Humans solve problems by adding complexity, even when it’s against our best interests

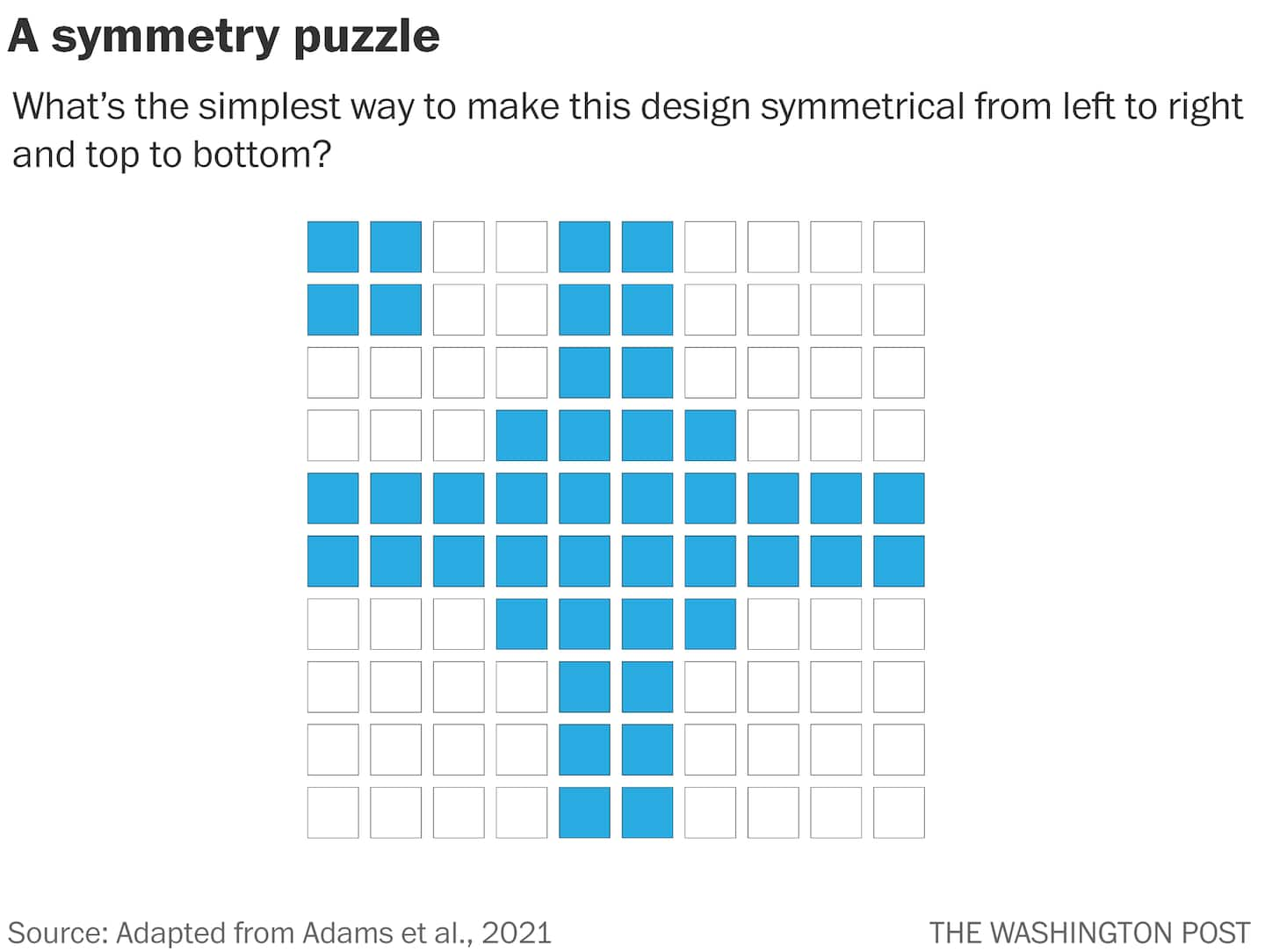

The simplest solution — and the correct one — is to change four squares in the upper-left quadrant from blue to white. But when a team of researchers posed this problem to hundreds of volunteers in a controlled experiment, fully half of them failed to do so.

Instead, they opted to color the remaining three quadrants to match the upper left one. They added complexity to the design instead of taking it away, even though doing so required more work and hurt their performance, according to the problem guidelines.

The researchers say this experiment, and a number of others they published in a recent paper in the journal Nature, reveal something fundamental about the human psyche: We tend to solve problems by adding things together rather than taking things away, even when doing so goes against our best interests.

It’s a tendency that may have especially wide-reaching implications for the realm of public policy.

“The tendency to overlook subtraction may be implicated in a variety of costly modern trends, including overburdened minds and schedules, increasing red tape in institutions and humanity’s encroachment on the safe operating conditions for life on Earth,” the authors write.

The grid problem was one of eight experiments reported in the paper. In another, subjects were asked to stabilize the wobbly roof of a Lego structure by either adding or removing bricks. The easiest solution was to remove a single brick, allowing the roof to lie flat atop the base. But only 40 percent of participants took this route; the others added bricks to create more supports, even when doing so reduced the amount of money they received for completing the task.

When subjects were explicitly told that removing bricks was free and had no effect on their pay, the share opting for the subtractive solution rose to only 60 percent. Similar patterns turned up across a variety of experiments, including edits to a written document, modifications to a mini-golf course, and suggestions for improving a university.

There are a variety of explanations for why we might favor addition over subtraction in problem solving, the authors write. “Numerical concepts of ‘more’ and ‘higher’ may map to evaluative concepts of ‘positive’ and ‘better,’” for instance. In many fields it may be easier to gain recognition for creating something than for taking something away.

This could be especially true in politics. Donald Moynihan, a professor at Georgetown’s McCourt School of Public Policy who was not involved in the research, noted via email that “lots of our biggest policies suffer from creeping complexity.”

Moynihan studies administrative burdens — “the frictions that people encounter in their experiences with government,” such as long lines at the DMV or convoluted application forms for federal programs. He says that the additive tendencies identified in the Nature paper may be driving some of that.

“There is a well-established bias toward building on the existing base in public policy,” he said via email. Part of this is simple conflict avoidance: eliminating policies often requires butting heads with the people those policies benefit, which can quickly derail a legislative initiative.

Leidy Klotz, one of the researchers on the project and author of the just-published book “Subtract: The Untapped Science of Less,” notes that the Code of Federal Regulations — the record of all rules and regulations by federal governmental agencies — has ballooned from 10,000 pages during the Truman era to more than 180,000 today.

Factoids like this often form the basis of conservative and libertarian arguments about government waste or overreach.

“The buildup of regulations over time leads to duplicative, obsolete, conflicting, and even contradictory rules, and the multiplicity of regulatory constraints complicates and distorts the decision-making processes of firms operating in the economy,” as a 2016 Mercatus Center study put it.

Moynihan, however, takes a slightly different view. “I would like policymakers to relentlessly look at existing processes to see if there are simpler (from the perspective of the public) options to achieve the same goals,” he said. “In some cases, that means, contrary to a libertarian perspective, investing more in government capacity.”

Moynihan points to the Social Security retirement program as an example of “a big and complex program, but one that is designed to feel simple for retirees.”

The authors of the Nature study stress that their findings don’t imply that adding things is always a net loss from a policy perspective. “Our conclusion is that people systematically overlook subtraction; it’s not that subtraction is always better,” Klotz said. “Adding and subtracting are complementary ways to try to improve things. So as applied to the lawmaking realm, we just want to be sure people are considering all of the options.”