The ultimate survival guide to election night and beyond, in 17 questions and answers

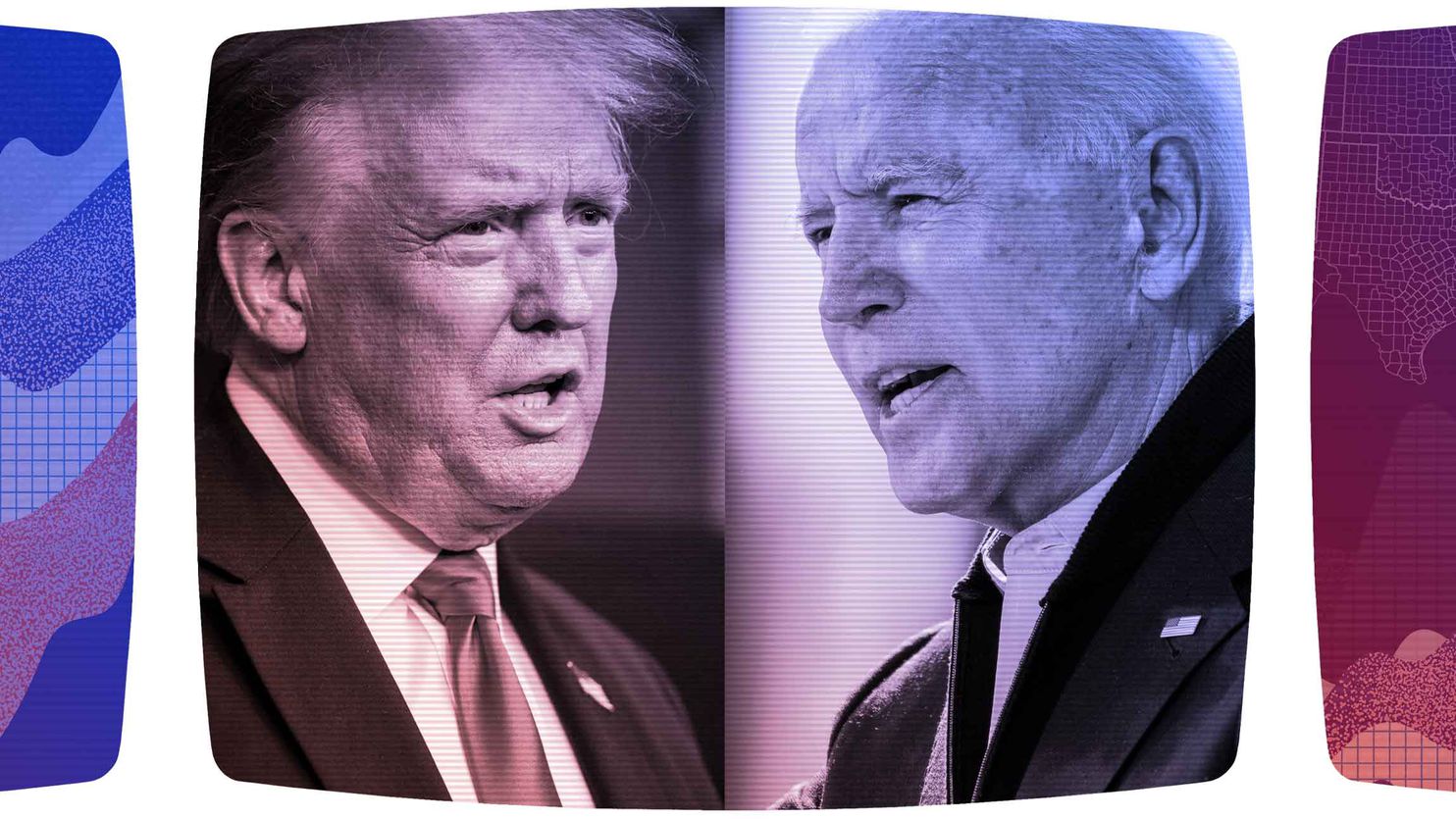

For many of us, the contest between President Trump and former vice president Joe Biden is the highest-stakes presidential election we have ever lived through. And given the conditions under which this election is taking place, it may well take time for states to carefully count ballots and certify election results, as well as to resolve legal questions related to the voting process. That doesn’t mean something has broken down in the electoral process. Getting the results of this election right is more important than getting them fast.

But if waiting is driving you crazy, you’re not alone. This guide will walk you through what we do know about how the election is going to proceed; what to watch out for as Election Day approaches; and what to look for on election night, and perhaps beyond, as news outlets try to process the results — and the candidates and their surrogates try to spin them.

We’ll be updating this guide regularly with the latest poll numbers. If you have more questions about the 2020 election, our colleagues in the newsroom are taking reader queries.

1

What’s the best way to measure which candidate is ahead? Who is really leading?

Polls, despite everything. State-level polls, to be precise. And Biden, by a greater margin than Hillary Clinton four years ago.

True, polls aren’t perfect. National polls did a great job of predicting the 2016 popular vote. But some battleground-state polls underestimated Trump’s strength and missed a late swing in his direction, with the result that they didn’t predict his electoral college win. That could happen again.

So far, though, Biden’s lead in the polls has been large and stable. He’s ahead by nine percentage points in national polls — a margin that, if it holds up, will probably prevent Trump from pulling off a win in the swing states. Major quantitative forecasts — which are a tool for analyzing polls, how they change over time and the results they suggest are most likely — also give Trump between a four and 12 percent chance of winning.

That’s not a guarantee of victory, but Biden is in a much better position than Clinton was in 2016, for three reasons. First, his performance in polls of swing-state voters is better than Clinton’s was. He’s ahead in Georgia and Arizona, where Trump won last time; he has expanded on Clinton’s lead in New Hampshire and Nevada; and his lead has been more stable in Pennsylvania.

Second, there are fewer third-party and undecided voters in 2020 than there were in 2016. Four years ago, Jill Stein and Gary Johnson rocked the boat by stealing votes from both Trump and Clinton, keeping their vote share below 50 percent. But in 2020, Biden has a majority of voters behind him in national polls, and Trump has fewer persuadable voters to target.

Finally, the race has been less volatile. In 2016, Trump’s and Clinton’s positions in the polls went through wild ups and downs, with Trump nearly catching up or even passing her multiple times. In this race, Biden has kept a steady lead over Trump, and nothing Trump has tried has moved opinion much.

2

Is there anything I can tell about what might happen on Election Day based on the candidates’ schedules?

The coronavirus pandemic and associated limits on candidates’ travel have probably upended the importance of this traditional prognosticating. But what the candidates do in the final days of a campaign can tell you something about campaigns’ internal assumptions. President Barack Obama made a last-minute play for Indiana in 2008 during his first presidential campaign, a sign that the state was tipping toward him in the final stretch. In 2016, Clinton’s campaign belatedly turned its attention to Pennsylvania, a critical state she barely lost. The Trump campaign deployed resources to Minnesota, correctly guessing that the reliably blue state would be close. Even though he lost, they thought it was worth a shot.

David Axelrod, President Barack Obama’s former chief campaign strategist, explains what candidates’ final stops on the campaign trail reveal about the state of a race:

3

What makes this Election Day different?

Virus, virus, virus. The pandemic has had a huge impact on voting logistics. Twenty-three states have expanded mail, absentee or early voting so that people can vote without fear of catching the virus, meaning 84 percent of American voters now have the option to vote by mail. That’s a great thing from a public health and ballot-access standpoint. But it makes vote-counting much more complicated. Many state governments don‘t have a lot of practice counting mail-in ballots, and it could take them a long time to get through the high volume.

Adding to the challenge for understanding what’s going on come election night: Different states start processing ballots they receive by mail at different times, which means they will count and report those results at different dates. Pennsylvania, a critical swing state, won’t begin processing those ballots until 7 a.m. on Election Day itself, and ballots postmarked by Election Day but received within three days after that mean the vote-counting could go on even longer, so if the Pennsylvania results are potentially determinative, they could keep the nation on pins and needles. Two other important states, Arizona and Florida, begin processing ballots 14 and 22 days before the election, which may put them in a better position to count ballots reasonably promptly.

So far, more than 60 million people have voted early. That’s a huge number, considering more than 138 million total people voted in 2016.

Early vote totals don’t predict results well. But if the early votes keep piling up, we could be in for a high-turnout election.

4

I haven’t voted yet. How can I cast my ballot?

We’re glad you asked! Our colleagues in the Post newsroom have put together an outstanding guide on how to vote, no matter where you live or how you’d prefer to cast your ballot.

María Teresa Kumar, president and CEO of Voto Latino, details how to vote by mail:

5

Is in-person voting risky?

Many states are trying to virus-proof polling places. Most states are requiring or encouraging voters to wear masks; some locales will have curbside voting for maskless voters; and some early voting locations are stocked with hand sanitizer. Large venues, such as Fenway Park in Boston and other sports arenas around the country, have been turned into polling places so larger numbers of people can vote early, and can do so while practicing social distancing.

These measures can’t account for everything: People will show up without masks, and they still have the right to vote, a scenario that could make polling places tense. We can’t make a blanket recommendation about how our readers should vote — everyone needs to consider their health and the health of people they love as they make this decision. But we’re cautiously optimistic about the public health impact of Election Day, as primary voters seem to have avoided causing a major outbreak in the spring and fall.

6

Will I be safe from violence at polling places — or after?

Many Americans have told pollsters that they are concerned about the prospect of harassment or violence at the polls, or in the days following the election. The president has stoked those fears by calling for unofficial polling observers to root out alleged voter fraud and sowing doubt about the outcome of the election. The falsely inflated specter of voter fraud has long been a hallmark of Trump’s campaigns, and he asked for similar volunteers to monitor the election in 2016 — though there were no widespread reports of voter intimidation or violence at the polls in that election.

Still, it’s important to remember: There are a host of laws in place to protect voters’ rights and to prevent intimidation, harassment and violence at the polls. Both the military and law enforcement agencies have been preparing for the possibility of a violent response to the outcome of the election — and for their role in ensuring its integrity.

7

What should I do if someone tries to stop me from entering a polling place or tells me I can’t vote?

If a poll worker can’t find your name on the list of registered voters or says there is something wrong with your registration, you still have options. The laws about how provisional ballots are issued and counted vary by state. But in most states, you should have the right to request a provisional ballot if you encounter any problems inside your polling place, and to get a receipt for that ballot once you hand it back to a poll worker.

Georgetown Law’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection has put together a detailed guide on states’ laws about the presence of armed individuals at polling places, and another summarizing state and local laws governing guns at polling places, the use of intimidating speech and who is allowed to act as an official poll watcher. Both have valuable suggestions for how to document and report potential voter suppression.

8

On election night, when will we start to get results?

Polls close in Kentucky and Indiana at 6 p.m. Eastern, but those are both safe red states, so their results likely won’t tell you much about how the rest of the night is going to go. Florida polls close at 7 p.m., and the real rollercoaster starts then. Pennsylvania and Michigan close their polls at 8 p.m.; Wisconsin and Arizona close at 9 p.m.; and a smattering of Mountain and Pacific states follow as the night rolls on.

Some swing states will report their results quickly, while others could be slow:

- Florida and Colorado have dealt with large volumes of early and mail-in votes. These states may report faster than others, as Colorado starts counting votes as soon as they’re received and Florida starts counting more than a week ahead of time. Arizona shows that practice doesn’t guarantee speed, though. In 2018, nearly 80 percent of voters cast an early ballot, but it still took the state days to resolve the close Senate contest between Martha McSally and Kyrsten Sinema.

- Pennsylvania and Wisconsin won’t start counting mail-in votes until Election Day, and Pennsylvania will keep counting votes received three days after Election Day as long as they were sent in time. Depending on how many voters cast their ballots this way, tallying the vote may take time.

- Michigan won’t start counting votes until 10 hours before Election Day, and the state’s secretary of state is already preparing the public for a delayed result.

- North Carolina counts absentee ballots as soon as they’re received, but the deadline for receiving absentee votes has been extended to Nov. 12.

- Ohio will report results in two waves: According to The Post’s Kate Rabinowitz, officials will publish unofficial results based on their count as of 7:30 p.m. on election night and a count of the remaining absentee ballots, but they will hold off on releasing more results until everything is certified (which could be weeks later).

The margin matters, too. Florida could count its votes promptly and still end up in a protracted recount. And if either candidate achieves landslide margins, that should help news organizations call the race more quickly.

9

Are news organizations planning to report results differently this year?

Yes — much of the news media is attempting to strike a new, cautious tone this year. According to Reuters, top news executives have a “focus on restraint, not speed; on transparency about what remains unknown; and on a reassuring message that slow results don’t signify a crisis.” The goal is accuracy — if a media outlet jumps the gun this year, it will hemorrhage credibility and give Trump the opportunity to call the entire election “rigged.”

Many news outlets are also changing the way they track results. For example, according to Axios’s reporting, NBC News will only use statistical models and only project races when “99.5% confident” in the result. The New York Times has already said the paper might not be able to name a winner in key states and is focusing on presenting uncertainty. CBS News will use exit polls, its own surveys and vote totals to show how states are trending in real time.

Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, says don’t pay attention to cable news election-night coverage until results start to come in:

10

What about exit polls? Will they give us an early peek at who won?

Not really. Exit polls are a tool that news outlets use to call races and get an early look at voter demographics. Edison Research, the company that conducts the exit poll used by ABC, CBS, CNN and NBC, not only interviews voters as they leave polling place but also calls voters who cast mail ballots and tries to reach early voters as well.

Any exit polls you hear about early in the evening likely won’t tell you whom voters say they backed in the voting booth. Instead, they’ll sketch a portrait of which demographic groups turned out and which issues they say were important to them.

[David Ignatius: How news networks are preparing for the possibility of a delayed vote count]

In any case, especially in the early hours of election night, you should mostly ignore them. In 2004, respected pollsters, members of the national media, the top brass in John Kerry’s campaign and even Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) all read too far into the early exit polls and prematurely crowned Kerry the winner.

Once the election is over, exit polls can help us figure out who voted for whom and why. But even then, they’re not flawless. In 2016, they overestimated the share of White college-educated voters in the electorate.

Stephanie Schriock, president of Emily’s List, says ignore the exit polls:

11

What states and regions should I watch most closely?

Florida. Pennsylvania. Michigan. Wisconsin.

Those are the most likely “tipping point” states that could deliver the 270th electoral vote to Trump or Biden.

Within those states, watch the cities. Clinton could have won the White House in 2016 had she managed to increase Black turnout in major Northern metro areas. Turnout in major cities — as well as Biden’s margin in the suburbs — will matter hugely.

But keep an eye on rural areas, too. If Biden is winning Obama-to-Trump White working-class voters, rural portions of Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Maine and the surrounding states will be a slightly lighter shade of red. In that case, Biden will be in very good shape.

Former House speaker Newt Gingrich advises keeping an eye on North Carolina, Florida, Ohio and Maine:

12

What’s the earliest the race could be over?

In theory, within a few hours. If Biden wins in a blowout in Florida, Trump has very few paths to victory. Similarly, if Biden or Trump is getting a great result in fast-reporting states such as Colorado, there is a pretty good chance the candidate who is performing strongly there is winning across the board.

Networks might not want to officially “call” the race in that case. But viewers could make some strong inferences about who is likely to win.

David Axelrod says the results in Georgia, North Carolina and Florida could signal an early end to the election:

13

What’s the worst-case scenario for the latest we could know who won?

If the vote is close in key states, the election could take weeks or months to be decided and the whole mess could end up in court or Congress.

Still, remember: A delay in finding out the results doesn’t mean the election is illegitimate, just that in a year as strange as this one, it takes time to do things right. Some swing states, such as Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, aren’t used to getting a lot of mail-in ballots. If the race is close, we could be waiting weeks for them to receive and count all their votes.

The 2020 election is also fertile ground for protracted legal battles; in fact, those fights are already underway. More than 200 lawsuits have been filed over mail voting, and disputes over voting procedures and recounts could end up in court after the election.

Court battles may not end up delaying the count. But if we’re talking about worst-case scenarios, these legal maneuvers are definitely worth mentioning, as is the prospect of a battle in Congress over competing delegations of presidential electors.

David Axelrod advises that the time it takes to count mail-in votes may delay a final result:

14

What happens if major news organizations call the election for one candidate but the other candidate declares victory?

In the most literal sense, nothing. National news outlets can declare a winner when enough information is available, but the results need to be certified by states to be official (more on the calendar for certification further down). Political candidates can’t make themselves president by claiming victory, even if it puts them in a better position for an ensuing fight, and the media can’t confer presidential power by correctly reporting the vote count.

If candidates and media outlets clash, consider the competing incentives. News organizations have a strong motivation to avoid the embarrassment of incorrect calls. Candidates who think they can benefit from declaring victory will do so, whether or not they’ve actually won (see the 2020 Iowa caucuses).

15

What down-ballot races should I keep an eye on?

In addition to the presidency, the Senate is up for grabs.

Five races — Colorado, Iowa, Maine, North Carolina and Arizona — will likely decide control of the chamber. Democrats are probably going to lose a seat in Alabama, where Democratic Sen. Doug Jones is lagging Republican Tommy Tuberville, the former college football coach. If Democrats win four of these five seats plus the presidency, they’ll have the 50 votes they need plus Kamala D. Harris as a tiebreaker.

Beyond that, Democrats have made many red-state races competitive. Georgia, South Carolina, Kansas, Alaska, Texas and Montana all feature Republican-held Senate seats where the Democrat has at least some chance of winning. Republicans do have a possible pickup opportunity in Michigan, where John James is challenging low-profile Democratic Sen. Gary Peters. But beyond the core five battlegrounds, the real story is whether Democrats can make inroads into red territory.

In the House, there’s much less to watch. Democrats are strong favorites to retain the majority. The more pressing question is how large the Democratic majority will be. If Democrats expand their 232-seat majority, it’ll be easier for Biden get his priorities through — or impossible for Trump to get anything done. And, in the unlikely case of a 269-to-269 electoral college tie, the contest will be thrown to the House, and the candidate with the majority of state delegations in the new Congress will take the presidency. So the shift of a few seats in a few state delegations could make a difference.

On the state level, there are governor and state legislative races. State legislators elected in 2021 will play a big role in drawing the next round of congressional maps. Texas, Florida, North Carolina and Georgia appear to be the most important states for redistricting, but the battlefield is wide. According to Associated Press’s count, 35 states are holding state legislative elections in which the winners have some influence on the next slate of maps.

Maria Teresa Kumar says watch the state legislatures, especially in Texas and Arizona:

16

Are there important ballot initiatives at stake?

Yes, and some of them may say more about the future of U.S. politics than this highly unusual presidential election.

In California, which by virtue of its size can influence the rest of the country by making state-level decisions about policy, voters will weigh in on whether gig workers should be classified as employees, a decision with enormous implications for companies such as Lyft and Uber. The state’s voters are also considering whether to permit the use of affirmative action in school admissions and in hiring, overturning a ballot initiative that banned the practice in 1996, and whether to end cash bail for criminal defendants.

Other big issues are on the table, too. Five states are grappling with whether to change their laws around marijuana possession and use. Mississippi voters are deciding whether they like their new state flag, a design change prompted by a reckoning with slavery and racism in the state. Florida is contemplating raising its minimum wage. And that’s just a start. One of the best ways to distract yourself while waiting for states to be called is to dive deep on these other measures, which function as a preview of major political debates to come.

Grover Norquist says ballot initiatives are the secret key to understanding voters:

17

When will the result be official?

In a typical election, the answer to that question doesn’t really matter. The process for making the results “official” is largely ceremonial, and that remains the most likely outcome.

But there’s always the chance of chaos. In that case, the following dates will be important:

Dec. 8 is the “safe harbor” date by which states can name their slate of electors to the electoral college without being second-guessed by Congress. (States must use laws on the books by Nov. 3 — no changing the rules for counting ballots after they’ve been cast.)

If states miss the “safe harbor” deadline, they still have six more days to finish counting ballots and appoint electors based on that count, but they lose the benefit of the congressional pledge not to overturn the state’s own tally. Even so, as long as the states collectively nominate 538 electors that represent the popular result, with one candidate securing 270 electoral votes, the suspense should end here.

If, on the other hand, there are competing claims about who won a state — and competing slates of electors — things get messy.

On Dec. 14, the electoral college votes. This is usually a formality. But it’s possible that state officials of different parties — say a Democratic governor and a Republican state legislature in Pennsylvania — will submit different slates of electors. That would replicate what happened in the disputed Hayes-Tilden election of 1876, when rival slates of electors sent to Congress their conflicting submissions, each claiming authority under state law.

Then, on Jan. 6, 2021, the sitting vice president announces those votes to Congress, certifies the result, and names the president-elect and vice president-elect. Again, this process is ordinarily straightforward. But if the election is still disputed at this point, with one or more states submitting conflicting electoral votes, the law could get alarmingly fuzzy.

The outcome is up to the new, just-elected Congress, but with Vice President Pence as the presiding officer. Under the applicable statute, Democrats would be able to elect Biden if they controlled both houses of Congress. Republicans would elect Trump if they had both chambers.

But if neither party has a majority in both houses of Congress, we could end up in a difficult situation. Imagine that a Republican Senate accepts a slate of Trump electors from Pennsylvania, but a Democratic House says Biden won the state and accepts his electors.

Could Pence decide that Pennsylvania’s votes don’t count and that therefore he and Trump have been reelected by a majority of the remaining electoral votes? Could he simply declare that Pennsylvania’s votes went to Trump-Pence and that they have therefore been reelected?

In short, it is possible to end up in a situation where both candidates have a plausible claim to the presidency — and what happens then is unknown. Still, this scenario is unlikely. Instead, the winner will probably sail through these dates and officially take the oath of office on Jan. 20 — and the 2024 campaign will begin.

Read more:

David Byler: Nobody can predict this election. Here’s why.

All of the Post Editorial Board’s endorsements in 2020 races

These people told us in 2016 why they voted for Trump. Here’s how they’re voting in 2020.

Read the latest edition of the 2020 Post Pundit Power Ranking

“