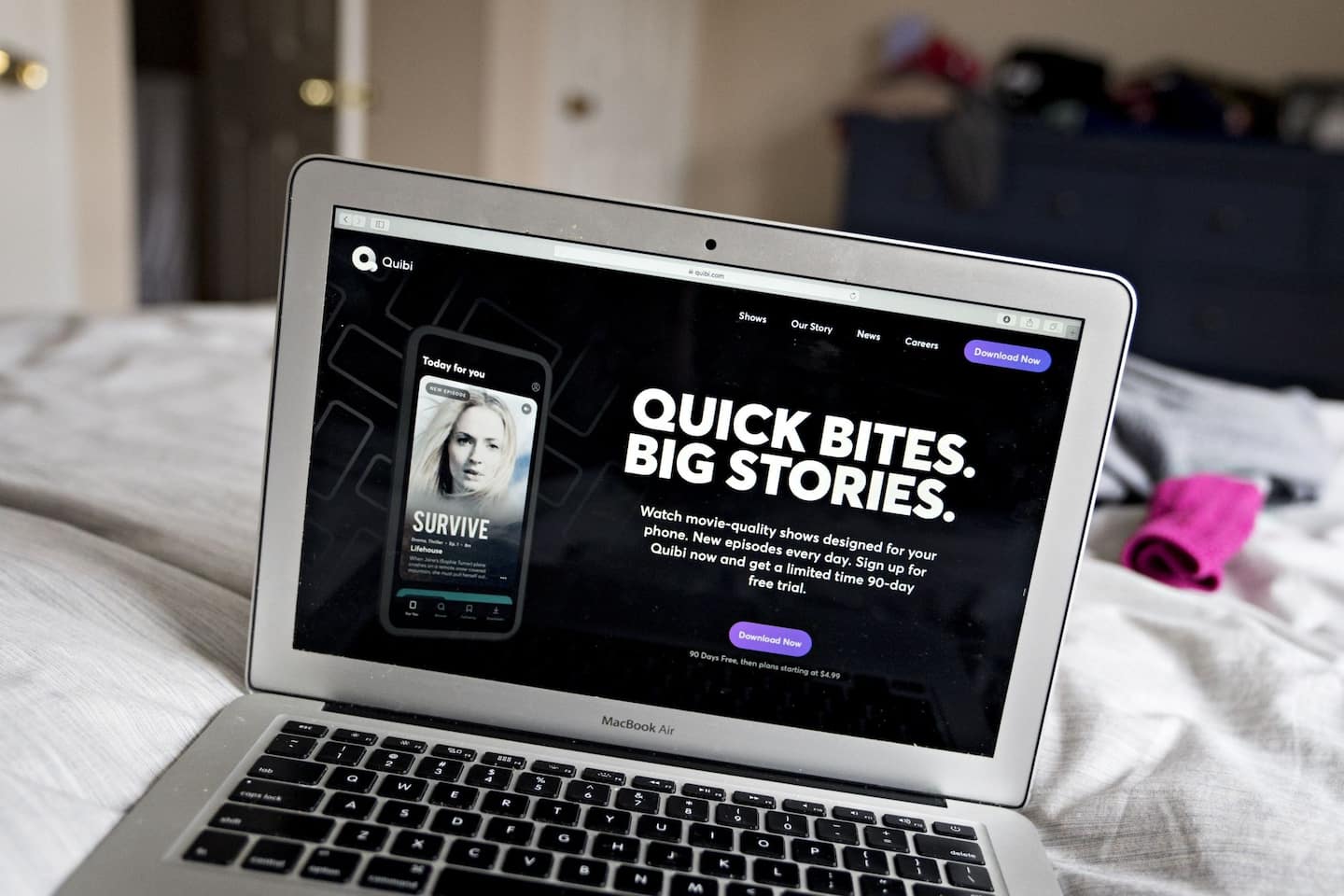

Quibi to shut down, abruptly ending a once-audacious play

Among the causes were a crowded marketplace and coronavirus lockdowns that made mobile less necessary, along with reviews that declared some of its content scattered and its marketing scattershot.

In an open letter distributed to reporters Wednesday, founder Jeffrey Katzenberg and chief executive Meg Whitman — two legends in their respective fields, movies and technology — described the dashed hopes.

“Our failure was not for lack of trying; we’ve considered and exhausted every option available to us,” they wrote. The pair reportedly had been shopping the service.

“We have reluctantly come to the difficult decision to wind down the business, return cash to our shareholders and say goodbye to our colleagues with grace,” they added. It is not known how much the company has left in the bank.

The shutdown, they said, was “likely for one of two reasons: because the idea itself wasn’t strong enough to justify a stand-alone streaming service or because of our timing.”

Born of Katzenberg’s ambitions to carve a new path after he sold DreamWorks Animation to Comcast in 2016, Quibi began attracting notice after receiving a torrent of cash from investors that included every major Hollywood studio. The attention kept coming after he hired Whitman, a former leader of eBay and Hewlett-Packard.

Katzenberg’s goal was try to rejuvenate an old form much the way he did for animation at Disney and then at DreamWorks Animation. Short-form content had thrived as mass entertainment in the days of newsreels and movie-screen serials, and Katzenberg bet it could be newly popular — and profitable — in the days of mobile.

At its low-slung, glass-heavy headquarters not far from the landmark Hollywood and Highland intersection, Katzenberg and his team of hundreds sought to sign up and curate this material, which would be available for a $5-$7 monthly smorgasbord fee. By doing so, Katzenberg was making a bold bet against bingeing. He told The Washington Post in an interview that “in-between moments” dominated modern life and could be filled with polished content. Rather than just lean back for eight hours of “Stranger Things,” he believed Americans on the run wanted to devour eight minutes of quicker things.

A pricey Super Bowl ad in February epitomized the scale of the ambition.

In April, Quibi went ahead with its launch despite an emerging recession that would squeeze both its advertisers and customers and despite encountering the more obvious hurdle that a company designed to serve entertainment on the go wasn’t built for a time when people were staying home.

Katzenberg remained bullish anyway. “We spent a year and a half working with the best storytellers and creators in Hollywood, and then making content beautiful on phones in a way that I think is not like anything you’ve ever seen before. I think people will appreciate that,” he said in the April interview.

The programming strategy he’d unveil ranged from high to low, a reboot of “Punk’d” mixed with a rejiggered “60 Minutes,” a reality show with Chrissy Teigen accompanied by a slick new version of “The Fugitive” with Kiefer Sutherland. Top-tier creators such as Antoine Fuqua and Katzenberg’s former DreamWorks partner Steven Spielberg were recruited.

Yet for all the range, the service soon struggled to find its niche and had few breakout hits.

The brand’s technology, meanwhile, did not achieve the kind of grass-roots appeal or democratic utility that tends to make apps popular, as it has for the decidedly non-Hollywood TikTok. People may want to watch videos on the go, it turned out, but mainly the ones they and their friends supplied themselves.

Josh Constine, an executive at the capital fund SignalFire, said that Quibi missed an opportunity by not optimizing its content for the platform.

“Despite being built for a touch-screen interface, there’s little Bandersnatch-style interactive content so far, nor are the creators doing anything special with the six- to 10-minute format,” he wrote.

Quibi also might have missed a fundamental truth: people don’t like watching addictive stories on their phones because they’d rather keep those phones free to tweet, text and Instagram about them. The second screen, in other words, requires a first.

The numbers bore this out. According to data firm Sensor Tower, the Quibi app has been installed just 9.6 million times since launch, a modest number further besmirched by the fact that many users were not paying; Quibi decided to offer its service free for three months at launch, hoping consumers would stick around and open their wallets later.

Running beneath Wednesday’s news was a story of old and new guards. As many traditional entertainment firms lurch fitfully toward Silicon Valley, Quibi was the most aggressive in seeking that combination from the start.

There may be other such unions that succeed. And highly produced mobile content may yet have its moment. But on Wednesday the most prominent attempt to sell those stories had flopped, and one of Hollywood’s most storied executives had failed with it.