Black history is often shunned — like the book I wrote

Martha S. Jones, a historian at Johns Hopkins University, is most recently the author of “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.”

When I wrote a book about Black women’s long struggle for voting rights in the United States, I knew the story was partly about how racism has shaped our democracy. I never expected that a public library today would refuse to host a discussion featuring my book.

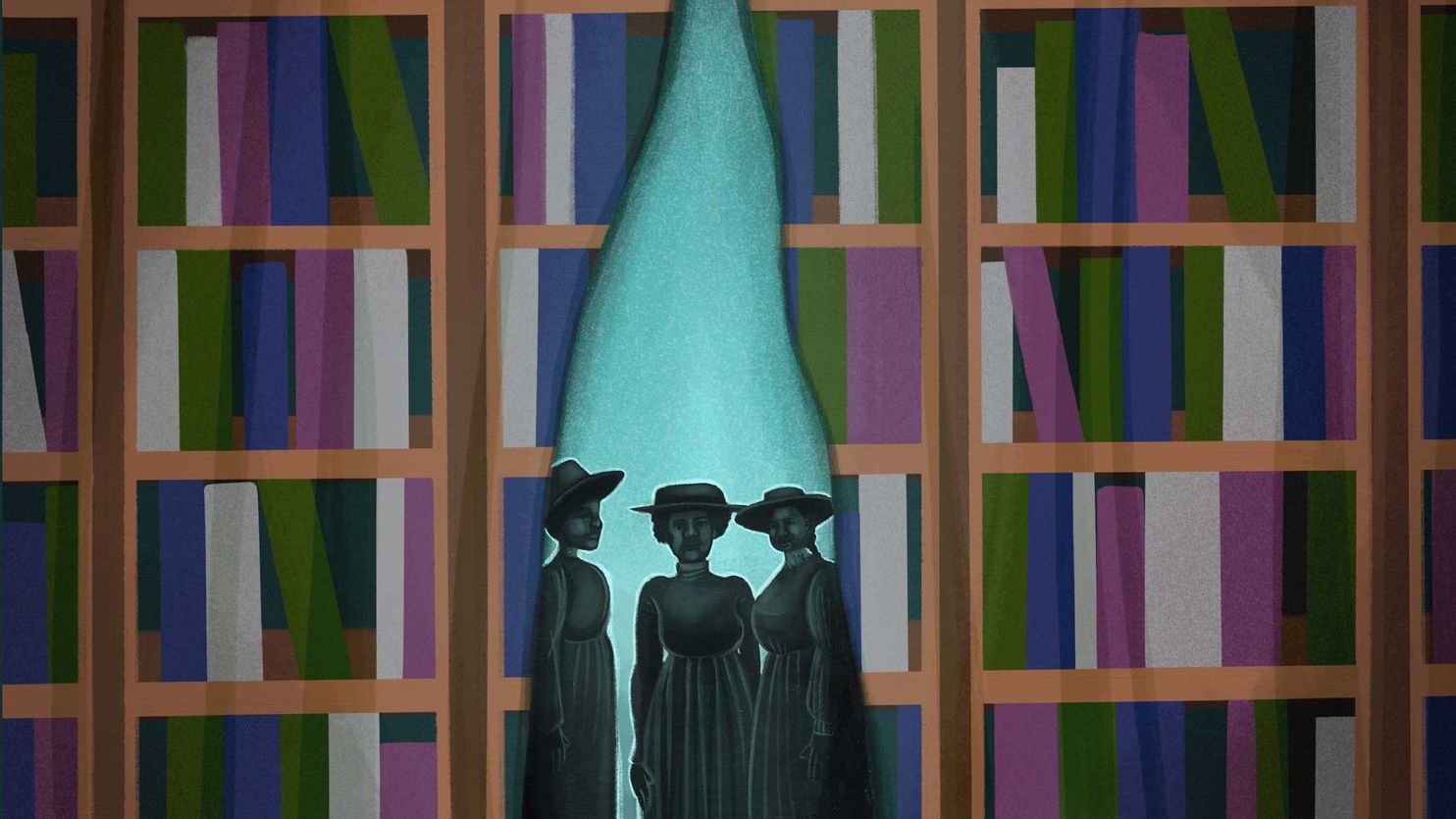

“Vanguard” recounts how many suffragists and lawmakers who sought to ratify the 19th Amendment accommodated and, in some cases, embraced anti-Black racism even as they worked to expand access to a fundamental democratic right. Jim Crow laws — poll taxes, literacy tests and more — prevented Black women from casting ballots for decades after the 19th Amendment became law in 1920.

Facing these ties between racism and democracy can be difficult. People forget that history is not merely a recounting of past events but also a battle over who writes it, from which perspective and what those stories teach about who we are as a nation.

After my book was published in September, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities invited me to give a lecture in connection with an educational initiative on the history of voting rights and voter suppression. My book was to be featured with five others, including “Bending Toward Justice,” a study of the 1965 Voting Rights Act by Gary May. I jumped at the chance to talk about the women of “Vanguard” in cooperation with the state’s public libraries, which make learning free and accessible to all.

Late last year, the endowment invited the Lafayette Parish library board to join its initiative — called “Who Gets to Vote?” — and offered it a $2,700 supporting grant. In December, the board approved applying for the grant — with conditions. To ensure that the program and library “remain apolitical and neutral” and to “garner community support,” a board member suggested adding “two speakers from opposing sides to offer differing perspectives.”

My book, I was sure, fit the bill. It recounts the clashing perspectives that animated voting rights struggles: suffragists against anti-suffragists, white supremacists vs. anti-racists, women countering men, and Americans opposing others of different color. What precisely troubled the board? “Vanguard” foregrounds the Black women who, for 200-plus years, struggled to expand access to political rights for all. It argues that they are among the architects of American democracy.

The library board ultimately voted Jan. 25 to reject the grant, effectively refusing to host a community discussion on voting rights. The board’s president cast the decision as an effort to “bring political neutrality back to our Library System,” saying in a statement that the local presenters “were clearly from the same side of the political debate.”

I’m not sure precisely what debate the board had in mind.

One state senator ventured an answer, explaining: “The question was raised as to the other side being represented and part of the discussion. … [T]he other side falls in the category of ‘Jim Crow Laws’ and the ‘KKK.’ ”

History is more than a matter of academic debate. Events over the past year — including pushback against the New York Times’s 1619 Project and counterprotests to the Black Lives Matter movement — illustrate the fraught challenge of unearthing racism in America, past or present.

Nor is suppression of reading material a relic of the past. The American Library Association tracked 377 “banned and challenged books” in 2019. Among these are works on the history of racism and some that take the perspective of Black Americans. Authors include David W. Blight, Lerone Bennett Jr., John Hope Franklin, Gerald Horne, Robin D.G. Kelley, Gerda Lerner, C. Eric Lincoln, Clarence Lusane, Tim Madigan, Jonathan M. Metzl, Daniel J. Sharfstein and Joy Ann Williamson. There’s one by my former teacher, the late Manning Marable. The list even includes Harriet Jacobs’s “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” a firsthand account published in the 1860s.

This list is a grim reminder that Black history — its ideas and the books that contain them — is still often unwelcome. The subject rankles officials such as those in Lafayette because it is inextricably tied to ongoing striving for freedom, equality and the just acknowledgment of the perspectives of Black Americans.

“Vanguard” shows how Black women put provocative ideas to paper even in the face of marginalization and violence. Throughout American history, Black women have aimed to be of consequence. They knew that with the capacity to publish their ideas came the power to make change. They mobilized the past to create a new future. Black History Month may be a time to acknowledge the many suppressed works on African Americans — and to reflect on how history arms us to challenge racism in the present.

Read more:

Michele L. Norris: Don’t call it a racial reckoning. The race toward equality has barely begun.

Martha S. Jones: Black women in politics are no longer a ‘first.’ They are a force.

Elizabeth Cobbs: What took so long for women to win the right to vote? Racism is one reason.