What does baseball sound like during a pandemic? Loneliness, and hope.

It is the sound of anticipation.

But in the blazing sunlight of afternoon, right at first pitch, the same near silence is now a grotesquerie. “Play ball!” the umpire yells as if he’s right in your ear. The announcer introduces the visitors’ leadoff hitter to an official crowd of zero. Your precious secret suddenly feels like a conspiracy theory — even as you choose to accept it, you are aware of the deceit it contains.

Then you notice the soft buzz of a fake crowd piped in over the loudspeakers.

It is the sound of loneliness.

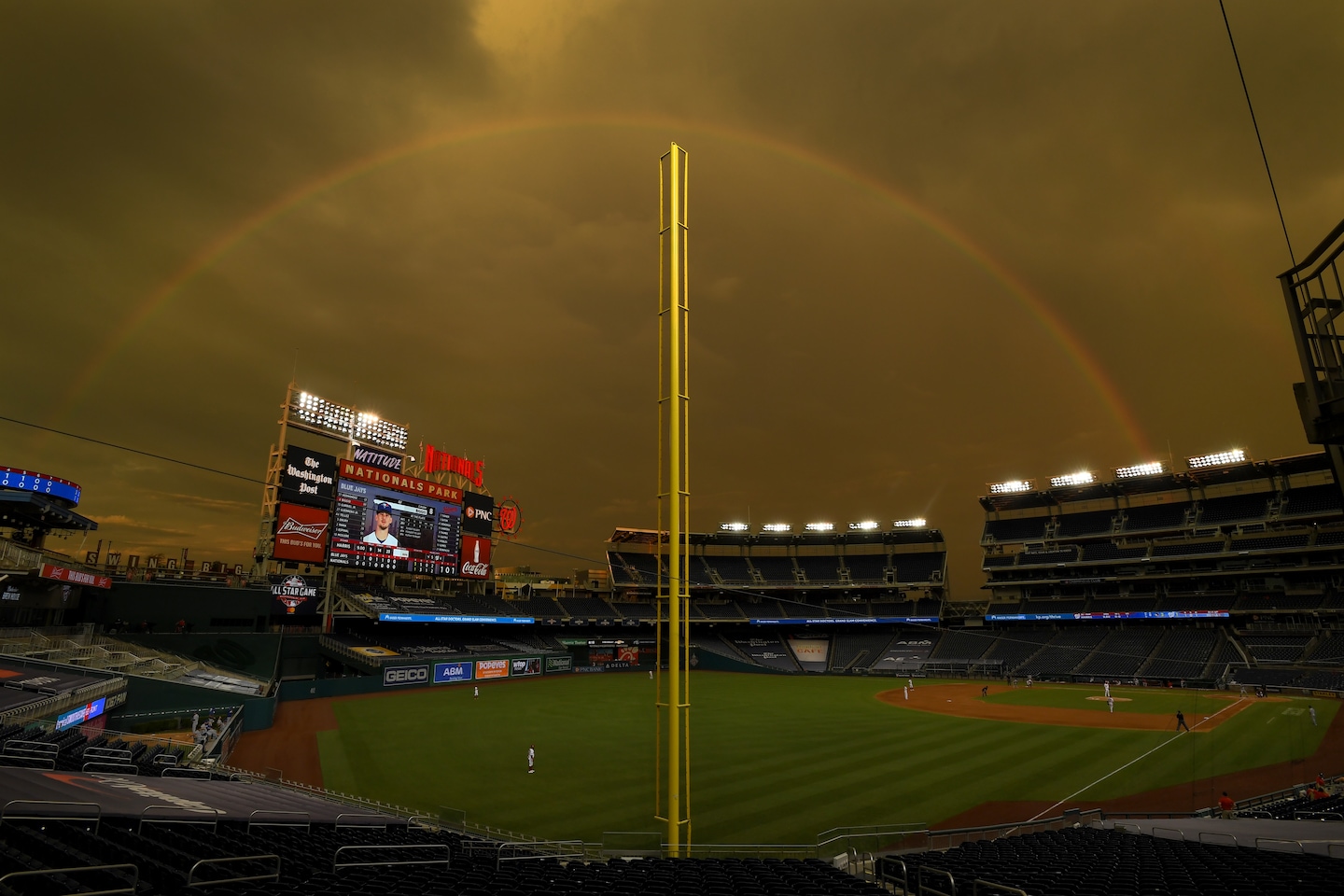

This is our life now. This is our game. This is the way it has to be, in the heart of summer, in the teeth of a global novel coronavirus pandemic that, at least on these shores, has no end in sight. For there to be sports — baseball, hockey, basketball, soccer, and soon, it seems, football — there must be sports without fans.

And most of the lucky few who are still let inside the stadium, to one degree or another, are faking it: You’re either putting on a TV show, or fabricating an in-game atmosphere out of thin air, or manufacturing the adrenaline that, without a crowd providing the fuel, no longer comes naturally.

“You have to keep in your mind: it’s not a practice game,” said Eric Thames, the Washington Nationals’ first baseman. “It counts. People are watching [on television] all over the world. [But] in terms of energy, it’s definitely not good.”

A good many people have expended a good amount of time, money and creative capital on making baseball sound like baseball, whether for the benefit of the players on the field or the viewers and listeners on TV and radio. And yet, it’s hard to find anyone who is fooled by the fake crowd noise or the familiar musical prompts that teams have kept as part of their game day soundtrack.

And it’s hard to find anyone involved in the production who thinks they are fooling anyone.

“The guiding principal is to make everything seem as normal as possible,” said Josh Kantor, the organist at Boston’s Fenway Park. “But what’s interesting about that is, there’s some illusion and artifice involved. [The fake crowd noise] is an artificial thing that’s being done to create the illusion of normalcy. And that’s true in my case, as well.”

Consider the crack of the bat — the sharp retort of a cylindrical piece of turned ash striking a cork-centered, yarn-wound, cowhide-covered baseball at 100 mph or thereabouts. As the signature sound of baseball, it is objectively superior to that of other major team sports, whether the squeak of sneakers on hardwood in basketball, the grating scrape of braking skates on ice in hockey or the controlled car wreck that is every play in football.

But the crack of the bat, beautiful and powerful, is meant to rise from the din of a crowd leaning forward in anticipation, much as Luciano Pavarotti’s tenor is meant to soar above an orchestra. That voice, naked and unaccompanied, is uncommonly powerful as a solo instrument — just as the crack of the bat in an empty stadium, without tens of thousands of human bodies to absorb the waves, sounds like a shotgun blast.

But throw a canned soundtrack beneath it, and it’s nothing but karaoke.

And that’s the sound of the national pastime in 2020: Baseball karaoke.

‘One fan in the ballpark’

Inside the stadium, the sense that baseball in 2020 sounds pretty much like baseball in any other year lasts until roughly the end of the national anthem. The music ends, silence ensues and the void is suddenly filled by a banshee wail from five stories above: F.P. Santangelo screaming, “Let’s gooooooooooo!”

“There has to be one fan in the ballpark,” explains the Nationals’ affable television color commentator, who screams those two words at the top of his lungs at every home game. “I’ve even stood and clapped on the air. Everyone knows I’m a homer. I’m going to keep cheering.”

Baseball in 2020 is full of those aural incongruities: noises that are suddenly way too loud, others that appear out of nowhere, voices overheard that are not necessarily meant to be heard.

Many of them are charming when you come across them on a screen, the sounds picked up by field microphones: Atlanta Braves outfielder Ronald Acuña Jr. singing absent-mindedly in Spanish. Washington Nationals pitcher Max Scherzer grunting with every pitch. Houston Astros pitcher Zack Greinke, from the mound, reminding his catcher, behind the plate, which signs they are presently using (“Second sign after two.”)

You never knew the bat could produce so many different sounds: the thud of a weighted doughnut being ejected from its barrel in the on-deck circle, the gentle tap on home plate, the angry bang of its return to the bat rack after a strikeout.

The distant “pop!” of fastballs meeting catcher’s mitts alerts you to the relievers warming in the bullpen, even before you notice them with your eyes.

But many of the ballpark sounds, escaping above the fake noise and into ears they were never intended to reach, are pure trouble. When you can hear almost everything that is said, danger is part of the bargain.

The Chicago Cubs and Milwaukee Brewers nearly brawled this season over chatter that wasn’t meant to leave each dugout. Nationals pitcher Stephen Strasburg, social distancing in the stands one day at the New York Mets’ Citi Field, was ejected from his seat some 15 rows up by a sensitive home plate umpire.

And the list of potty-mouthed ballplayers, caught by field mics uttering obscenities that typically get drowned out by crowd noise, is long and luminous: Joc Pederson and Max Muncy of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Jeff McNeil of the Mets, Josh Reddick of the Astros.

“He was a little disconsolate,” legendary San Francisco Giants play-by-play man Jon Miller intoned matter-of-factly after Muncy’s expletive made its way on the air.

In one epic rant this month, New York Yankees third base coach Phil Nevin dropped eight expletives in 10 seconds on umpire Angel Hernandez, who ejected him. New Yorkers may be used to such language, but other teams have instituted delays on their radio and television broadcasts, with a “dump” button to prevent such words from reaching fans.

In person, however, you may discover other wonders that had been hidden from you all these years by the ever-present blanket of real crowd noise. Such as: the fact that Nationals first base coach Bob Henley is a world-class hand-clapper: Clap. Clap-clap-clap. Clap-clap. Open hand on closed fist: thump. Then the other hand on the other closed fist: thump. And a spasm of hearty hand claps when the Nationals hit a home run.

He claps constantly — except when the sound system asks him to.

Sound system: “Eve-ry-bo-dy clap your hands! Clap-clap-clap-clap-clap-clap …!”

Henley: [Silence.]

‘Trying to create an audience’

Jerome Hruska’s job — well, one of them — is to inhabit the consciences of 30,000 invisible Nationals fans. It is, admittedly, a big ask.

The longtime public-address announcer at Nationals Park, Hruska had his duties expanded this year to include running the fake crowd noise — generated by an MLB-issued iPad containing sounds taken from a video game.”

And Hruska, bless his heart, leans into the job with an earnestness that belies the act of deceitfulness he perpetrates with each press of the touch screen.

There are 72 unique sounds to choose from, including a “bed” of constant crowd-buzz that can be soft, medium or large — and which Hruska expects to boost from soft to medium later in the season, as crowds would typically grow bigger and more enthusiastic, and perhaps to large in the postseason, if the Nationals get there — and various reactions of both the happy and dissatisfied types (but no booing). It is up to Hruska to decide how to deploy them.

“It’s a work in progress,” he said. “Philosophically, you’re trying to make it sound natural. But you’re actually trying to create an audience [at the stadium], even as you’re serving another [on radio and TV]. We know they can still hear us at home.”

On TV and radio, the sounds are passable imitations of the real thing. But in person, it comes across as something akin to white noise — barely noticeable, but both soothing and strange.

“It’s like you have two of your senses that aren’t coinciding with one another,” Los Angeles Angels third baseman Anthony Rendon said. “It’s like you’re looking at a pizza, but you’re smelling a hamburger. You hear noise, but you know no one’s in the stands.”

It exists to serve the home team’s players — “We want them to feel as comfortable as possible,” Hruska said — but even cranked up to its highest intensity, the noise isn’t likely to inspire the hometown nine to greatness. Players have made note of a certain flatness to the atmosphere that is sometimes difficult to overcome.

“Man, it’s hard. I’m not going to lie about that,” Dodgers closer Kenley Jansen said. “It’s so much easier to [feel a] lift if your fans are cheering you or the other side is booing, and you come out there and shut it down. It’s so much easier to pitch when there were fans in the stands.”

Aside from intensity, what’s missing from the noise is any sense of nuance — the mixed reaction. Case in point: The starting pitcher is pulled from the game in the seventh inning, having been lights-out through the first six, but running into trouble in the seventh and being left in the game for perhaps one batter too many. A lead is lost. A reliever is jogging in from the bullpen.

Under normal circumstances, the crowd would be a mixed bag as the starter trudges off the mound. There would be a hearty ovation for the pitcher’s valiant effort, an undercurrent of boos directed at the manager, and one or two drunks screaming expletives at the umpire for squeezing the pitcher on a borderline, full-count pitch a couple of batters ago.

Instead, all you get is a modest reaction from Hruska’s iPad, a couple of ticks of extra decibels, the aural equivalent of: “Nice game. Whatever.”

Teams have largely kept their in-game audio/visual production the same in 2020, in the interest of comfort and familiarity. Hitters get their walk-up music. Relievers get their entrance songs. A couple of runners on base might prompt a bugle call and a canned response: “Charge!” Stadium anthems are still stadium anthems. If you can’t escape from John Fogerty’s “Centerfield” this year, it is safe to say you probably never will.

A ballpark organ, however, is timeless. In Boston, Kantor, through his plexiglass window atop Fenway Park, looks out over the empty stands and reaches into his deep well of experience in various fledgling bands and ensembles to find the will to play his heart out for a gig where nobody showed up.

“It’s constant. There’s no way to not be aware of the lack of fans,” he said. “I’m slightly more accustomed to the emptiness of the ballpark now than I was when the season started. But I don’t expect to be totally used to it at any point this season. We’re all hyper-aware of everything in our lives that’s not the way it used to be. I feel very, very aware.”

If Kantor is doing anything different this season, it’s keeping things more upbeat, more sunny, more sing-a-long-y. He’s been known to segue from Bruce Springsteen’s “Hungry Heart” to Carl Carlton’s “She’s a Bad Mama Jama,” or from Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” to Biz Markie’s “Just a Friend.”

“You can’t gauge what’s working or not working, because you’re not getting that immediate response,” he said. “Sometimes, especially between innings when we’re not on the air, I feel like I’m really playing for the grounds crew. I’m playing for the security staff, for my A/V department colleagues. What’s going to put a smile on their face at a time when it’s hard to find things to smile about?”

At game’s end, he shuts down the instrument and turns off the light.

In Washington, Hruska packs up his iPad.

The grounds crew attends to the field, their shadows long in the late-afternoon sun. Equipment staffers are gathering up the bats, helmets and Gatorade coolers from the dugout. But otherwise, the stadium is silent — the good silence, the kind that belongs.

It is the sound of hope.