If there’s one thing Justice Samuel Alito got right in his draft opinion striking down Roe v. Wade, it’s that Roe and later cases upholding it never had the desired effect of settling the issue politically.

The near extinction of the congressional middle on abortion

The justices added: “It is the dimension present whenever the Court’s interpretation of the Constitution calls the contending sides of a national controversy to end their national division by accepting a common mandate rooted in the Constitution.”

Just a year later, however, soon-to-be Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg would reflect that Roe had, in fact, “prolonged divisiveness and deferred stable settlement of the issue,” by virtue of how it had been decided.

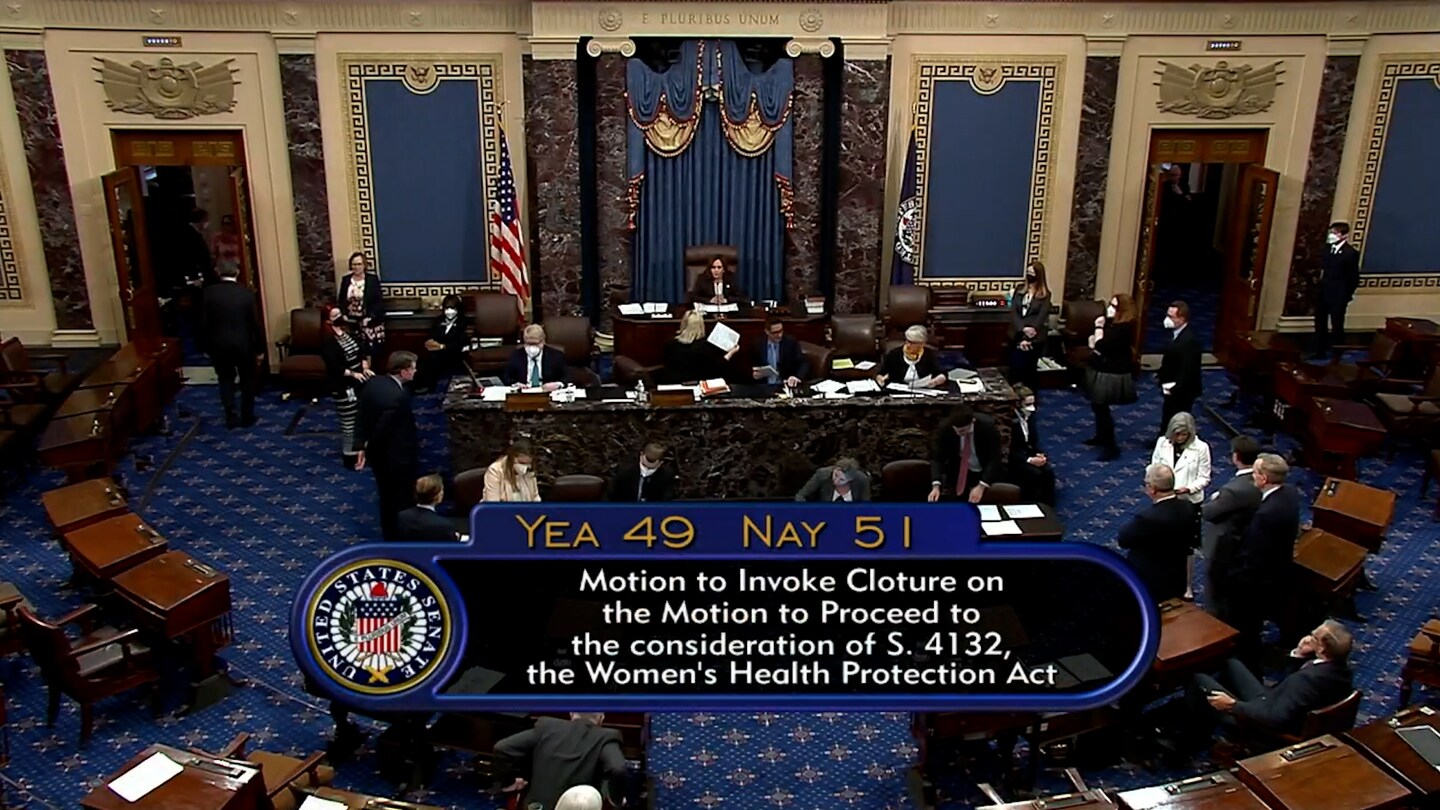

Today, the apparent imminent overturning of Roe has produced a stark indicator of just how irretrievably polarized this issue has become. The Senate on Wednesday voted almost exclusively along party lines to halt a bill that would codify abortion rights into federal law. The two GOP senators who have said they support abortion rights, Sens. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Susan Collins (R-Maine), both voted against it. Just one senator crossed party lines — Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) — even as he supported the failed bill’s stated aim of codifying Roe.

And among the Democrats who did support the bill was Sen. Robert P. Casey Jr. (Pa.), who first ran for his job in 2006 by emphasizing his “pro-life” views — and even indicated he supported overturning Roe. Casey also happens to be the son of the “Casey” from the Casey case, the former Pennsylvania governor of the same name who challenged Roe in the nation’s highest court.

One conservative commentator called the younger Casey’s vote, “The end of pro-life Democrats.”

That might be overstating it slightly: Manchin still calls himself “pro-life” — even as he says he would vote to codify the protections laid out in Roe, as long as states could keep some of their restrictions in place. And there remain outliers among both federal and state officials.

But the trend in congressional votes on abortion over time is clear and unambiguous. And the growing (and now almost complete) partisan chasm we see today traces back to when Roe was decided in 1973.

In a 1997 study, Carnegie Mellon University professor Greg D. Adams sought to track abortion votes in Congress over time. His finding: In the Senate, there was almost no daylight between the two parties in 1973, with both parties voting for “pro-choice” positions about 40 percent of the time.

But that quickly changed.

There was more of a difference in the House in 1973, with Republicans significantly more opposed to abortion rights than both House Democrats and senators of both parties. But there, too, the gap soon widened.

Including votes in both chambers, Adams found that a 22 percentage- point gap between the two parties’ votes in 1973 expanded to nearly 65 points two decades later, after Casey was decided.

“Democrats and Republicans were only moderately divided over abortion during the 1970s but became extremely polarized by the latter half of the 1980s,” Adams wrote. “By the end of the series, over 80% of Democrats were voting pro-choice on abortion disputes, while the same percentage of Republicans were voting pro-life.”

Today, the yawning gap has become almost complete. On a bill presenting the most basic of abortion rights issues — whether such a right should be in federal law — there was only one crossover vote out of 100 in the Senate, and one out of 429 in the House when that chamber passed the bill last year. In each case only a single member — a Democrat — crossed over.

(It’s also worth noting that the likes of both crossover votes may soon disappear. Manchin comes from a deep-red state and has been targeted for a party switch, while Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Tex.) is being targeted in a primary in large part due to his abortion stance.)

It is, of course, entirely possible we’d be seeing this level of polarization on abortion even without Roe. So many other issues that didn’t divide Congress so neatly once upon a time now do so with regularity. But it’s notable that the likely end of Roe, 50 years after the decision, has apparently ushered in an almost complete partisan split.

That doesn’t mean we’ve seen the absolute end of moderates or officials who cross party lines on this issue. In New Hampshire, Republican Gov. Chris Sununu is promising that abortion will remain “safe and legal,” even as Republicans control the legislature and could severely restrict or even ban abortion. Vermont Gov. Phil Scott (R) has signed a major expansion of abortion rights in his state. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan (R) has said he personally opposes abortion but that he would not try to change Maryland’s laws. Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) opposes abortion rights but also says he opposes the state GOP’s severely restrictive bill, which would charge abortion as a homicide and punish both the provider and patient accordingly.

In Congress, though, the pressure to toe the line on specific votes has proven increasingly compelling — as evidenced by the likes of Casey, Manchin, Murkowski and Collins. They’ve seen their ranks diminish over the years, via both primaries and attrition.

And now that everyone will soon have to navigate a world in which lawmakers actually get to decide all of these issues, the partisan divide is likely to get even more dug-in.