Millennials are the poster children for government fiscal failure

In other words, if the business cycle is already self-correcting, what’s the hurry? In fact, what’s the need, given the price tag for proposed fiscal relief?

For one, this supposedly “strong, V-shaped recovery” shows worrying signs of stalling. New jobless claims rose last week; small-business activity has flatlined; millions have depleted their savings or fallen into poverty as federal aid has dried up. Massive state and local government layoffs, forestalled while officials held out hope for federal help, are likely to come soon. They will make things much worse.

Even if you ignore these warnings and assume that growth will continue apace, that pace isn’t one Americans should settle for. The government’s duty is to help the economy recover as fully as possible as quickly as possible. This is both to allay serious pain today and reduce scarring that could persist tomorrow.

We’ve already seen what happens when officials reject aggressive fiscal interventions when they’re needed, or pivot prematurely to austerity. They did just that after the last recession. For living proof of the damage that comes from such stinginess, just look to the sorry state of my own generation.

We millennials have been unusually unlucky. We’ve experienced two once-in-a-lifetime recessions within the first decade of our careers, and we still haven’t recovered from the first one.

Even before anyone knew the enduring consequences of the Great Recession, economists had ample evidence that graduating into a bad job market has long-term (perhaps lifetime) scarring effects on income and other measures of well-being. Recent research suggests such damage can even be fatal: Cohorts that graduated into the harsh labor markets of the early 1980s had higher mortality rates in middle age than did counterparts who graduated into better economies.

Another recent paper looked specifically at the Great Recession, the subsequent anemic recovery and the “Lost Generation” that resulted. This study, by University of California at Berkeley professor Jesse Rothstein, found that young college graduates who started their careers under exceptionally bad economic conditions had a permanently lower likelihood of employment later on. Those who ultimately did find work got stuck in lower-paying career tracks for years.

Other studies, including from the Census Bureau and the Federal Reserve Bank , have likewise found that millennials ”are less well off than members of earlier generations when they were young, with lower earnings, fewer assets, and less wealth.”

These scars are part of the reason why, even before the pandemic and accompanying recession, younger adults were already behind on major life milestones.

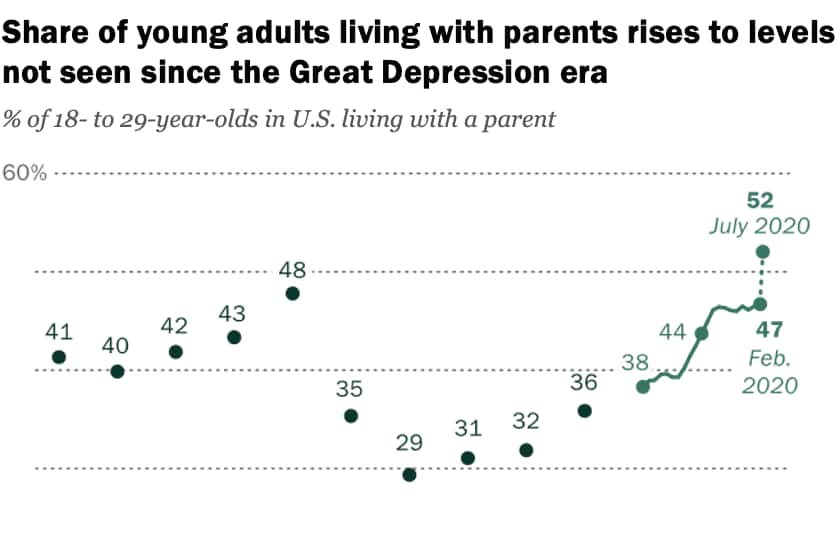

Millennials are less likely to be married than earlier generations were at the same age, or to have children. And, the stereotypes of basement-dwelling are true: We’re more likely to still live with our parents.

There was a surge in young adults moving back home during and immediately after the Great Recession. The trend was expected to reverse eventually but never did. Since the pandemic began, it has supercharged: For the first time since at least the Great Depression, most young adults now live with their parents, according to the Pew Research Center.

To be sure, some young adults are bunking with Mom and Dad because they wanted to escape dense cities during a lockdown, or because their dorms closed. But many returned to the nest — or never left in the first place — because they lack the financial footing to rent (let alone buy) their own homes.

“In this place in my life, I wanted to live on my own,“ says Eric Rivera, a laid-off public relations worker who turned 30 while sheltering in place with his parents. “I wanted to have really nice furniture that’s not from Ikea. I wanted to have kind of a senior role in my career. That kind of was just turned upside down.”

Millennials’ collective failure to launch is not due to any alleged predilection for avocado toast or other frivolities. It’s the result of a sharp economic contraction, followed by the federal government’s decision to withdraw fiscal support (including to states and cities) too soon, which let poor hiring conditions fester for far longer than necessary.

In the years after the financial crisis, successive classes of unlucky students kept graduating into a stagnant job market. The same phenomenon threatens to repeat because, once again, Congress refuses to act aggressively on fiscal aid, and the young are residual claimants on such government failures. The Class of 2020, just like the Classes of 2008 to 2012 or so, has already fallen victim to a severe recession. Congress must do whatever it takes to prevent the Classes of 2021 — and onward — from suffering the same fate.

Read more: