How America’s surveillance networks helped the FBI catch the Capitol mob

It was too late.

That scene, recorded in a cellphone video Maimone posted to the social media site Parler, helped FBI agents identify the Pittsburgh-area couple and pinpoint their location inside the Capitol, FBI agents said in a federal criminal complaint filed before Maimone’s arrest last month.

Video cameras mounted throughout the complex also captured the pair from 10 different angles, the complaint says, as they allegedly stormed the halls of Congress, rummaged through a police bag and made off with protective equipment that Senate officials kept on hand in case of a chemical attack.

Their case is among the more than 1,000 pages of arrest records, FBI affidavits and search warrants reviewed by The Washington Post detailing one of the biggest criminal investigations in American history. More than 300 suspects have been charged in the melee that shook the nation’s capital and left five people dead.

The federal documents provide a rare view of the ways investigators exploit the digital fingerprints nearly everyone leaves behind in an era of pervasive surveillance and constant online connection. They illustrate the power law enforcement now has to hunt down suspects by studying the contours of faces, the movements of vehicles and even conversations with friends and spouses.

But civil liberties groups warn that some of these technologies threaten Americans’ privacy rights. More than a dozen U.S. cities have banned local police or government officials from using facial recognition technology, and license plate readers have sparked lawsuits arguing that it is unconstitutional to constantly log people’s locations for government review, with scant public oversight.

“Whenever you see this technology used on someone you don’t like, remember it’s also being used on a social movement you support,” said Evan Greer, director of the digital rights advocacy group Fight for the Future. “Once in a while, this technology gets used on really bad people doing really bad stuff. But the rest of the time it’s being used on all of us, in ways that are profoundly chilling for freedom of expression.”

The cache of federal documents lays out a sprawling mix of FBI techniques: license plate readers that captured suspects’ cars on the way to Washington; cell-tower location records that chronicled their movements through the Capitol complex; facial recognition searches that matched images to suspects’ driver’s licenses or social media profiles; and a remarkably deep catalogue of video from surveillance systems, live streams, news reports and cameras worn by the police who swarmed the Capitol that day.

Agents in nearly all of the FBI’s 56 field offices have executed at least 900 search warrants in all 50 states and D.C., many of them for data held by the telecommunications and technology giants whose services underpin most people’s digital lives. The responses supplied potentially incriminating details about the locations, online statements and identities of hundreds of suspects in an investigation the Justice Department called in a court motion last month “one of the largest in American history, both in terms of the number of defendants prosecuted and the nature and volume of the evidence.”

“If the event happened 20 years ago, it would have been 100 times harder to identify these people,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a D.C.-based think tank. “But today it’s almost impossible not to leave your footprints somewhere.”

The federal documents cite evidence gleaned from virtually every major social media service: Parler is mentioned in more than 20 cases, Twitter in more than 60 and Facebook in more than 125. On Snapchat, a woman posted videos “bragging about the attack,” according to one criminal complaint. In another, a man was said to have posted video to TikTok of himself fighting with National Guard members and getting pepper-sprayed.

In at least 17 cases, the federal documents cite records from telecommunications giants AT&T, Verizon or T-Mobile, typically after serving search warrants for a range of subscriber data, including cellphone locations.

Investigators also sent “geofence” search warrants to Google, asking for the account information of any smartphone Google had detected on Jan. 6 inside the Capitol via GPS satellites, Bluetooth beacons and WiFi access points. Investigators then compiled an “exclusion list” of phones owned by people who were authorized to be in the Capitol on Jan. 6, including members of Congress and first responders. Everyone else was fair game.

Federal officials filed similarly broad search warrants to Facebook, demanding the account information associated with every live stream that day from inside the vast complex.

One warrant targeting Brandon Miller, an Ohio man who wrote on Facebook that he had traveled to Washington to “witness history,” yielded his Facebook posts, credit card information, phone number and home Zip code, giving FBI agents the clues necessary to later match his photo to Capitol surveillance camera footage and his Ohio driver’s license.

When Miller was asked on Facebook the day after the riots whether he and his wife, Stephanie, had gotten into trouble, he had written back, “No not yet anyway lol,” a criminal complaint shows.

But data from a Google search warrant allowed FBI agents to map the exact locations of their phones that day — from the point where rioters smashed into the Senate chamber, to the speaker’s office in the heart of the Capitol, according to the complaint. Another search warrant to their cellular carrier, AT&T, added additional information about their whereabouts, plus their names and home address. Stephanie Miller’s attorney declined to comment, and Brandon Miller’s attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

License plate readers and facial recognition software together played a documented role in helping identify suspects in nearly a dozen cases, the federal records show. In many cases, agents used existing government contracts to access privately maintained databases that required no court approval. In several cases, including for facial recognition searches, it’s unclear what software the government used to build the cases for arrests.

The FBI declined to comment for this story. The incidents described remain allegations, with none of the cited cases having been adjudicated yet. In most cases, suspects’ attorneys have not yet filed defenses against charges that in many instances are only a few weeks old, court records show.

Many cases also hinge on imperfect technology and fallible digital evidence that could undermine prosecutors’ claims. Blurry license plate reader images, imprecise location tracking systems, misunderstood social media posts and misidentified facial recognition matches all could muddy an investigation or falsely implicate an innocent person.

Fruitless efforts to hide

Many of the Trump supporters who marauded through the Capitol that day showed little interest in concealing their presence, posting selfies, gloating on Twitter and sharing video of chaotic violence and ransacked hallways. James Bonet, of Upstate New York, uploaded a Facebook video of himself inside the Capitol’s halls, allegedly smoking a joint, a criminal complaint states. And Dona Bissey, an Indiana follower of the extremist ideology QAnon, posted a location-tagged photo of herself and her friends to a publicly available Facebook page: “Picking glass out of my purse,” she wrote, according to a charging document. “Best f—ing day ever!!”

Others, however, attempted to hide their identities and throw off investigators afterward, according to FBI agents’ claims. Suspects covered their faces, switched hats during the day and threatened family members and witnesses to keep quiet afterward, the criminal complaints allege. They deleted social media accounts, hid out in hotels or ditched potentially incriminating phones, according to the documents. One suspect stopped using a car he feared might be on authorities’ radar, the federal documents show, while another said he “fried” his electronics in a microwave. The FBI’s surveillance efforts found them anyway.

One man from New York’s Hudson Valley, William Vogel, had his round-trip voyage to D.C. photographed by license plate readers at least nine times on Jan. 6, from the Henry Hudson Bridge in the Bronx at 6:06:08 that morning to Baltimore’s Harbor Tunnel Thruway at 9:15:27 a.m. and back to the George Washington Bridge in Fort Lee, N.J., at 11:59:22 that night, a criminal complaint claims.

Vogel generated more evidence of his presence inside the Capitol with a set of videos he posted to Snapchat, the complaint said. And though no license plate scanners captured his car in D.C., they offered other clues to his movement: A photo that morning from a stretch of Interstate 95 northeast of Baltimore showed a comically oversized “Make America Great Again” hat on Vogel’s dashboard. Agents said in the complaint that they later matched it to a Facebook selfie in which he appeared to be wearing “the same large red hat.”

Installed on thousands of streetlights, speed cameras, toll booths, police cars and tow trucks across the United States, the scanners record every passing vehicle into databases run by contractors such as Vigilant Systems, which reports that it has recorded 5 billion license plate locations nationwide. In Maryland alone, government and police scanners captured more than 500 million plates last year, state data shows.

Dominick Madden, a New York City sanitation worker who was on sick leave when he allegedly stormed the Capitol, had his car’s license plate scanned half a dozen times in his round-trip journey to Washington, a criminal complaint states. Madden was also allegedly caught on video walking through the Capitol’s Senate wing in a blue QAnon sweatshirt. He has pleaded not guilty, and his attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

In many cases, the documents quote suspects expressing confidence that they had slipped beyond the FBI’s grasp. When an unnamed Parler user warned Maimone — the Pittsburgh-area woman with the American flag mask — that authorities would be arresting anyone who entered the Capitol building illegally on Jan. 6, she dismissed the idea through her account, “TrumpIsYourPresident1776.”

“Lmao yaaaaaaaaaa sure thing buddy!” she wrote in an exchange cited in the criminal complaint charging Maimone with theft, violent entry and disorderly conduct on Capitol grounds. A D.C. judge signed a warrant for her arrest last month.

FBI agents got help identifying Maimone and her fiance, Philip Vogel (no known relation to William Vogel), by manually comparing his voice and hand tattoos to a Pittsburgh TV news report from last year, during which he talked of being rescued one night after his fishing boat hit a log and capsized, the federal complaint said.

Investigators also matched Vogel’s gray beanie to a photo he and Maimone had posted to the Yelp profile of their contracting business, according to the complaint. And they matched his scarf to one he’d worn in a selfie posted to his Facebook account in which he celebrated catching a “monster” fish in the Potomac River one day after the riot.

Attorneys for Maimone and Vogel declined to comment. The couple have been released from custody after they each paid $10,000 in bond and agreed to “stay away from D.C.,” court records show.

Other alleged insurrectionists ended up helping investigators even as they attempted to cover their tracks, FBI agents wrote in charging documents. One man entered the Capitol wearing a dark cowboy hat and a large respirator that covered all but his eyes and forehead. But he also took a selfie beneath a marble statue of the nation’s seventh vice president, John C. Calhoun, a fixture of the large “crypt” room beneath the Capitol Rotunda. A tipster who received the photo forwarded it to the FBI, a criminal complaint said, along with a suggested name: Andrew Hatley.

Hatley denied participating in the attack, writing on Facebook: “It has come to my attention that there was someone who looks like me at the Capitol. I’d like to set the record straight. I don’t have that kind of motivation for lost causes. I just don’t care enough anymore, certainly not enough for all that.”

But he allegedly left evidence to the contrary in the logs of a social media app, Life360, often used by family members to keep track of each other. When a tipster told FBI agents that Hatley had the app on his smartphone, they sent a search warrant to Life360 days after the attack. Investigators said in the complaint that they then plotted Hatley’s travels on “an electronic map of Washington, D.C.” based on the company’s logs.

In the just-the-facts style of FBI documents, investigators alleged the evidence erased any doubts: “The data confirms that HATLEY’s cellular telephone was at the U.S. Capitol Building during the events described above on January 6, 2021.” Hatley’s attorney and Life360 declined to comment.

In another case, an FBI agent wrote in a criminal affidavit that a “self-professed white supremacist” from Maryland, Bryan Betancur, had asked his probation officer for permission to leave the state on Jan. 6 to hand out Bibles in D.C. with an evangelical group. But Betancur’s court-ordered ankle monitor gave him away, the affidavit claimed, by posting his minute-by-minute location — from Trump’s rally at the White House Ellipse to the Capitol’s steps — to a website investigators could track in real time. He was arrested on Jan. 17, nine days after he told his probation officer he believed the FBI was watching him.

Attorneys for Bissey and William Vogel declined to comment. Attorneys for Betancur and Bonet did not respond to requests for comment.

1 phone, 12,000 pages of evidence

The documents highlight just how much digital evidence an ordinary person sheds in everyday life: In one case, prosecutors said they gathered more than 12,000 pages of data from a suspect’s phone using Cellebrite, a tool popular with law enforcement for its ability to penetrate locked phones and copy their contents. The search also recovered 2,600 pages of Facebook records and 800 cellphone photos and videos.

The FBI said it tracked down suspected rioters who had tried unsuccessfully to evade prosecution. In an affidavit supporting a search warrant application, an FBI agent said that a relative of Zachary Alam had told investigators he could be seen in video bashing some glass inside the Capitol with his helmet and that he was on the run with no intention of turning himself in. Agents got a D.C. judge to issue a “ping order” for his cellphone, which had been registered with T-Mobile under the name of Superman’s alter ego, Clark Kent, the affidavit said. That ping order allegedly pinpointed Alam’s location to Room 17 of the Penn Amish Motel in rural Pennsylvania. FBI agents arrested him there the next day.

Apple also gave investigators details of Alam’s iCloud account, including his home address, log-in information and the registration dates for his iPhone 7 and MacBook Air, the affidavit said. The tech giant was cited in several cases where agents seized suspects’ iPhones, but no document reviewed by The Post showed Apple providing detailed location data, as had Google and Facebook.

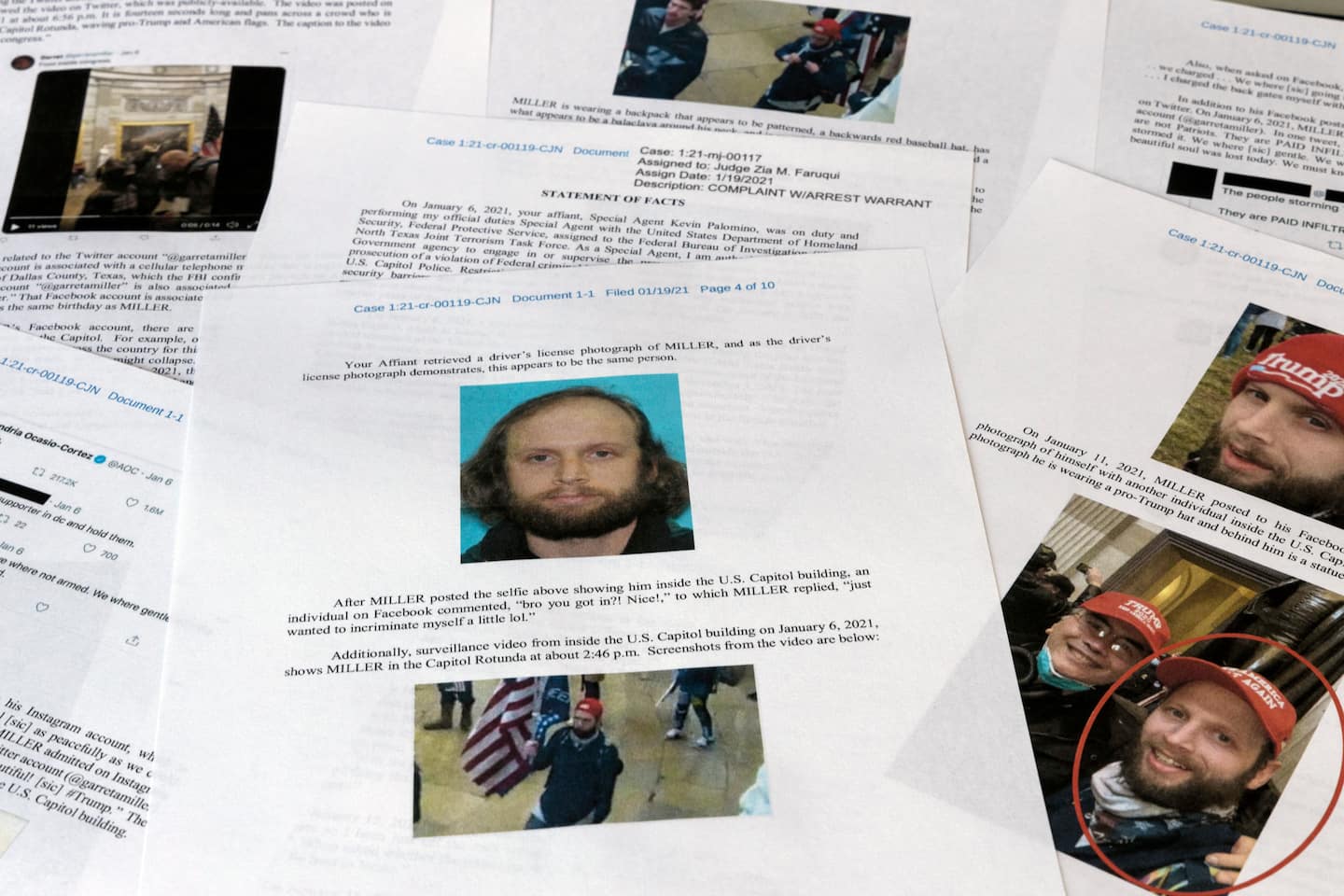

Others moved to cover their tracks far too late. After days of tweeting death threats to lawmakers and sharing Capitol selfies, saying he had “just wanted to incriminate myself a little lol,” Garret Miller (no known relation to Brandon Miller) had voiced a hint of caution by writing a Facebook post saying that “it might be time for me to … be hard to locate,” a criminal complaint states.

That same day, agents obtained a search warrant for his cellphone’s location data, which showed that his phone was inside his Dallas home. When agents arrested him there on Inauguration Day, Miller was wearing a shirt with Trump’s face on it that read, “I Was There, Washington D.C., January 6, 2021,” according to a filing by prosecutors last month opposing Miller’s release. Miller’s attorneys did not respond to requests for comment.

Another suspected rioter, Damon Beckley, told Louisville TV station WDRB that he deleted his Facebook account and removed his phone’s SIM card in hopes of evading the FBI. But agents said in a search warrant application that they were still able to match his face in cellphone videos and Capitol photos to his Kentucky driver’s license. (Federal investigators in Kentucky and other states are legally authorized to view state Department of Motor Vehicles records, no subpoena required.)

Investigators also filed a 33-page search warrant with Facebook demanding virtually everything Beckley had done on the site dating back to Nov. 1: all messages, draft messages, posts, comments, photos, videos, audio recordings, video calls, “pokes,” “likes,” “tags,” searches, location check-ins, privacy settings, session times and durations, calendar items, event postings (past and future), friend requests (approved and rejected), address books, friend lists and relationship status updates, as well as all dates, times, IP addresses, location information and other metadata linked to each item, plus any information he’d shared with the company, including his passwords, security questions, home address, phone number and any linked credit cards or bank accounts.

Beckley’s attorney declined to comment. In a Facebook post cited in the warrant, Beckley defended his presence inside the Capitol by writing that he had been “shoved in by Antifa.”

Outside facial recognition help

In a Facebook video captioned “Peacefully storming the Capital,” a man could be seen shouting, “In the Capitol baby, yeah!” as he joined a mob pushing past broken glass and into the building’s threshold, according to a criminal complaint. The FBI’s Operational Technology Division in Quantico, Va., ran that image through the bureau’s facial recognition search tool, which matched it to the California driver’s license photo of Mark Simon, whom agents called a “known activist” from Huntington Beach. He was arrested in California in January. His attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

Investigators went beyond official databases as well, the documents say. An amateur “sedition hunter” tweeted that the same man seemed to appear in two videos blasting a chemical spray at officers outside the Capitol and later talking about the clash while wearing camouflage pants and a “Guns Save Lives” sticker inside the lobby of an Arlington hotel, according to a criminal complaint.

Agents said they pulled the hotel’s booking reservations, then compared driver’s license photos to the alleged rioter on the video, whom they identified as a Texas man named Daniel Ray Caldwell. In a detention hearing after Caldwell’s arrest, the FBI agent testified that he also “used facial recognition technology to determine whether a picture of Defendant’s face matched with any video on the Internet,” and that the unidentified “software independently found a match” between Caldwell’s photo and the hotel video, according to a magistrate judge’s order last month.

The FBI declined to comment on its facial recognition techniques. Caldwell’s attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

Some cases hinged on facial recognition tips submitted to the FBI by outside agencies. After the FBI published “be on the lookout” bulletins with suspects’ photos, officials at the Harford County state’s attorney’s office in Maryland ran one of the images, of a man inside the Capitol with his mask sunk beneath his chin, through an unnamed piece of facial recognition software, according to a criminal complaint. The tool returned the face of Robert Reeder, smiling for a Maryland driver’s license photo in a gray hoodie like the one the suspect had worn on Jan. 6.

An FBI agent said in the complaint that Reeder cooperated several days later by handing over a mix of photos and videos from his phone showing himself and others surging through the Capitol. Reeder’s attorney declined to comment.

Increasingly pervasive use of facial recognition by local police forces also helped fuel the FBI’s nationwide manhunt. After the FBI began asking for help by circulating bulletins with suspects’ images, 12 detectives and crime analysts with the Miami Police Department began running the photos through Clearview AI, a facial recognition tool built on billions of social media and public images from around the Web.

Officers signed a contract with the tool’s creators last year, hoping for a potential breakthrough: Their other facial recognition search only looks through official photos, such as jail mug shots. But Clearview has faced lawsuits from advocacy groups arguing its technology violates privacy rights, and Google and Facebook have demanded the company stop copying their photos into its searchable database.

The Miami police team has run 129 facial recognition searches through Clearview and sent 13 possible matches to FBI agents for further investigation, said Armando R. Aguilar, assistant chief of the department’s Criminal Investigations Division, adding, “We were happy to help however we could.”

Clearview AI’s chief executive, Hoan Ton-That, declined to provide specifics but said in a statement to The Post that “it is gratifying that Clearview AI has been used to identify the Capitol rioters who attacked our great symbol of democracy.”

A passport application and a bank video

Unlike many of the Capitol insurrectionists, Philip Grillo had not immediately given himself away: He wore a mask, did not live-stream himself committing crimes, and stormed the Capitol shouting, “Fight for Trump” while holding a cellphone registered in his mother’s name.

But that did not stop the FBI, as agents alleged in a criminal complaint: After two tipsters called the bureau, saying they recognized Grillo on TV, agents trawling through Capitol surveillance camera footage spotted him leaping through a broken window and taking a selfie inside the Rotunda, his mask around his neck.

They compared his face on the video to a photo from Grillo’s application for a passport in 2017, the complaint shows, and they matched his embroidered Knights of Columbus jacket with one spotted in a YouTube clip of a violent brawl.

The agents said in the complaint that they also used a Verizon search warrant to determine that Grillo’s phone had been inside the Capitol, and they scanned license plate reader data from D.C. to New York, where he had been a Republican Party official in Queens: His Chevrolet Traverse had been spotted leaving New York City the night before and recorded near the Capitol at 2 a.m. the morning of the riot.

Later, photographers spotted Grillo leaving a federal court building in Brooklyn, using a hoodie to cover his face. His attorney declined to comment.

The FBI also has been aided by the online army of self-proclaimed “sedition hunters,” like the one who helped identify Caldwell. They scoured the Web for clues to track down rioters and often tweeted their findings publicly in what amounted to a crowdsourced investigation of the Capitol attack. The citizen sleuths organized their pursuits with hashtags: One man, Clayton Mullins, a Kentucky car dealer whose alleged assault of a police officer was captured on YouTube video, was given the viral hashtag “#slickback” for the way he wore his hair.

From that video, a tipster pointed the FBI to Mullins’s Kentucky driver’s license photo, which allowed FBI investigators to figure out where he had a bank account, according to a criminal complaint. In February, an agent talked to a bank employee, who not only told them Mullins had been there a day before but queued up surveillance video of him talking to a teller, wearing no mask and with his dark hair pushed back in that signature slick.

Mullins, whose attorney declined to comment, was released from federal custody last month on the condition that he not leave his home in western Kentucky, court filings show. His detention will be enforced by a location-tracking GPS monitor.

Spencer Hsu, Matt Kiefer and Julie Tate contributed to this report.