As an educator, I qualified for the vaccine. Why did I feel so guilty getting it?

Instead, I felt a swirl of emotions: privileged, blessed and guilty all at once.

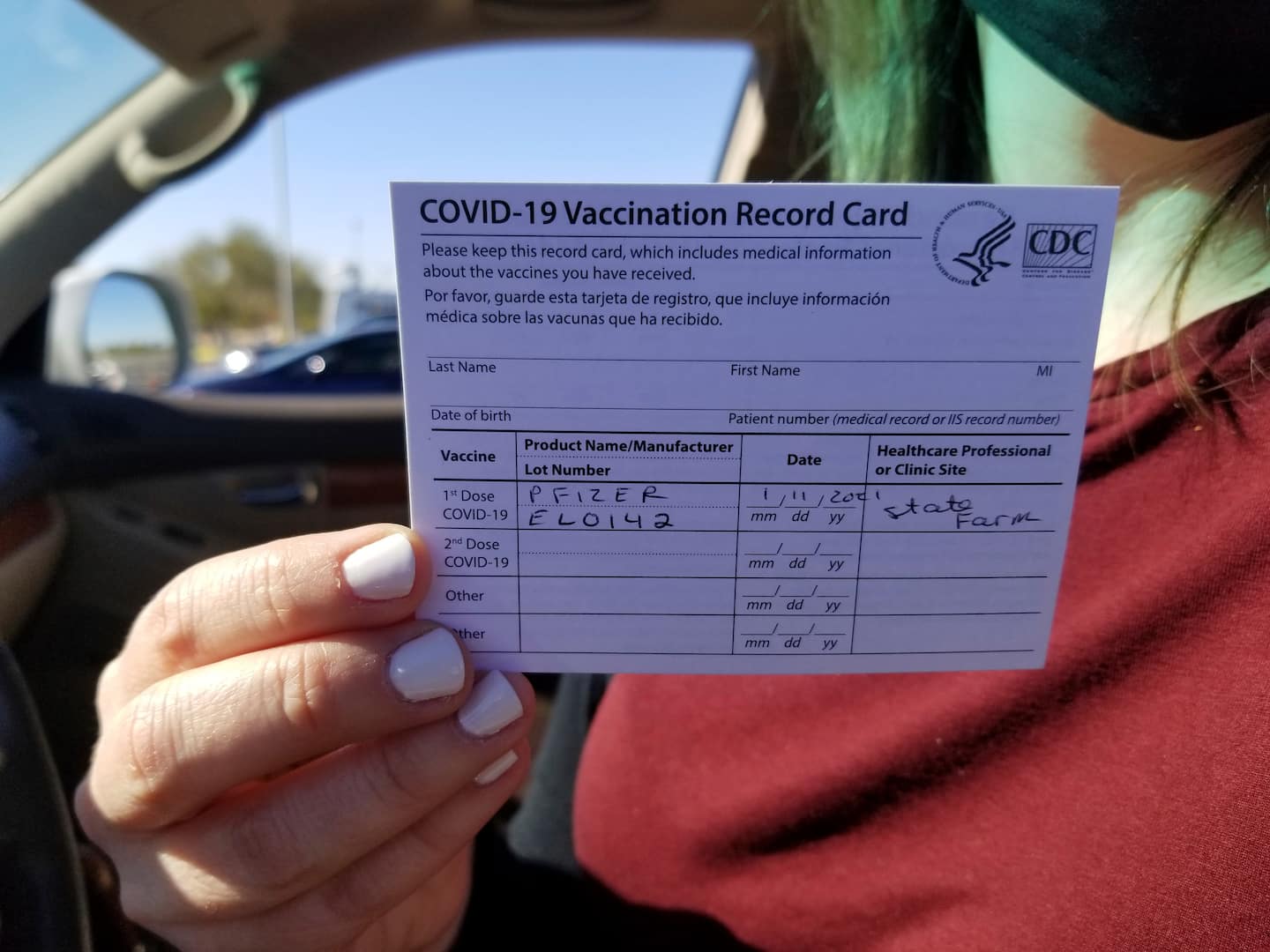

I am 47 years old and in good shape. My blood pressure, cholesterol and vitamin levels are fine, and I have no conditions that would put me at an increased risk of serious illness if I contracted covid-19. Yet there I was on a recent crisp Sunday afternoon, receiving my first dose of the vaccine.

It weighed on me that I was getting inoculated against the coronavirus ahead of my loved ones in covid-ravaged Brazil, including my mother, a breast cancer survivor; ahead of my sweet septuagenarian neighbors who work six days a week at the Thai restaurant they own; ahead of tens of millions of other at-risk adults.

As a college professor, I qualified for the shot. Since August, I have been teaching in person, riding the wild rise of covid-19 infections in a state that, as of Saturday, ranked first in the nation in new cases and average daily deaths over the previous seven days.

In an advisory memorandum released as the fall semester resumed, the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, an arm of the Department of Homeland Security, included “professors, teachers, teacher aides, special education and special needs teachers” in its list of “essential critical infrastructure workers.” It highlighted our role in ensuring the “continuity of functions critical to public health and safety, as well as economic and national security.” I bet a lot of working parents agree that schools are also critical to the optimal functioning of families.

I got to the front of the line because Arizona chose to prioritize educators. During a December news conference, Gov. Doug Ducey (R) ranked us amid front-line health-care workers, doctors, nurses, residents of long-term care facilities and law enforcement officers. “We want our schools open and our teachers protected,” Ducey said.

This almost made me forgive him for failing to enact a statewide mask mandate — which Arizona still lacks — and for the months last spring when Ducey prevented communities from enacting mandates of their own. He told a local radio talk-show host this month that the vaccine is “the first solution that has presented itself” since the pandemic took hold nearly a year ago. But I wonder how many lives might have been spared had he spent the year vigorously pushing proven mitigation measures.

Too many people have died. Many more will die or fall gravely ill from the virus because, for too long, politics have been allowed to dictate how we’ve faced a public health crisis. I have lost loved ones. Others I care about have been infected and are living with aftereffects of covid. One of my uncles in Brazil spent a week on a ventilator and is too weak to walk more than a few steps on his own. I don’t know when it will be safe to visit my parents, whom I haven’t seen in a year.

After I was vaccinated, I sat for 15 minutes in my car, as instructed, in case of adverse reactions. While I waited, I called my mother. “I’m worried that I may have taken a dose of the vaccine away from somebody else who needs it more than I do,” I said. “Eu não sou médica,” she told me in Portuguese, our shared language. I’m not a doctor. “But when educators protect themselves, they’re also protecting their students, and that’s very important.”

Part of me knows she’s right. I have worked hard to protect my students — at least those who have shown up in person for classes. Counterintuitively, more are attending in person this semester than last, even though the daily number of new coronavirus cases in Arizona was long a small fraction of what it has recently become (6,706 on Tuesday). I wear three-layer masks, disinfect everything on my desk before and after class, and try to keep my distance when students follow me outside, asking questions.

My students are anxious. We all are. In Arizona, vaccine demand is overwhelming and supply is limited. Appointments fill up swiftly. The state’s registration website is tough to navigate; those trying to call have had to wait hours to get through.

When I told my students that I had gotten the first dose of the vaccine, they congratulated me. They were happy for me. I was too — mostly.

Read more: