Affluent professionals and unions: Can this marriage last?

Rereading Teixeira and Abramowitz today, one is struck by their eerie prescience, but also by the fundamental difficulty of holding together a Democratic Party where highly educated and affluent adults are the ascending faction but are not numerous enough to carry an election by themselves. This past year, that difficulty has come into sharp focus as the pandemic has set the educated class that leads the party on a collision course with its traditional union base.

That crash might have come sooner if private-sector unions hadn’t been largely a spent force. If White manufacturing workers and manual laborers had remained the party’s “prototypical” voters, as Teixeira and Abramowitz say they were in the mid-20th century, one can imagine that shift of the highly cosmopolitan “mass upper middle” toward Democrats might have stalled over issues such as immigration and trade.

These days, however, “labor” is more likely to mean government unions, which account for a slight majority of all unionized workers. Public-sector unions aren’t worried that the local school system is going to outsource its teaching to China or that courthouse jobs will be taken over by immigrants from Guatemala. So the party could keep singing the same hymns to organized labor even as the congregation turned over and its theology changed.

Progressive professionals might not like every single thing the teachers unions or the transit workers did, but they could live with it — and if services became really intolerably bad, they moved someplace where the unions were less intransigent, even while insisting that they were very supportive of public services, and of a well-paid government workforce represented by government unions.

The death of George Floyd, however, made it a little bit harder to voice full-throated support for government unions. Progressives raged at each new revelation of how insulated police officers had been from any sort of accountability for abusing their power. They had a whole bevy of union-negotiated special protections that made it hard to convict bad cops, and just as hard to separate them from the force.

When progressives pointed out, correctly, that this was an outrageous abuse of the public trust, the responses from the police unions tended to fall between unrepentant and obnoxious. For the first time, one heard good lefties discussing abolishing a public-sector union, or at least sharply curtailing its bargaining rights so that public safety would be the priority, rather than guaranteeing police jobs.

When conservatives pointed out, somewhat acerbically, that they’d been calling for the abolition of government unions for decades, those progressives explained that police unions were a unique case, and they still wholeheartedly supported good government unions like teachers unions, which would never put the welfare of their members above the good of the children. Democratic coalition saved.

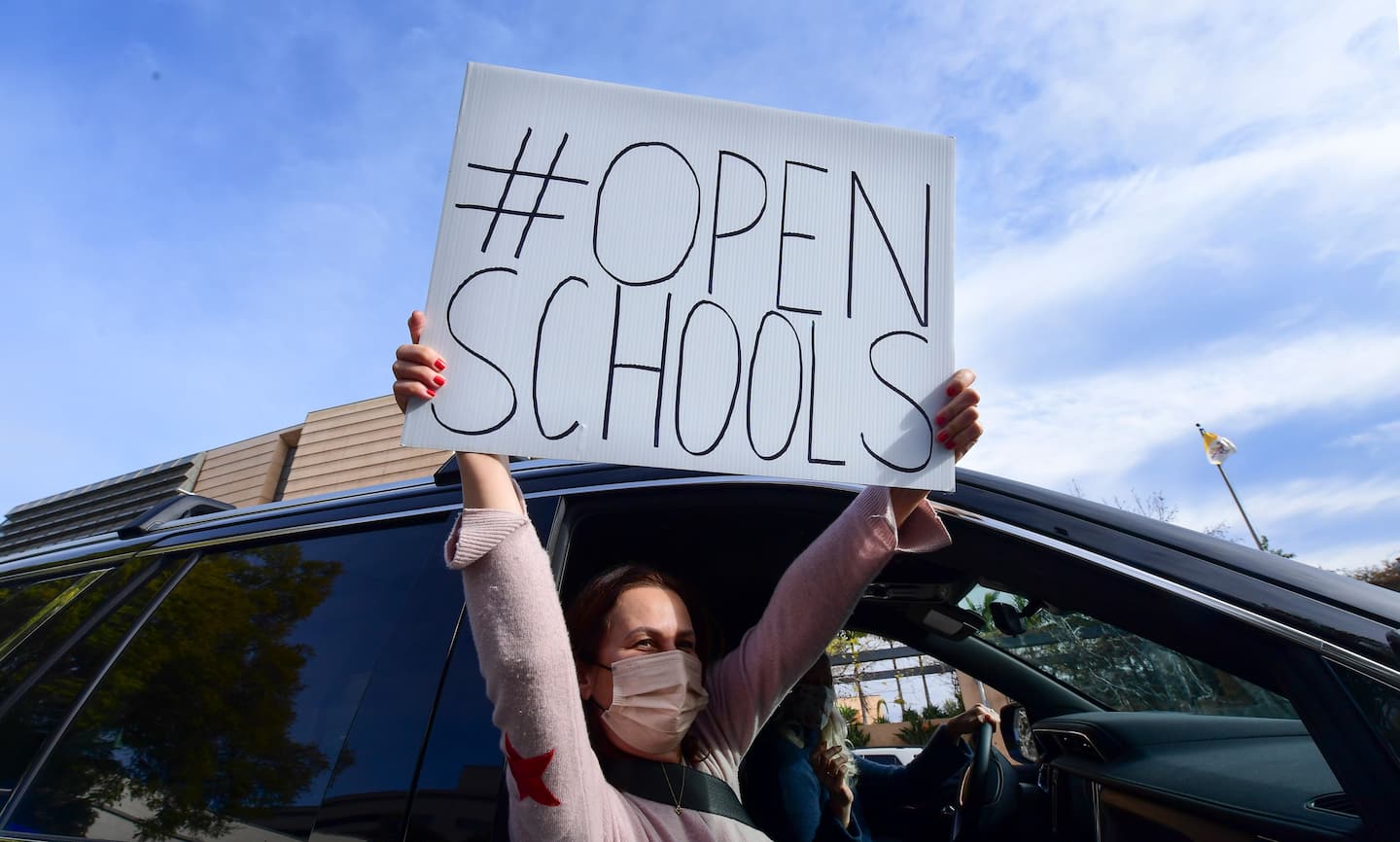

Then blue-state school districts tried to reopen. The teachers unions balked, or rather made demands so extensive that they could not possibly be accommodated in any reasonable time frame. In districts where the schools are run by school boards, elected in low-turnout, union-dominated elections, the schools stayed closed. And one started to hear a lot of people saying, “Of course I support teachers unions, but….”

Yet even those critics couldn’t quite bring themselves to acknowledge what was happening: Unions were advocating for policies that might lower what was already a small risk to their members even though this effectively meant millions of children would fall even further behind in their schooling while parents struggled to work. They were doing this not because they had irrational fears that could be explained away, but because they cared more about small risks to themselves than large risks to others, and had made a clear-eyed calculation that they could get away with it.

That’s also what the police unions had done; it is what unions do. If what is best for the employees happens to be good for employers or customers, great, but if it makes them worse off, that’s not the union’s problem. This doesn’t magically change because the “customers” are adorable children and the employers are angry taxpayers. In fact, the self-dealing gets worse, because unlike their private-sector counterparts, government workers get to vote for their bosses. Also, since their employer basically can’t go out of business, they worry somewhat less about keeping their demands reasonable.

The pandemic has made this fact too apparent for progressive parents to ignore — and moreover, it has done so in the one area where they are just as fanatically inflexible as the unions. It’s not clear how those erstwhile allies will resolve this quandary — or how the Democratic Party will win elections if they can’t.

Read more: