 million people in 2018. However, counting people in local jails and detention centers, the number of people behind bars jumps to 2.3 million, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. The U.S. outranks all other nations both in total number of prisoners and rates of incarceration. The U.S. locks up 655 people for every 100,000, compared with 402 in Russia and 118 in China, according to the Institute for Criminal Policy Research.

2. Where does the term come from?

It was first cited in the criminal justice debate by David Garland, a professor at the NYU School of Law. He and other prison reform advocates used it, or mass imprisonment, to denote not only unusually large numbers of people behind bars, but a systematic imprisonment of groups within society. Criminal justice advocates connect the surge in prison populations to America’s history of racial injustice, pointing to the disproportionate numbers of Black Americans locked up.

3. How did we get here?

A wave of violent crime in the 1960s in cities with declining populations and crumbling tax bases ushered in a “law-and-order” approach to criminal justice policy. Many of these changes were pushed most fervently by Republicans. In the 1970s, President Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs, and states adopted tougher sentencing laws. In the 1980s, with crime still high, many states reduced the level of discretion judges had to set sentences; mandatory minimums for federal drug charges were introduced, along with changes that required offenders to serve more of their sentences. President Ronald Reagan bolstered strict drug laws with the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. In the 1990s, after losing three presidential elections in a row, Democrats sought to show that they were also tough on crime.

4. What was Biden’s role?

In 1994, as a U.S. senator from Delaware, Biden co-authored a sweeping crime bill that provided funding for the hiring of 100,000 new police officers and allocated nearly $10 billion in prison funding. Crime did begin to fall across the country, for reasons that are still hotly debated, but incarceration rates continued to rise, driven by things like “three strikes” laws that mandated lengthy or even life sentences for repeat offenders.

5. How have minorities been affected?

The era of mass incarceration has put Black, and increasingly, Hispanic, Americans behind bars in disproportionate numbers. Despite making up 13% of the U.S. population, African Americans represent 33% of state and federal prisoners, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. There are 12 states where African Americans make up more than half of the prison population, the Sentencing Project reports. Harsh drug laws contributed to the disparities in African American and white experiences in jails and prisons. Four years after the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, the average federal drug sentence was 49% higher for African Americans than for whites due in large part to the introduction of mandatory minimums for crack cocaine offenses.

6. What have critics said about the mass incarceration?

Opponents of the 1994 crime bill called it a terrible mistake, saying it increased prison populations unnecessarily, helped lead to the so-called militarization of police departments and diverted state funding away from community programs and public education and into the prison system. In 2010, Michelle Alexander, a law professor and civil rights activist, published her book, “The New Jim Crow,” which linked the large numbers of imprisoned Black Americans to historical patterns of racial discrimination. After that, the progressive wing of the Democratic Party became more vocal in pushing for a fundamental reshaping of what was labeled “the prison-industrial complex.”

7. What’s been happening?

In recent years, some conservatives have also become convinced that the country is locking up too many people. In part that had to do with the cost, which was falling heavily on states. By one estimate, prisons alone cost U.S. taxpayers $80 billion every year. In 2018, a bipartisan bill passed Congress and was signed by Trump that granted judges more discretion in sentencing and boosted efforts for prisoner rehabilitation. The push to legalize or decriminalize marijuana use has also been linked to the push for racial justice in the criminal justice system: Black people are 3.6 times more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana possession despite evidence that they use the drug at similar rates. Even the coronavirus pandemic has sparked debate about the role of incarceration and the potential for early release for non-violent offenders.

8. How has this become a campaign issue?

Trump has seized on Biden’s role in the 1994 crime bill, running an ad titled “Joe Biden has destroyed millions of Black American lives,” that argues that policies Biden supported have “put hundreds of thousands behind bars for minor offenses.” At the same time, however, Trump has branded himself as a law-and-order president keen on protecting police officers and denouncing protesters against police brutality as thugs.

9. What does Biden say?

He responded to Trump by releasing his criminal justice campaign platform, which includes reducing the number of people incarcerated and ridding the justice system of racial disparities while driving down crime. Biden’s pick for a vice presidential running mate, Senator Kamala Harris, was a prosecutor and California’s attorney general earlier in her career. During her own run for the presidential nomination, she was criticized by supporters of more progressive candidates as having contributed to the problem of mass incarceration. But since protests over the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer began in May, she has been a leading voice in calling for police reform, including co-authoring a Senate bill to ban police use of chokeholds.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.