To understand contemporary American culture, look to Marvel Comics’ Stan Lee

Lee understood better than anyone that the true power of Marvel’s comics wasn’t their jolting artwork or snappy wordplay but the sense of community these books created. His genius lay in the sense of intellectual adventure he was able to cultivate by traveling campus to campus convincing young adults that his funny books were art on par with the European filmmakers then in vogue. His efforts laid the groundwork for today’s hyper-engaged fan culture and might be a more important innovation than the origin story for any character ever could be.

The dispute over Lee’s legacy stems from the “Marvel Method” in which artists drew stories from a rough plot, while the writer filled in the word bubbles with dialogue. This allowed greater freedom of artistry while freeing up writers and artists alike to work on multiple titles at once. The writer in this crucial period generally was Lee, born Stanley Lieber, the son of immigrants who served in the Army’s propaganda department and worked in the world of comics for most of his adult life.

The artist was often Jack Kirby, whose kinetic artistry and blocky, less realistic depictions of hero and villain alike gave Marvel a weird energy heretofore unseen in the world of comics. Where things get tricky is that, as years passed, Kirby would dispute that Lee created the famed characters who made up the core of the Marvel stable, insisting he was the plotter as well as the artist. Sure, Lee might have filled in the dialogue bubbles, but Kirby was the one coming up with the stories, creating the side characters and the villains as he went.

Among people who take comics seriously as an art form, Kirby is now considered king and Lee a vapid huckster, a flimflam man whose patois — catchphrases such as “Excelsior!” and “Face front, true believer!” — obscured a lack of creativity. This is not a new fight; I remember hashing these debates out in comic book stores and on early AOL message boards in the 1990s. Abraham Riesman’s exhaustively researched, exemplary new biography “True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee” is firmly in the “fraud” camp.

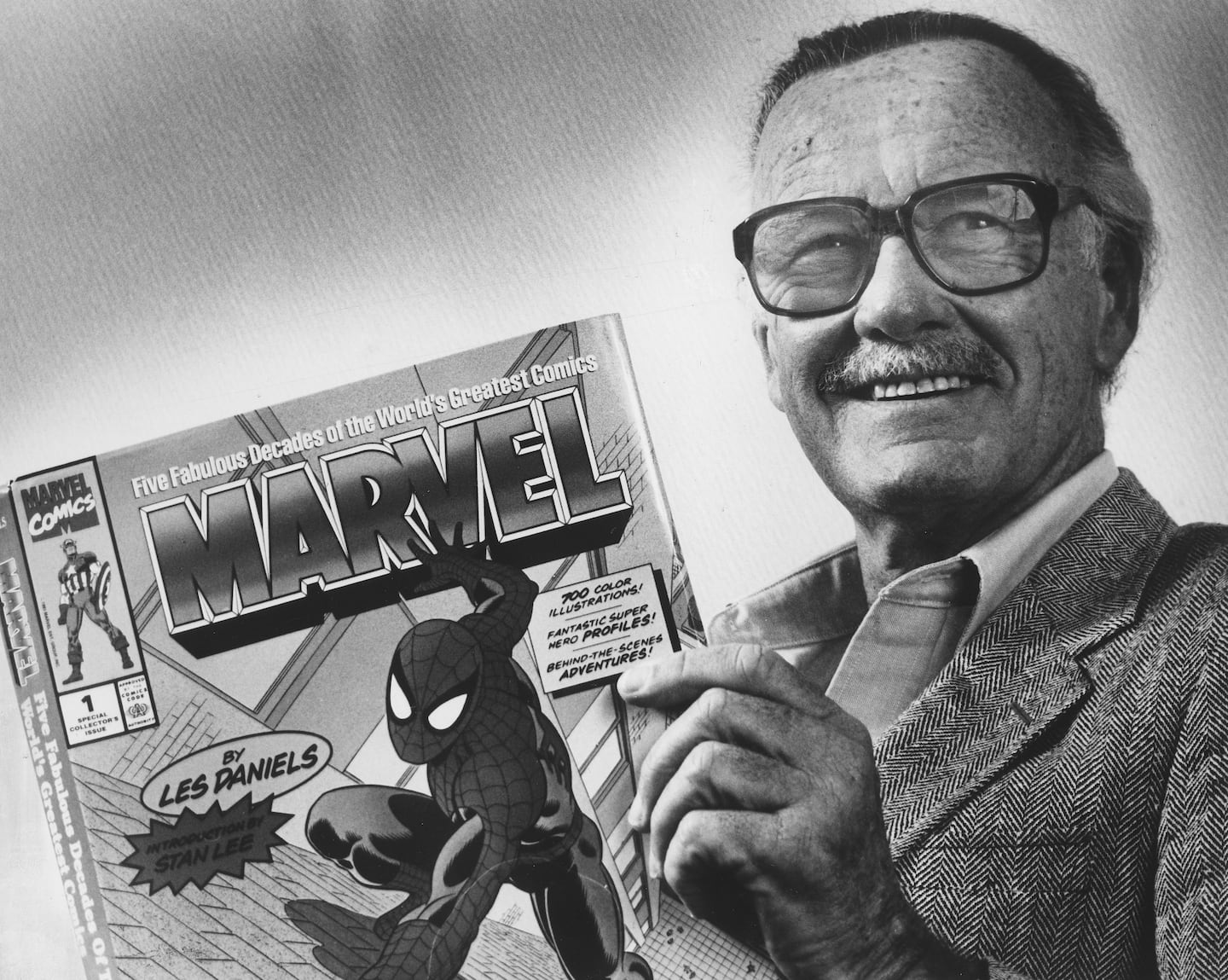

But as comic books have ascended the cultural ladder and become the financial backbone of movies’ theatrical business model, Lee’s supposed misdeeds start to seem like his greatest contributions to the medium’s dominance. Sure, Lee was a hog for credit. Yes, he undoubtedly fed media efforts to make him seem as the brains behind the whole operation. Granted, his appearances on radio shows and on college campuses made him the public face of the burgeoning world of Marvel mania, at Kirby and artist Steve Ditko’s expense.

But in the process, Lee was doing something more important than creating Doctor Doom in issue five of “Fantastic Four” or introducing the world to the Blob in the third issue of “Uncanny X-Men.” He was creating a rabid community of fans and erecting an intellectual edifice that superhero comics to this day rely on for their elevated place in the world.

Riesman highlights an early decision in the letters page of “Fantastic Four” No. 10: From now on, readers were to address the creators as “Stan and Jack,” the informality of it all suggesting a sort of kinship between reader and creator. “Stan was doing his level best to suck them in with witty, engaging copy in his printed publications,” he writes, and this sort of thing was “a delight for a budding geek, what with Stan’s snappy personalized responses to his reader’s missives.”

That cultivation of fandom went hand-in-hand with Lee’s tours of college campuses, which in turn led to pieces of New Journalism in hip journals such as Rolling Stone suggesting Marvel was on a higher level, cerebrally, than previous comics. Lee wasn’t just creating the character of “Stan Lee,” as Riesman suggests. He was also creating a legion of loyal fans, paving the way for the sort of obsessive, aggressive fandom we see from the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s most dedicated patrons today. And he was feeding them intellectual ambitions that suggested the world of spandex-clad bruisers punching each other for our amusement was something worth taking seriously as art.

The last two decades of Lee’s life, captured in heartbreaking detail by Riesman, demonstrate the trap Lee set for himself. He finally achieved worldwide fame via cameos in Marvel movies, yet he was spent as an artistic force, the frontman for a series of creatively bankrupt money pits such as Stan Lee Media and POW Entertainment. The image of a barely conscious Lee being wheeled from convention to convention to scrawl his name on photos to earn a few bucks for a series of malicious handlers and family members is tragic.

In the end, the fight for credit between Lee and Kirby doesn’t matter all that much to anyone other than the estates of Kirby and Lee. The actual characters they created weren’t as important as the idea of fandom that Lee helped inculcate into successive generations of comic book readers. The Marvel Method wasn’t just about mechanizing comic book production and interlocking stories to keep readers hooked month to month. It was about breeding obsession and a sort of arrogance that comes with camaraderie.

No one in the industry has ever been better at that than Stan Lee. Excelsior.

Read more: