Middle America cannot be forgotten unless it first forgets itself

Twentieth-century American art and industry is unimaginable without the fertile ground of the Midwest, the Illinois of Ernest Hemingway and Gwendolyn Brooks, the Minnesota of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Bob Dylan and Prince, the Nebraska of Willa Cather and Johnny Carson, the Iowa of Grant Wood and John Wayne, the Colorado of Damon Runyon and Harold Ross, the Michigan of Henry Ford and Aretha Franklin, the Oklahoma of Will Rogers and Woody Guthrie. This list is just a morsel to suggest the banquet, omitting much more than it includes.

On Aug. 29, 1920, a child was born in Kansas City to a woman named Addie Parker. This mid-continent boomtown stank of money, literally — its stockyards in the Missouri River bottoms were among the busiest on earth. The Ford Motor Co. plant — the first outside Detroit — cranked out Model Ts for a car-crazy country. Prohibition was just a rumor from some far-off land. A local cartoonist named Walt Disney was fiddling with an idea called animation. A war veteran and sometime farmer, Harry S. Truman, was running a menswear shop downtown.

Addie’s boy was called Charlie. He was musically inclined, and for that he was in exactly the right place at exactly the right time. When he was a toddler, one of the first commercial radio stations in the United States went on the air in Kansas City. In search of content, WDAF began broadcasting dance music from a local hotel. In those days of uncluttered airwaves, the house combo could be heard across the country. Named for its co-founders, the Coon-Sanders Orchestra was dubbed “the band that made radio famous.”

That marked Kansas City as a music mecca. But the real talent was found closer to Charlie’s own neighborhood, along the glittering Black broadway of Vine Street, in the dance halls where jazz could be heard nightly. Bandleaders such as Andy Kirk, Benny Moten and Oran “Hot Lips” Page developed a riffing style that swung hard and free, and after the dancing stopped, the drinking kept going to fuel jam sessions that went until dawn.

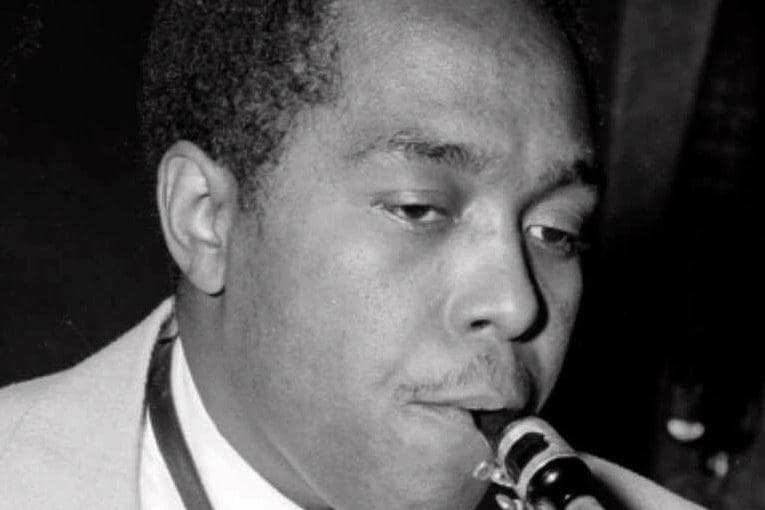

As a teenager, Charlie Parker began taking his alto saxophone to those jam sessions, where he met and played with some of the great pioneers. By then, pianist William “Count” Basie, a veteran of both Page’s Oklahoma City Blue Devils and the Benny Moten Orchestra, had formed his own band and hired Mississippi-born Lester Young to anchor his sax line on tenor. Kansas City was crawling with strong sax players, including the dean of tenor players, Coleman Hawkins (from St. Joseph, Mo.), and the lush and breathy Ben Webster (a local kid). But it was the former Blue Devils alto player Buster Smith, a natural teacher, who mentored Charlie Parker’s preternatural talent through those all-night jams.

You could say that Kansas City’s Charlie Parker didn’t become the Immortal Charlie Parker — the genius known as Bird — until he left for New York City as a young man. Featured in a band lead by Earl “Fatha” Hines, Parker dazzled his Harlem contemporaries with his lightning-fast fingerings and innovative chords, the building blocks of the jazz style that came to be known as “bebop.” Although Parker’s frequent collaborator, trumpet virtuoso John “Dizzy” Gillespie, would eventually insist that this was “the same basic music” jazz artists had been playing all along, bebop struck like a lightning bolt. Bird’s impact was seismic; he split the history of America’s music in two.

But New York needed Bird at least as much as Bird needed New York. By that I mean a vital cultural capital requires a constant infusion of new ideas, and those are found most readily from outside. Cut off from the world, sealed unto its smug self, a mecca of culture inevitably stultifies, perpetuating the status quo by rewarding those who court its approval.

Today, the country runs that risk. Our artists and intellectuals tend to live in a few places and to circulate among themselves. Their worldview is, like the famous New Yorker magazine cover, limited to New York or Boston or Hollywood or Silicon Valley, with the rest of America an empty unknown. To the extent that the rest of the United States accepts this forlorn identity and retreats into populist resentment, we reinforce the alienation.

A century after the birth of Charlie Parker is a good time for Middle America to rediscover its true nature: home to genius, incubator of audacity, wellspring of ideas. The heartland cannot be forgotten unless it first forgets itself.

Read more: