Abolishing the death penalty must be part of reimagining safety

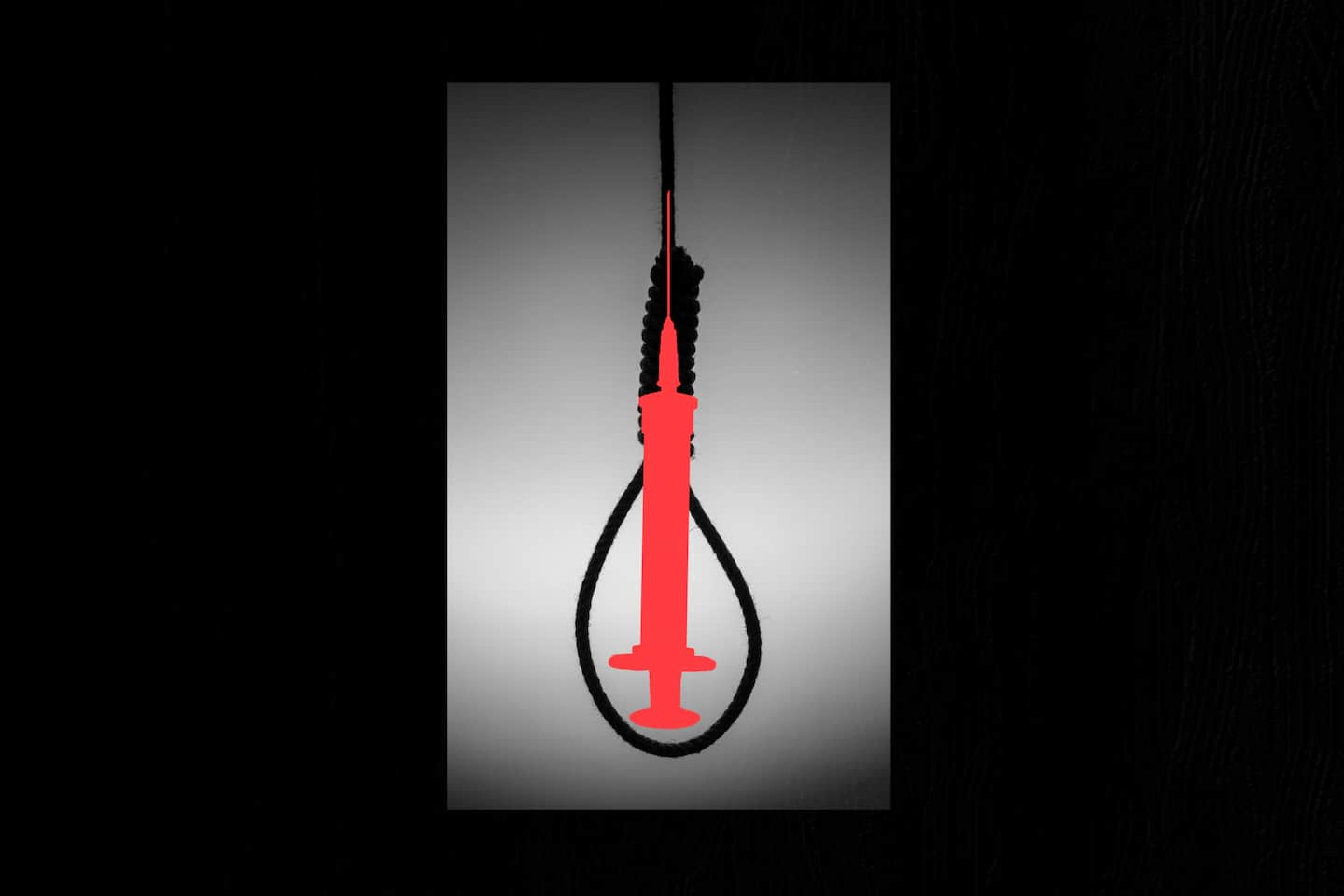

Through Charles J. Ogletree Jr. and Austin Sarat’s book “From the Lynch Mob to the Killing State” and the leadership of Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative, the white sheets that hid lynching’s horrors have been torn away. Stevenson has called capital punishment lynching’s “stepchild” and noted that “the states with the highest lynching rates are the states with the highest execution rates.”

Until recently, the death penalty has enjoyed broad public support in the United States, which has allowed public officials to quietly spend millions every year to kill a very select number of people. But the logic, values and trade-offs implicit in decisions to prosecute capital cases and pursue executions are being increasingly questioned by a public grown wise to the reality behind “tough on crime” rhetoric.

With the death penalty in retreat, and a national conversation unfolding over how overpoliced communities can better provide for their own safety, long-term abolitionists have the opportunity to do more than end an egregious and racist policy that has no place in a civilized country. They can align with those pushing for “community justice” — a future in which cities’ budgets and politics are truly responsive to the community’s evolving health and safety priorities, not stuck in the punishment-first approach of the past. Arising from “different centers of energy,” the movement to abolish the death penalty and the movement for community justice have the potential to create, in the words of Robert F. Kennedy, “a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

It has become increasingly difficult to argue that capital punishment has anything to do with either public safety or even punishment for individual wrongdoing. A decade of research laid bare claims that the death penalty is reserved for “the worst of the worst.” Rather, most death sentences are meted out to the poorest of the poor, the sickest of the sick, the blackest of the Black, and to those with long histories of abuse, trauma and mental illness and who are represented by incompetent, overworked and under-resourced counsel. We now know that fewer than 16 counties — or roughly one half of 1 percent — return five or more death sentences per year. These “death penalty counties” share at least three systemic deficiencies: a history of overzealous prosecutions, inadequate defense lawyering, and a pattern of racial bias and exclusion throughout the justice system.

How do we best allocate resources to truly keep everyone as healthy and safe as possible? When viewed from this perspective, an alliance between activists of color advancing community justice and death penalty abolitionists — whose ranks are often whiter — becomes almost inevitable. Capital punishment is more than a visceral and tragic indication of which lives matter in our society. It vividly and powerfully illustrates how scarce public resources and attention are misdirected to support “the machinery of death” instead of policies that will actually promote well-being.

Similar currents flow through neighborhoods organizing for community justice. Families for Justice as Healing surveyed the highest incarceration communities in Boston. The resulting People’s Budget differed significantly from the official one unveiled by the mayor. It prioritized safe and affordable housing, healing and treatment centers, community-led violence and gun-prevention programs, public education, parks, community centers and city infrastructure. That same gap is prominent in the movement to transform the criminal legal system. A nationwide survey by the Alliance for Safety and Justice of more than 800 victims of crime found that 60 percent “would prefer a system that dealt shorter prison sentences and invested more resources in prevention and rehabilitation programs,” as the Urban Institute said. “This is true even among survivors of serious violent crime.”

After laying the groundwork to dismantle segregated schools, Charles Hamilton Houston, known as the lawyer who killed Jim Crow, recognized that other challenges remained. He insisted that “all of our struggles must tie in together and support one another.”

Today, we are poised to heed Houston’s insight. Death penalty abolitionists can join proponents of community justice in mobilizing White allies to advance what Patrisse Cullors, co-founder of Black Lives Matter, has called an “an economy of care,” in which investments in housing, education, jobs, violence prevention, health care and civic engagement take priority over policing, prisons and prosecutions. Such a potent alliance has the opportunity to propel policymakers to think beyond tinkering with an inhumane social order. By advancing a genuine redesign of public policy and resource allocation, they can ensure that “We the People” includes all of us.

Read more: