John Thompson bent the world to his vision. The world was better for it.

The small jammed gym was sweltering. But the 6-foot-10, 300-pound Thompson, pouring sweat, came prepared. He’d brought a huge bottle of soda, smuggled under his coat in a brown paper bag. Big John leaned back to take a big swig, then stopped suddenly and jammed the bottle and bag down between his legs and under the seats.

“This gym is full of big-time college coaches from all over the country,” said Thompson, as alarmed as if he’d just avoided a traffic accident. “If they see me, every one of them is going to tell everybody else that I was drinking out of a brown paper bag. And they won’t say it’s Pepsi.”

That’s one way I’ll remember Big John, who died at 78 Monday: aware of every competitive edge or weakness, funny, alert to the world’s manifold sins and wickedness, even as he relished every moment.

But there were almost as many Big Johns as there were days. Once, when I was a couple of years out of college, my mom mentioned she enjoyed the times she’d had late-night talks with that deep-voiced coach who’d returned my calls. They’d talked about child rearing and other subjects. Which coach? “John Thompson,” she said.

“Those farm girls are wise,” Thompson informed me, referring to my mother.

Those who refuse to bend to the world as they find it usually end up in one of two ways. The world breaks them. Or, far less often, they bend the world to them. John Thompson bent the world and made it a bit better.

To understand Thompson, it helps to go back a long, long way. One Saturday morning almost 50 years ago, John, his two young sons, John III and Ronnie, and I sat in the living room of Father Raymond Kemp, a priest and lifelong D.C. activist for social change.

John had just begun to coach Georgetown University, taking over a program that went 3-23 the year before he arrived. But he was not interested in discussing his own program, obscure at that time, or its long-shot prospects. He wanted to brainstorm, almost plot, you might say, with Kemp. Thompson wanted to know, at the granular level or as a leader, how he could help effect change.

At that time, Kemp was on the D.C. Board of Education; he later worked with the 14th and U Coalition and the D.C. Central Kitchen. I was reporting.

The talk at Kemp’s house that day was, painful to say, about many of the same issues of social injustice and systemic racism which are debated nationwide today.

How do you go from ideas, theory and good intentions to day-after-day impact on the lives of individuals and communities? How do you get Whites — Kemp spent 18 years as a White pastor at mostly Black parishes — to go beyond “not-being-racist,” to being part of solutions.

“Money,” Thompson would say. How do you get more of it to people who need it? How do you educate, and network, more successful Blacks so they continuously grow in economic influence? Thompson saw Black and White, but he’d say, “Don’t forget, the world is green.”

It is a basic misunderstanding to see Thompson first as a Hall of Fame basketball coach, though he loved his sport and, behind his tough-love facade, adored his teams. Before anything else, he saw himself, and truly was, a catalyst for change who used his national platform, to teach and “preach” social justice.

As a devout Catholic, he saw himself as just as flawed as the next fallen sinner, just as prone to pride or mistakes of judgment. A few times, winning battled with principle as the force which drove him. But I covered his whole career, as a beat writer or columnist, and I can count on my fingers the times that principle lost.

For 27 years as coach at Georgetown, “with his booming laugh and passionate opinions, Thompson was one of the most disagreeable people in this country. Agreement bored him. Debate invigorated him. Everything he disliked he discussed, with bouquets of exclamation points attached. In a sports arena awash in happy cliches, he left the easy compliments to others.

“A cheerful consensus on any issue — especially one that involved race, class, money, education or basketball — raised his suspicions. To quote P.G. Wodehouse, “If not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.”

“Thompson’s strength was not the freshness of his perspective or the depth of his insight, though he had both. What gave his positions power was his simple belief that college sports should live up to the code that the country claimed it lived by. Others asked. He demanded.

“What Thompson brought to his bully Hilltop pulpit was intense conviction and a street-wise, book-polished way of making his point with a sports anecdote that often hid a parable at its core. Even the deflated basketball in his office was a metaphor.”

A visit to that office in GU’s McDonough Gym was a graduate course in Big John. First, the door had no name. You thought it might be stairwell or storage closet. You’d nudge it open to peek inside. The first glimpse, in this place of dirty towels and socks, was a shock: an elegant, tastefully under-furnished room with Asian lamps, early American furniture, photo-murals of Washington vistas and faint sky-blue walls and rugs.

“You sure didn’t think it looked like a coach’s office,” one Washington NBA star who’d gone to Duke told me. “This looks like a beautiful Southern home.”

That door also had no bell, no buzzer. So, you had to push it open. Just as it was open wide enough to enter, a tiny noise began above your head — butterfly chimes, the gentlest of alarms. Because it came a beat later than you’d expect, it made you feel like an interloper as a gong never could.

“Every player notices it the first time,” Thompson told me. “They even put one above the door of the training room, so I couldn’t sneak up on them.”

The books on Thompson’s shelf were all chosen to make a point to players. And they showed the range of interests he expected of them — or at least hoped they’d find in themselves. “Power: How to Get It, How to Use It.” “Winning Through Intimidation.” “You Don’t Have to Be in Who’s Who to Know What’s What.” Machiavelli’s “The Prince.”

Under the desk motto “To Err Is Human. To Forgive Is Not My Policy,” you’d find “Your Mastery of English” and “Spell It Right” as well as “The New Etiquette.”

Then came the counterpoint: Harry Truman on how to make things work. Aesop’s Fables. James Thurber’s humor. “Quotations From Chairman Jesus.” “A Controversy of Poets.” “Ideas and Opinions of Albert Einstein.” A little volume of Zen paradox: “If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, Kill Him.”

Every one of those books had a common purpose: to help his players grow. The opposite side of that Thompson coin was that he believed his players needed time and space and less, rather than more, celebrity if they were going to do that growing. We debated his view that his players should be interviewed as little as possible and never as freshmen. I could never get around his central point about defending the privacy of his players from constant inspection.

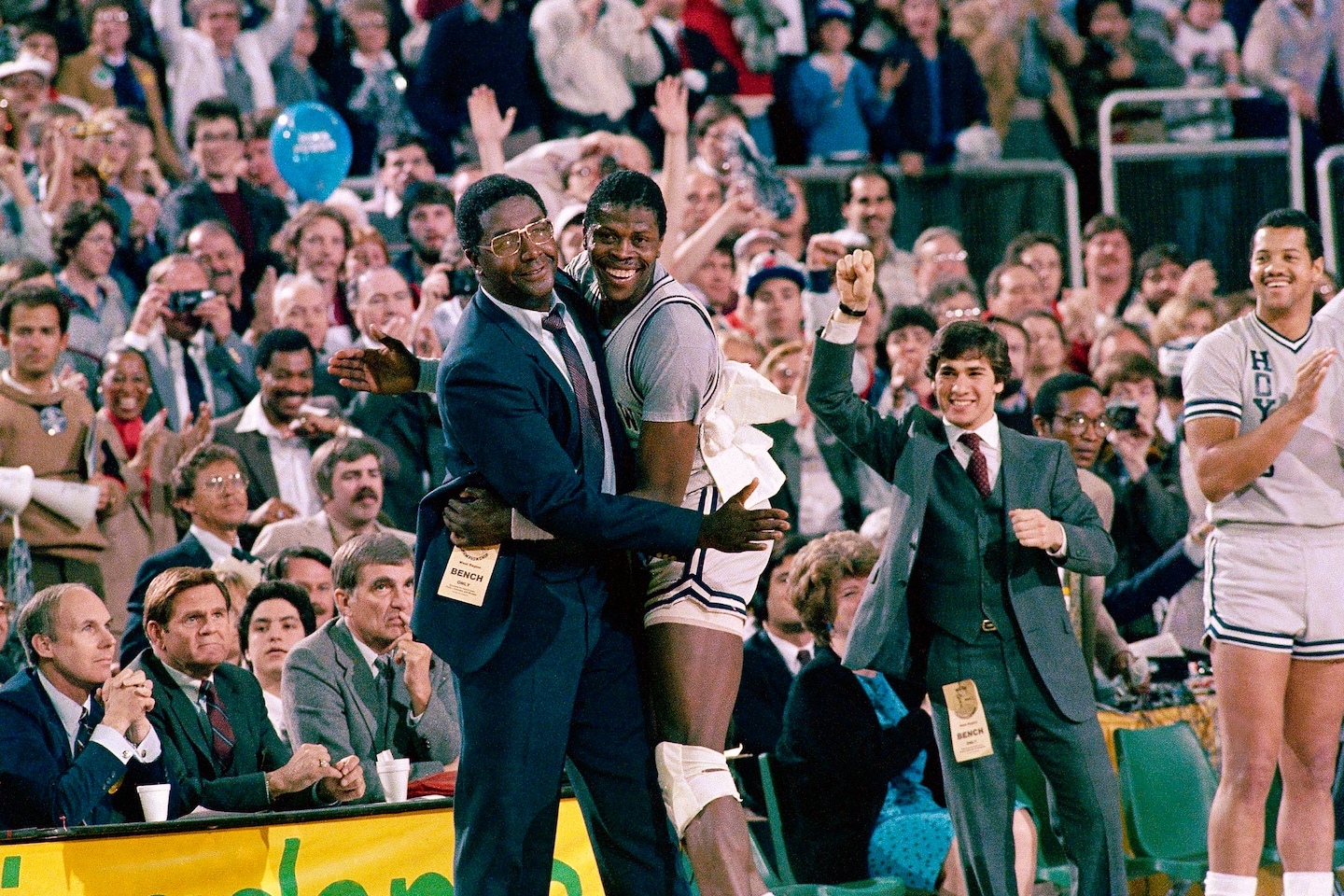

This week, as America continues debating serious issues — at times prompted by its athletes — a serious man will be mourned, a wise man who also happened to be a national championship basketball coach. Thompson once told me that the center he’d played behind on the Celtics — the great Bill Russell — was also one of his life mentors.

“You should live a life with as few negatives as possible,” said Russell, “without acquiescing.”

Thompson never did. In times of death and grief, as well as memories and praise, we often say of friends that we knew well, “He will be deeply missed.”

But with John Thompson’s passing, something truly will be lost.

From the archives: