My mother has never taken her right to vote for granted, and I can’t either

As Black children in 1940s America, they were taunted with stereotypes and hateful names. On several occasions their educations were interrupted, or completely halted, because they had to work. There were real railroad tracks that separated the Black part of town from the White part; in the air hovered the constant threat of random acts of racial violence. And many in my mother’s community, including her mother and father, were routinely blocked from voting simply because they were Black.

I think about these stories in this so very surreal year of 2020, as we near what well might be the most important presidential election in generations. I am not one of those folks who believe that voting is the prescription for everything, the singular step that will magically transform America or even my own life. No. But I do believe what my mother taught me.

The moment I turned 18 — at the height of the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s — my mother said to me that I had to register to vote, and I had to vote always. She was adamant that I not take for granted that basic right.

Given that she, a single mother, had had to deal with poverty, welfare, food stamps, government cheese and run-down tenement buildings filled with rats and roaches, my young mind could not at first understand why voting, in particular, mattered to her so much.

But as the years passed, and the stories continued to be remixed by her, I got some clues. She had turned 20 years old on Aug. 28, 1963, the very day of the historic March on Washington where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. My mother would tell me that she knew “something big” was happening that day in Washington, something that could help citizens like her. She was not sure just what it was, especially since she was too poor to afford a television or a radio at that time.

But she came to understand, as she bounced from one low-skilled minimum-wage job to the next in New Jersey — where she and two of her sisters had migrated — that if she wanted a better life for herself and for me, her only child, that she had to be aware of and engage in local politics and in the politics of her union. She had to use her voice — and one of the most important ways to do that was to vote.

So vote I did. And once I landed at Rutgers University, I not only got involved with supporting the presidential campaigns of Jesse Jackson, but also worked with fellow student leaders and civil rights veterans in Alabama and other places to resist the voter suppression so rampant in the 1980s.

Never did I, or my mother, imagine back then that I would spend my entire adult life, in some form or fashion, working around voter education, encouraging voter registration and protecting the right to vote.

Never did she imagine a Black president could be elected in her lifetime — which is why a framed picture of Barack and Michelle Obama and their two daughters is hanging on the wall of her senior-living apartment, as if they were family. Never did she imagine her child running for Congress, as I did.

Nor, however, could my mother have fathomed a global pandemic that disproportionately affects Black people and other people of color. Nor could she have foreseen that today, in 2020, voter suppression would remain a jarring reality for millions of Americans.

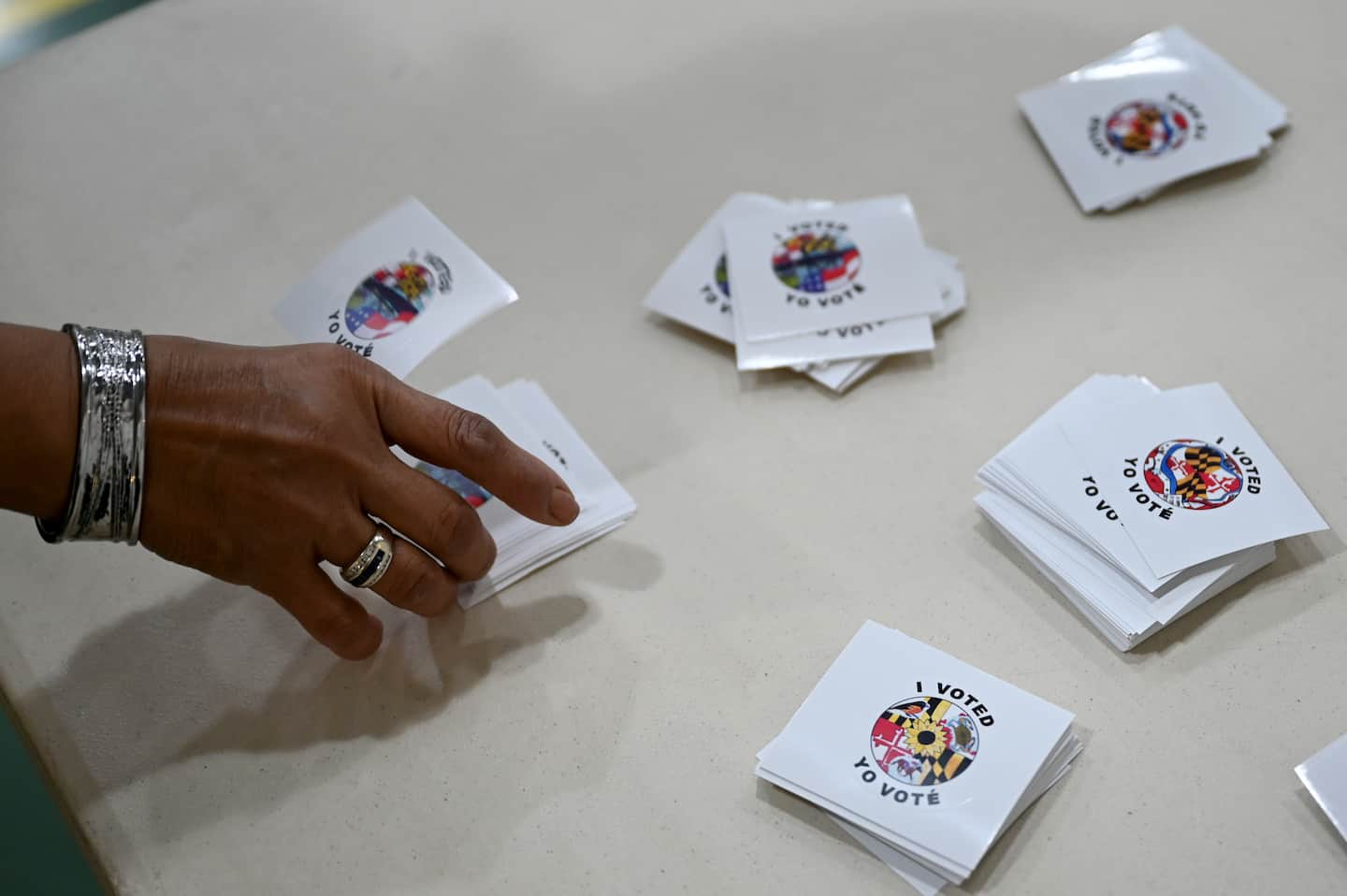

This is why my mother has already voted — voted early, something she had never done before. She has not come this far to risk being turned back now.

I do not know what is going to happen on Election Day, or in the days and weeks after. What I do know is when I vote on Nov. 3 — as soon as the polls open, hoping to avoid both the long lines and covid-19 — I will be doing so not only for myself, but also for my mother, and for all the mothers who have come and gone — waiting, praying, pushing hard, for a better and more just day.

Read more: