What you need to know about Dominion, the company that Trump and his lawyers baselessly claim ‘stole’ the election

Egged on by Trump-friendly One America News and lawyers Rudolph W. Giuliani and Sidney Powell, the president has accused Dominion of deleting votes for him with a system that is “horrible, inaccurate and anything but secure.” Trump’s advisers also claim Dominion’s software was created at the behest of former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez to win that country’s elections.

While there’s no evidence for any of those accusations — The Post’s Fact Checker debunks the alleged ties to Venezuela in detail — they’re bringing fresh attention to the way U.S. elections are run and to private companies like Dominion that have long played a starring role in the process. They’ve also deeply unsettled cybersecurity and election administration experts, who worry that valid concerns about election integrity are now being overshadowed by claims that have no basis in reality.

The bottom line is that private companies do play a huge role in running elections in the United States, and observers across the political spectrum have complained about it for years. But that doesn’t mean that any votes have been stolen. Here’s what you need to know.

What is Dominion, and how long has it been around?

Dominion Voting Systems was founded in 2003. It started out as a Canadian company and was later incorporated in the United States; it now has offices in Denver and Toronto. The company offers software and hardware for elections, including computer programs to manage databases and election audits, touch-screen voting machines, ballot scanners and ballot printers.

Jurisdictions across the United States have used the company’s products, some for years. Dominion says it serves more than 40 percent of American voters and that its products are used in 28 states.

Alongside Dominion, which did not respond to requests for comment for this story, two other companies help administer most elections in the country: Election Systems & Software, which is based in Omaha, and Hart InterCivic, based in Austin. All three companies are privately owned.

What kinds of voting products does Dominion make, and where are they used?

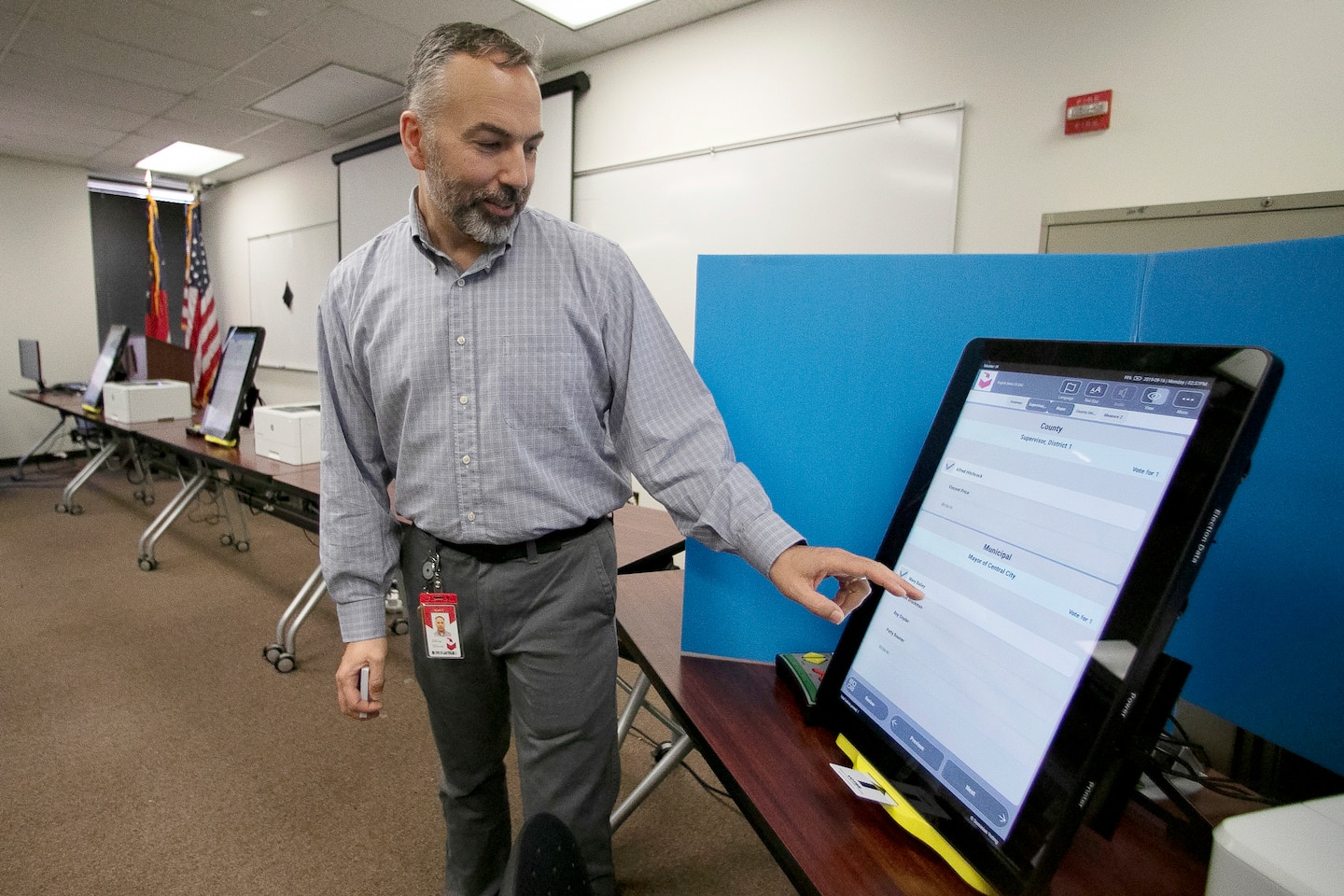

Dominion’s main voting machine offering, like that of most of its competitors, is called a ballot-marking device. Voters mark their choices on a touch screen, and when they’re finished, the machine spits out a paper record with a summary of their selections. Voters then feed the paper into a scanner so their vote can be tabulated. The company makes a couple of different variations of this machine, branded as the ImageCast. In one variation called the ImageCast Precinct, the scanner and the touch-screen machine are combined into one device.

ImageCast machines are used to varying degrees in more than half a dozen states. Georgia, one of the few states that buys election equipment centrally rather than leaving the decision up to each county, spent more than $100 million to deploy the ballot-marking devices statewide beginning last year. Colorado also uses ImageCast machines statewide, though only a small fraction of voters cast their ballots this way because most Coloradans vote by mail.

In many other election jurisdictions, including some counties in California, the majority of voters use hand-marked paper ballots when they vote, but there is one ImageCast or similar machine per precinct to accommodate voters with disabilities or language needs.

Trump allies have claimed that Dominion products are concentrated in states that went for President-elect Joe Biden, but that’s not true. Some counties in Florida use ImageCast machines, for instance, as well as election management software offered by the company. Utah’s largest county also uses Dominion products.

What do we know about the security of Dominion’s voting technology system?

Dominion says its equipment goes through multiple layers of security checks. The company also says that its ballot-marking devices are just as secure as hand-marked paper ballots because they produce a paper record that can be used to audit an election afterward.

Cybersecurity experts aren’t so sure. They say it’s still possible for a bad actor to manipulate the machines so that the paper that gets printed doesn’t actually reflect a voter’s true selections. To make matters more complicated, the paper records produced by some ballot-marking devices — including the ImageCasts used in Georgia — convert voters’ choices into a bar code, which is what gets scanned to tabulate their vote. Computer hackers could manipulate those bar codes, too, experts say. (The company calls that an unlikely scenario and reiterates that its products have passed security tests performed by independent, federally accredited laboratories.)

Whatever the risks may be, though, scientists and election administrators all agree that there’s no evidence any such risks have been successfully exploited during the November elections.

How can we square concerns about voting technology integrity with the claims that Trump and his allies are making?

Wenke Lee, a computer science professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, puts it this way: If your home has a security system, it’s probably not foolproof. “Does that mean that yesterday somebody broke into your house? Come on,” he says. Lee and many other cybersecurity experts who argued against Georgia’s purchase of ballot-marking devices say the current allegations made by Trump and his allies have no merit.

“Scientists like me have been warning for literally years and years that computer voting machines pose cybersecurity risks,” said Alex Halderman, a University of Michigan computer science professor who is in the middle of reviewing the security of Dominion’s electronic voting system in Georgia. “All of that is very different from drawing the conclusion that the 2020 election was rigged, which is an absolutely extraordinary claim.”

Concerns about touch-screen voting devices aren’t isolated to Dominion. The other two leading voting technology companies supply similar machines to jurisdictions across the country, including places that voted for Trump. Many counties in Texas use machines from Election Systems & Software, for instance, and some of those machines don’t produce any kind of paper record at all.

“It’s an industry-wide concern,” Halderman said. “There’s no logical reason to be singling out one company.”

Halderman also argues that if Republicans were really concerned about election integrity, they would have more seriously considered comprehensive legislation aimed at fixing the problem. Instead, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has consistently blocked it.

What does the company say in response to Trump’s claims?

Dominion says none of Trump’s claims — some of which it has responded to on its website — have any merit. “Conspiracies about @dominionvoting seem to grow more bizarre each day,” the company wrote in a tweet Wednesday linking to its response. The next day the company tweeted, “Assertions about vote deletion & switching are completely false.”

Dominion has also pointed to assurances from local and federal election officials that there is no evidence that any voting system was compromised during the election. “There is no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised,” reads a statement from a coalition of federal cybersecurity officials, local election administrators and voting technology companies.