How the media has us thinking all wrong about the coronavirus

Researchers have documented our preference for the unexpected, exploring how information that is “surprising” provides greater entertainment and attracts more attention. Often this is benign: A basketball game that ends in a stunning upset, for instance, gets more coverage than a routine blowout. When it comes to covid-19, however, this preference — and the media’s tendency to indulge it — presents a real danger. It warps our thinking about the pandemic and may be leading us toward irrational decisions that can cause lasting harm.

The problem is that reporting on covid-19 tends to follow the shark-attack example. We’re unaccustomed to what the virus has wrought — hospitals overwhelmed, celebrities and world leaders suffering near-death experiences in the public eye. These “surprises” are what the media focuses on. The challenge with the novel coronavirus, however, is exactly that: It’s completely novel. Nothing about it should be expected. All of the ways it behaves — and doesn’t behave — are new. In that sense, a nursing home with zero infections should be just as newsworthy as a nursing home with several.

Because of the overwhelming bias in what gets reported about covid-19, the public lacks essential context for making reasoned, well-informed decisions. Researchers found, for example, that droplets containing the virus can, in theory, travel far in the air. That discovery was widely reported. Overlooked was the fact that, even if droplets can travel far in the air, we don’t have evidence that they usually do. So hiking trails and other open-air facilities were closed, despite the fact there are no documented cases of covid-19 caused by hiking.

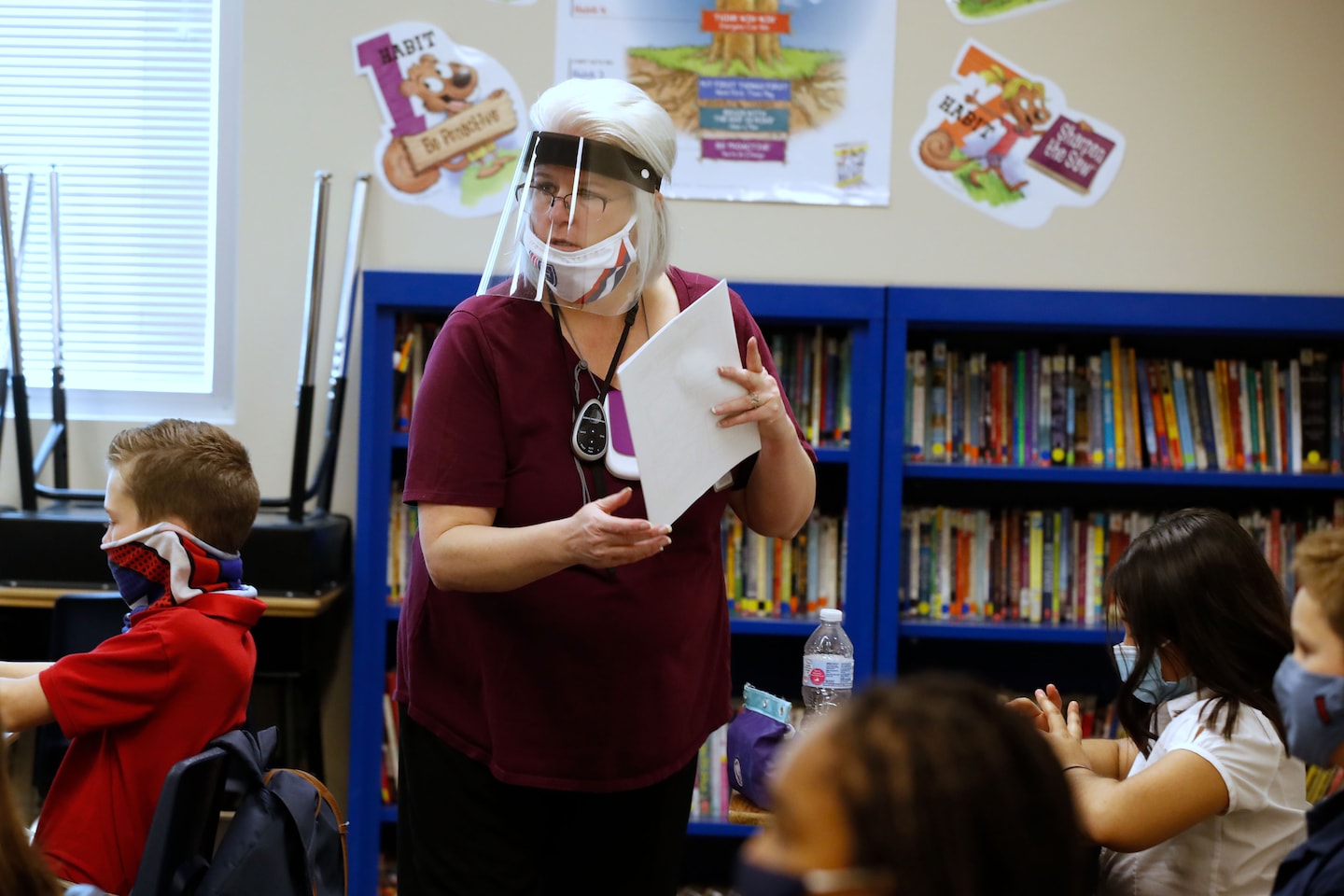

Then there is the debate surrounding schools. Districts in many areas are still grappling with whether to reopen, or when and how, with plenty of accompanying media coverage. Nearly all of it focuses on examples of covid-19 infections. But the uncertainty surrounding the coronavirus means the same attention should be given to schools where there are no cases. Twitter is full of people saying, “My kid’s school opened without any cases this week!” Data I’ve collected shows that there are many camps and child-care facilities — even large ones — operating without any confirmed cases. These examples are out there; they just don’t show up in headlines.

Parents and policymakers influenced by this skewed reporting may naturally conclude that any in-person instruction is dangerous. But they are missing a key piece of the puzzle. There are 291 school districts in Indiana serving 1 million children. Several have been open since July. Even if, by one count, there have been 100 cases in Indiana schools so far, this is likely to be a low in-school infection rate. Beyond that, this fact doesn’t tell us anything about whether infections spread in schools.

In the absence of complete information on risks, our overreactions can have serious consequences. One example is the Three Mile Island nuclear event, which has not been conclusively linked to any long-term negative health outcomes but did terrify Americans about nuclear power. People simply didn’t have enough baseline information about the number of nuclear plants operating safely on a given day to realize that the probability of a nuclear disaster was vanishingly small. The result was that nuclear power — a plentiful, carbon-free energy source — never reached its potential in the United States, leading to needless overreliance on dangerous fossil fuels.

We risk making similar mistakes with the coronavirus. Keeping children out of school harms their development. Shuttering businesses destroys livelihoods. These downsides may be offset by the benefits of limiting covid-19. But we cannot rationally assess the trade-offs when we have only partial information.

What we really need to know is not the anecdotes that news reports provide, but the full picture. What share of schools have cases? Moreover, what differentiates places with cases from those without? Is it differences in prevention measures? Demographic and economic characteristics? The prevalence of community-spread events?

To answer these questions, we need systematic data collection and reporting — the sort that lets us evaluate risks in all kinds of situations, from driving cars to flying on planes to, yes, ocean swimming. It should be possible to do this. As schools open, districts will have counts of at least detected covid-19 cases, as well as information on the overall enrolled population. This data could be combined in public databases with user-friendly dashboards and maps. Since this type of data collection has not been spearheaded by central authorities, I’ve partnered with a set of national educational organizations and a data team to try to put it together.

Once we have a dashboard for these data, the media could use these sources to drive their coverage. Even if they chose not to — because “Day 45 with infection rate below 0.01 percent” doesn’t generate a lot of clicks — citizens would be empowered to analyze the relevant information themselves.

With data like this widely available, we could make good — or at least better — choices about who should open and when.

Watch Opinions videos:

Read more: