Powerful House committee chairman faces liberal primary challenger in race that could reshape Congress

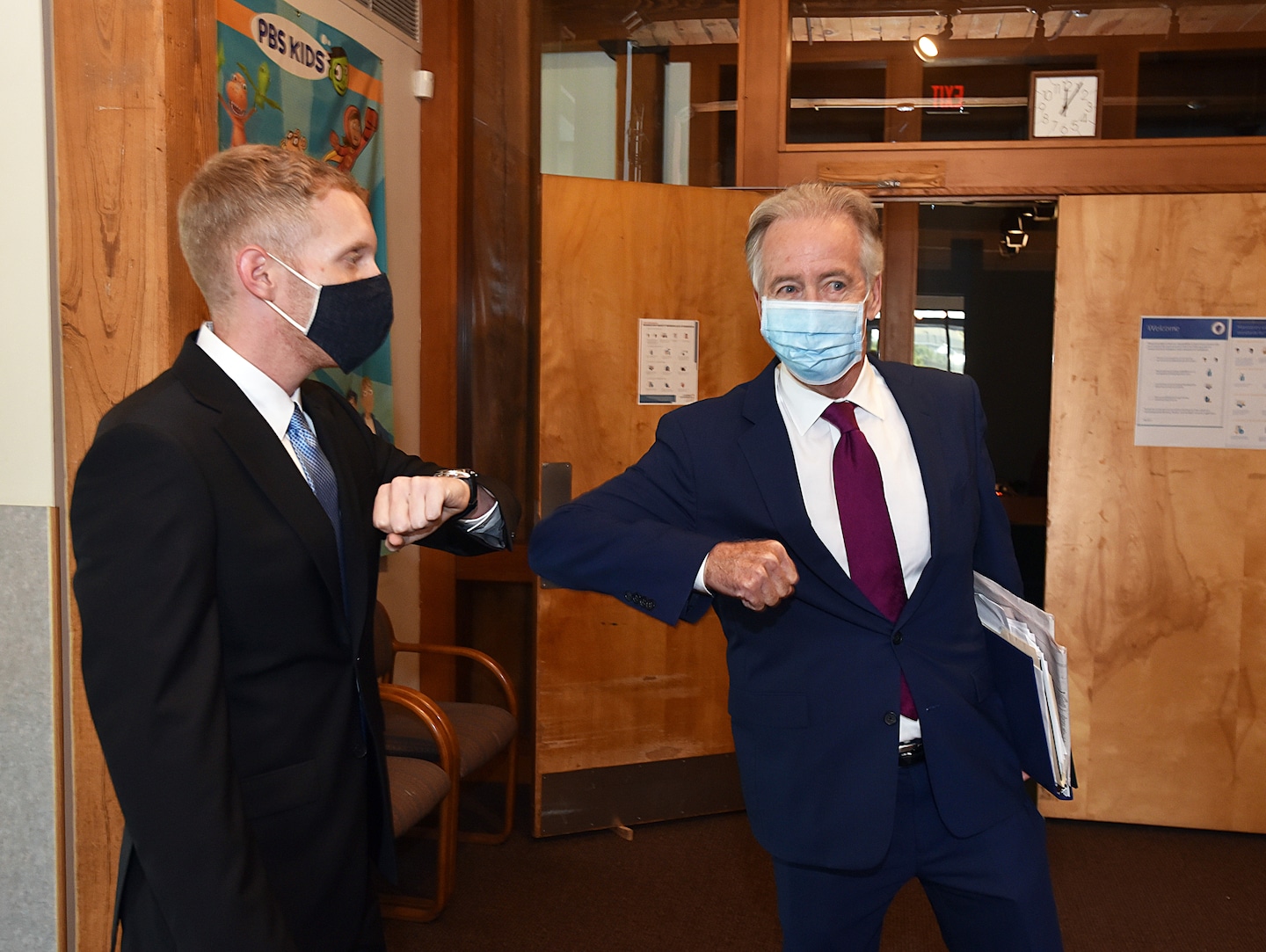

The contest between Neal, 71, and Morse, 31, stands as the most significant current clash between the establishment wing of the Democratic Party and the liberal opposition that is clawing to push the party to the left in the era of Trump. In the wake of stinging losses by other House Democratic leaders — including Foreign Affairs Chairman Eliot L. Engel’s loss to Jamaal Bowman in New York in July — Pelosi and Neal are hoping the Ways and Means leader will stem the tide, and demonstrate experience and moderation can triumph over liberal ideology at a moment of national division.

“Richie Neal is an absolute leader in the Congress, a progressive leader in the Congress,” Pelosi said Thursday at a news conference where she mounted a full-throated defense of her longtime ally. “People will say what they will say, but I know what he has done, and it would be a tremendous loss to that district to lose the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee.”

Morse and his supporters are painting Neal as a symbol of all that is wrong with establishment Democrats. They accuse him of not moving fast enough to seek President Trump’s tax returns after Democrats retook the House majority in 2018 and Neal assumed control of the Ways and Means Committee. And they assert he has blocked bold legislation, such as Medicare-for-all, in favor of incremental change.

Neal disputes such criticisms, highlighting his accomplishments for the district, insisting he did all he could to responsibly pursue Trump’s taxes — an issue that is tied up in court — and alleging that many of Morse’s stances are unrealistic and downright irresponsible.

“I’ve delivered,” Neal said repeatedly during a recent debate, ticking off numerous projects in the district he has worked to support, as well as his role authoring the $2 trillion Cares Act from March — which Morse says he would have opposed because it didn’t go far enough.

A loss by Neal in the closely fought race would send shock waves through Capitol Hill, putting every longtime incumbent on notice that none of them is safe. Replacing a consensus-building moderate with a liberal newcomer would also tilt the Democratic caucus further to the left, further polarizing an already gridlocked Congress. Many pieces of legislation central to the Democrats’ strategies, such as tax and health policy, must go through Neal’s committee, giving him enormous control over the party’s agenda.

The winner of Tuesday’s primary is guaranteed a seat in Congress, as no Republican is running in the Democratic-leaning district.

“Almost every major piece of legislation has to go through the Ways and Means Committee,” Morse said in a recent interview in Williamstown, a college town at the upper edge of the sprawling 1st Congressional District, which stretches from the rural western reaches of the state to take in Springfield, where Neal served as mayor in the 1980s. “The chairman has a lot of power. But he dropped the ball. He didn’t use that power to hold this president accountable. He is using it to block Medicare-for-all, a Green New Deal and wealth tax. I think people realize what’s at stake.”

In the recent debate, Neal described the Green New Deal as “a worthwhile goal” but insisted only legislation that actually passes “changes our lives.”

“What is it, holding a news conference that changes our lives? Going to a demonstration that changes our lives?” Neal said. “You can shape the narrative, but it’s still legislation that makes the change.”

Morse entered the race 13 months ago and was endorsed by the Justice Democrats not long after. For Justice Democrats, Morse’s experience as a long-serving and well-known mayor, with a compelling family story, made him an attractive candidate.

“This was always our toughest race, because as Ways and Means chair, Neal has the biggest war chest of any incumbent we’ve challenged,” Justice Democrats spokesman Waleed Shahid said. “He uses his power to frighten anyone who might defy him. He’s the epitome of a corporate Democrat.”

The incumbent outspent Morse, though the challenger was able to get on the air and stay there. According to Federal Election Commission reports filed in the middle of August, Morse had raised $1.3 million, spending most of it; Neal had raised $3.7 million and spent even more than that, drawing on funds not used in the 2018 campaign. On Sunday, the Morse campaign reported they had hit $2 million in fundraising.

Neal, unlike some of the left’s targets since 2017, was also ready for a primary. In 2018, he faced his first Democratic opponent in years, an attorney named Tahirah Amatul-Wadud. She accused Neal of being indebted to his donors. She raised less than $150,000 but won 30 percent of the vote, while Neal built a campaign operation he says prepared him for the Morse race. Public polling has found Neal leading Morse, though both camps are unsure of how early voting, mail voting and interest in the state’s U.S. Senate primary — which pits Rep. Joe Kennedy against incumbent Sen. Edward J. Markey — will affect turnout.

“You never want to get caught sleeping,” Neal said in an interview. “I take this very seriously. I’m pretty visible. Obviously, you have to be in the district, but you also have obligations in Washington. You have to combine politics, visibility and a pretty keen mind for achievement.”

Weeks ago, and for the first time, the race made national news — and not for reasons either candidate wanted. According to Morse, his campaign had been hearing for months that a damaging story about him was “being shopped around.” On Aug. 7, the College Democrats of Massachusetts announced Morse was disinvited from future events because he had “made college students uncomfortable” in his role as a guest lecturer at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

The letter did not accuse Morse, who is unmarried and gay, of any specific violation, and the candidate put out a statement declaring “every relationship I’ve had has been consensual.” He met with staff, who unanimously urged him to stay in the race, even as some of his endorsers reevaluated their support.

Under scrutiny, the allegations fell apart. Reporters for the Intercept discovered some members of the College Democrats had plotted to accuse Morse, based only on friendly direct messages he’d sent to students, with the hope of securing favor with Neal. Morse’s endorsers returned, and he saw the strongest fundraising of his campaign, as Neal denounced the plotters.

“I’ve made it clear that any suggestion that my campaign or that I was involved in this is not consistent with character and career,” Neal said, repeating his call for a thorough investigation. In Morse’s view, the accusation backfired completely.

“There was a guy in a parking lot, when I was walking into a grocery store where we were handing out literature, and he was like: ‘You got my vote after I saw what they tried to do to you,’ ” Morse said. “At the farmers market, people were saying: ‘That was disgusting, what they tried to pull on you.’ ”

On Saturday, the new leadership of the state’s College Democrats apologized to Morse, writing they were “deeply sorry for the distress that the public reaction to the letter must have caused you.”

But Morse’s campaign and allies had already refocused on the original themes of the campaign: donors and what Neal would or would not let out of his committee. Justice Democrats had sent six staffers to organize for Morse while its PAC had spent $500,000 on ads. Fight Corporate Monopolies, a PAC formed this year to help liberal challengers, had already run commercials accusing Neal of selling out patients because of his corporate donations.

Neal, who has benefited from six-figure ad buys from PACs such as Working Americans and Democratic Majority for Israel, said the attacks over medical billing legislation were simply ignorant.

“I wish every reporter would go back and take a look at who was on the other side of this issue,” he said. “I support the patient, the hospitals, the doctors and the consumers. The insurance industry’s on the other side of this, and I feel quite confident to say I don’t think Alex Morse knew who was on the other side of this issue.”

On Aug. 22, as early voting got underway in the 1st Congressional District, Morse gathered some supporters in a socially distanced circle and thanked them for their work. He was driving from town to town in the most rural part of the state. Neal had headed to Washington for a vote on the Democrats’ bill to boost funding for the U.S. Postal Service, but what, asked Morse, did he really do for the district?

“When he does come to the Berkshires, he’s meeting with corporate CEOs or hospital executives,” Morse said. “It’s important that people here have a member of Congress that you can trust is for regular people here in the district.”

A persistent dispute throughout the campaign — and among House Democrats on Capitol Hill since they won back the majority in the 2018 midterms — has been Neal’s approach to trying to obtain Trump’s tax returns. The president broke long-standing precedent by refusing to release the documents voluntarily. As Ways and Means chairman, Neal — along with his Senate counterpart — has the power under the law to demand the tax returns of any individual. He came under immediate pressure from liberals in the Democratic Caucus and outside groups to take that step.

But Neal delayed, which critics attributed to a reluctance to alienate Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and other officials within the administration, with whom Neal was trying to strike deals on infrastructure and trade. Privately, there was much grousing among the more liberal members of the House Democratic Caucus that Neal moved too slowly, criticism Morse has echoed publicly in the campaign.

“He would rather work with them than hold them accountable,” Morse charged at one recent debate, referring to Neal and Trump administration officials. Morse said he was “incredibly disappointed in the lack of urgency.”

Neal insisted he had proceeded deliberately to assemble the best case possible to obtain Trump’s returns, one that would stand up to scrutiny and likely to set precedent.

“This is a case that is going to reverberate throughout American history. I am not going to screw this case up,” Neal said, adding that Pelosi had supported his approach.

“You don’t work for the speaker,” Morse retorted.

Neal finally formally asked the IRS for Trump’s tax returns in April 2019, four months after becoming chairman. After Mnuchin refused to hand them over, the Ways and Means committee issued a subpoena for the documents. Democrats filed a lawsuit against the administration in July of last year after Mnuchin made clear he would ignore the subpoena.

Neal’s lawsuit is not expected to be resolved until well after the election, and the odds of Trump’s returns becoming public in time for the election have dramatically dwindled. Pelosi has said Neal would continue to seek Trump’s tax returns next year, even if the president is defeated in November. But Neal will face his electoral reckoning Tuesday, much sooner than Trump.

Werner and Stein reported from Washington.