Design with a social mission

Sasha Plotitsa wasn’t one of those business titans who started the perfect job right out of college and climbed steadily up the corporate ladder. He worked in construction, ran a cannabis dispensary, invented a meal tote for weightlifters, created Braille signs and styled interiors. He also found time to volunteer and made sure he followed green building practices. Now, at age 50, he’s taken bits of every job, skill and passion and baked them into Formr, a small San Francisco furniture company where the materials and makers have a compelling backstory.

The name of the one-year-old company starts with the word “form” and relates to the formerly incarcerated individuals hired to produce the pieces from formerly used (repurposed) wood. The minimalist, playful lap desks, candleholders, floating end tables and wine racks (there are 12 designs) come in quirky colors such as pink, chartreuse or mint and have offbeat names like the “HANGover” coat rack and the “SHELFish” shelf. Priced from $89 to $619, they are handmade in a onetime car repair shop in San Francisco’s Hayes Valley, a once gritty area that has become a hip neighborhood in the heart of the city.

Plotitsa’s earlier pursuits focused on being successful financially and making a profit. But he’s always found time to give back to causes he believed in. A few years ago, he decided to make a change and direct more of his attention on that kind of work. “Maybe it’s my midlife crisis or whatever you want to call it, but I wanted to find a way to do something that I am passionate about, and that is designing, and combine it with a social mission. I wanted to provide opportunities for people coming out of prison and starting a new life,” he says.

[Changing spaces: How Black designers are combating inequity in an overwhelmingly White industry]

His little company is getting noticed. In June, West Elm added Formr to its Local online program, which showcases handcrafted and artisan-made products from 150 small businesses, bringing the designs of underserved communities to a national audience. “We loved Sasha’s business sense and his storytelling,” says Larysa Polansky-Hayes, head of the West Elm program. “The way he takes these different components and puts them together in a witty and clever way, he is onto something.”

Sasha Plotitsa, founder of Formr.

Sasha Plotitsa, founder of Formr. Plotitsa’s personal story starts in Ukraine. He was 7 years old when he left Odessa with his parents and came to America, where the family eventually settled in San Francisco. His parents were both creative: His mom was an artist and played the piano, and his dad became a contractor. As a child, Sasha loved to draw and wanted to pursue art in some form in college. He says he also has always been “a curious person who enjoys experimenting.” He expressed an interest in architecture but ended up studying industrial design at San Jose State.

After college, he joined an acquaintance on a venture to import night-vision binoculars from Russia. Plotitsa did all the graphics, advertising and packaging for the project. “I was the entire art department. I learned a lot,” he says. He spent some time in the sign business and at his father’s construction company, helping with interiors, specifying tile and finishes, and sourcing green building materials. At work sites, he says, he was “blown away” by all the wood scraps and other waste material that ended up at the dump.

From 2008 to 2018, he worked in the cannabis dispensary business. Plotitsa made sure his dispensary stood out from the pack. “Most dispensaries looked bad. They were furnished with a horrible shag rug, a Bob Marley poster and a beat-up couch,” he says. Plotitsa created one with a spalike setting. Eventually the dispensary was closed down by the federal government, but while he was running it he encountered many people who had been imprisoned after being caught with marijuana.

“The experience opened my eyes to the fact that this was happening across the country and people were coming out of prison with a record and starting their lives over with many barriers and obstacles which made it difficult to find a job,” Plotitsa says. “It opened my eyes to the concept that people like this needed a fresh start.”

The issue resonated with Plotitsa, who had always made volunteering a priority, whether it was helping Russian immigrants improve their English or serving meals to the homeless and AIDS patients. Helping others was something of a family tradition. His parents often sponsored families from Odessa looking for a new life, and his dad gave jobs to family members and friends.

In 2018 Plotitsa was ready for his next adventure. He wanted to design furniture, but he wanted to produce it in a socially conscious way. He had already sketched out a plan to retrieve salvage materials from contractors. But that didn’t feel like enough. He searched Google for something to spark his imagination. His thoughts drifted back to his past in the cannabis world and the challenges facing people who had been incarcerated. When he realized that prisoners often had access to woodworking programs, his idea took shape.

After more than two years of planning, designing and prototyping, Formr was ready to begin hiring.

Cris Wolf, left, works on a lap desk with Plotitsa.

Cris Wolf, left, works on a lap desk with Plotitsa. Finding former prisoners who had carpentry skills proved challenging. Plotitsa researched about 50 organizations that worked on reentry of formerly incarcerated individuals. These people’s lives were often complicated. But the reason for their incarceration was not something he considered when hiring. “It is not my place to judge their past and what they have been incarcerated for and decisions they have made,” he says. “They have served their time based on their sentence, and they are looking to start their lives over. I want to be able to help them.”

A small core of workers has been nurtured to handle the job and the responsibilities. Cris Wolf is one of Plotitsa’s three part-time employees at present. Wolf, 46, moved around a lot when he was a child. But one thing that stayed with him was the time he spent with his grandfather in Vallejo, Calif. “My grandfather did a lot of work with his hands. He was Osage so he taught me about working with natural materials. That is where I fell in love with that,” he says. Wolf graduated from high school and served in the Army, but he had a history of trauma and mental illness and made some bad choices. He was incarcerated for 19 years, he says, “for taking someone’s life.”

“I was released on a conditional program which helps me with monitoring my mental illness and just kind of making sure I am staying in therapy and keeping myself safe,” Wolf says. He saw a posting on a jobs website for a woodworker and noted that the company hired people who had been incarcerated. “If anyone will give me a shot, then it’s this guy,” he says. “So I applied and it ended up working out.”

Wolf says sometimes he gets tired, and he feels pressure to get things done. “But most of the time it’s really satisfying work, and I love going home and feeling like I’ve accomplished something and made something beautiful,” he says.

The idea of recycling construction debris also proved a bit more challenging than Plotitsa had anticipated. Some businesses were hesitant to add another step in their construction workflow. One person who did sign up was Dmitry Shapiro, who had met Plotitsa through their kids. Shapiro, 47, is a project manager at CB Construction, a company that focuses on upscale residential projects in San Francisco.

“It hurts to have all this wonderful wood that’s been around for 100 years thrown away,” Shapiro says. Plotitsa often scores old redwood beams and other materials from Shapiro’s remodeling projects, then his employees remove the nails and screws from the wood and clean it up.

Quincy Lewis paints a lap desk.

Quincy Lewis paints a lap desk. Shapiro says that although he thought his friend’s business proposition was cool, he was at first skeptical of his plan to use formerly incarcerated workers. “It felt a bit risky to me,” he says. “But he has found some pretty stellar dudes, so he seems to make it work.” (Plotitsa’s first employee was actually a woman.)

Plotitsa knew the furniture itself would have to be functional and funky to catch the eye of shoppers. He focuses on smaller pieces that make life at home more comfortable, organized and joyful. “Cool,” for example, is a shelf that holds and displays sunglasses near a front door. The “UnderSTUDY” wall-mounted desk holds a computer and is small enough to create a workspace in tight quarters. The “overLap” has room for a laptop and coffee and features a groove for a phone. When it’s not a desk, it can be a side table.

He set a launch date of March 11, 2020, an inauspicious choice, as the world started shutting down because of the coronavirus. But he had at least two good things going for him: He was making small-scale furniture suitable for people working at home, and it was sold online.

The first three months looked bleak. In less than a week, there was a shelter-in-place order. He had to furlough his one employee. “Within a week of opening, I thought of closing,” he says. With the support and encouragement of his family, though, he forged ahead. After some starts and stops, he reopened June 17, 2020, and has operated continuously since then.

Plotitsa and his wife, a therapist, have two kids. “I’m fortunate that my wife is the main breadwinner right now and I have her support,” he says. “It’s not been easy during covid. It’s not cheap to sustain a business and pay people a fair wage in San Francisco.”

“Lots of customers have been excited about the mission and have bought furniture because they feel positive about making that purchase,” he adds. “It’s just as much a priority as the design itself.”

His wish list for the future includes retail locations, adding technology to allow for recycling other types of building materials, and franchising the business model.

The most challenging part of his job, he says, is finding and retaining employees. “It’s difficult to be levelheaded at times, like when an employee doesn’t show up and there are orders to fill,” Plotitsa says. “Then the next day you get a call from West Elm. It’s tumultuous, but it’s also exhilarating and exciting.” Building rapport with his employees beyond just being a boss is something he strives for each day. “I want to support them in their lives,” he says.

He has made adjustments to his style of working with Wolf and other employees, who often have many insecurities. “I try to prop them up and support them and be optimistic and positive about the work they are doing,” Plotitsa says. “I’m not the best communicator, but I’ve learned to be better. I am learning things from Cris, too, and he is trying to communicate with me about the concerns that pop up for him.”

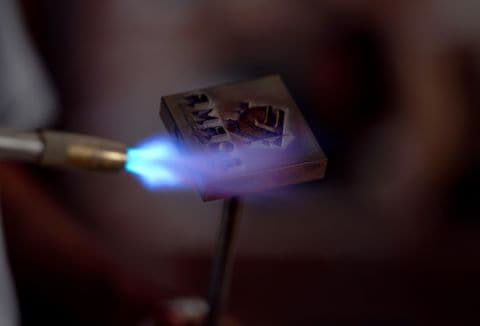

Luis-Miguel Bermudez heats a stamp to brand furniture.

Luis-Miguel Bermudez heats a stamp to brand furniture. Jura Koncius covers interiors and lifestyle for The Post.