Perfect attendance awards no longer belong in U.S. schools

Optimizing attendance has been an understandable concern amid covid-19 shutdowns. An estimated 3 million students nationwide missed school, virtually or in-person, since closures last March — a gap that could have years-long repercussions.

But when attendance is directly tied to school funding — as it is in seven states, including Texas and California — or factored into school quality ratings, it sends the wrong message about staying home when doing so could help stop the spread of germs. As in-person learning resumes, education leaders nationwide need to eliminate school rating and award systems that overly rely on attendance as a measure of success.

In Chicago, which has the nation’s third-largest school district, attendance is the single largest factor — accounting for 20 percent — in the system by which public schools are rated. When in-person learning resumed this month, the elementary schools with the highest numbers of returning students were some of the top-ranked in the district. They have majority-White enrollments, though Black and Latino students account for more than 80 percent of the district’s roughly 209,000 elementary students.

Critics have long charged that Chicago’s ratings system ties school quality to socioeconomic status and race because poverty and illness affect both attendance and performance. (Other ratings factors include standardized test scores, grade-point average and academic growth.) The neighborhoods with the highest-rated schools are also the most affluent. Chicago suspended the ratings system after the pandemic broke out, and the district recently began a series of virtual town halls to develop new metrics, purportedly to be more inclusive.

As officials here and elsewhere evaluate how or whether to use attendance rates to measure performance, educators need to consider not just the ill effects of absenteeism but also the underlying inequity of rewarding or punishing students for factors outside their control.

Students with chronic absences are undoubtedly at greater risk for poor performance and dropping out. Before the pandemic, more than 6.5 million students, or 13 percent of all U.S. children, missed 15 or more days of school each year, according to a 2019 study from the American Academy of Pediatrics that linked chronic absenteeism with poor long-term health outcomes. That’s one of the reasons the academy used to encourage parents to send children to school with the sniffles, a cough, low-grade fever or body fatigue — all symptoms that might now raise a flag for covid-19 screenings.

But targeting attendance so bluntly can have adverse consequences, especially if it incentivizes schools to promote attendance in order to receive funding or achieve higher ratings that can, in turn, bolster enrollment and secure more dollars. Before the pandemic, this messaging also amounted to implicit permission for parents to send sick children to school and potentially avoid the child-care issues raised by keeping them home.

Today, we need policies that encourage decisions based on public health.

To start, perfect attendance awards should no longer have a place in U.S. schools. Such celebrations suggest that younger students have a choice about coming to school when most parents make those decisions. Kids with asthma, diabetes, autism or other developmental disabilities — the children most likely to miss school — are further marginalized by such awards, as are students from low-income families. Requiring doctor’s notes also suggests access to health care is equitable.

Parents and caregivers have explained for months the importance of wearing masks to protect other people and that restaurants, playgrounds and other fun places have been closed to protect the community. This message should be maintained and reflected as in-person education resumes, possibly leading to mask requirements when students or teachers have mundane coughs and colds.

Attendance, of course, is crucial to students’ academic performance. Regular attendance has numerous benefits, including literacy development. But rewarding students for a good immune system or for pushing through illness to be present can be dangerous to individual students and to vulnerable classmates who might be exposed to germs.

Sara Bode, a Columbus, Ohio, pediatrician and member of the American pediatric academy’s Council on School Health, says that traditional awards for perfect attendance “need to change to something more inclusive for those kids with special health-care needs, kids that might be ill more often.” Messaging around attendance should be more targeted, she said. “There needs to be some discussion about illness and how that gets excused.”

Rather than incentivizing schools to reward in-person attendance, funding could be allocated to better support remote learning that would allow students who are home sick to participate.

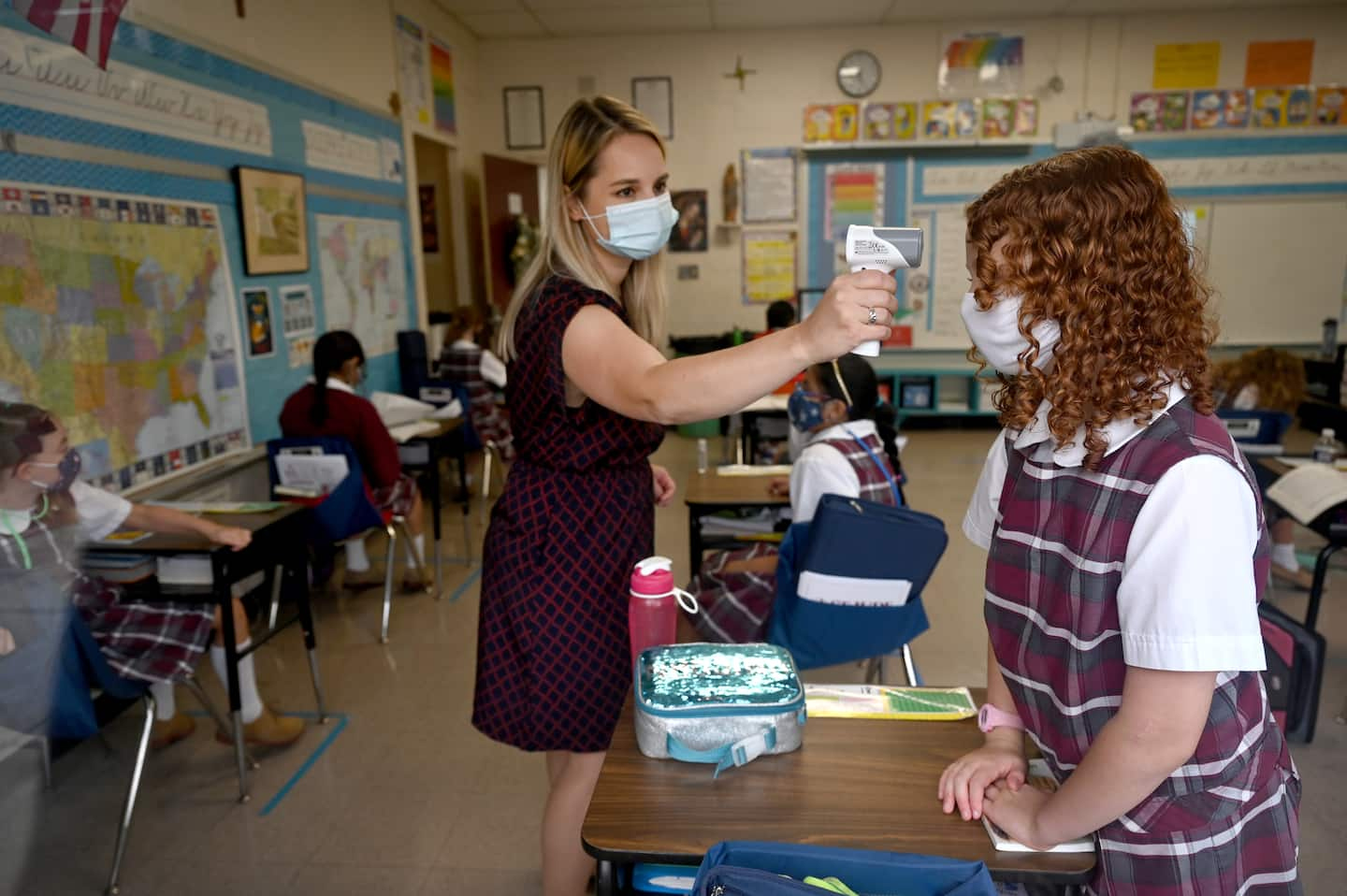

Good health is not a competition. As students return to classrooms with mask requirements and temperature checks at school doors, districts have an opportunity to create policies that stress the importance of public health over individual incentives while still encouraging students to come to school when they are healthy.

Read more: