KETA, Ghana — Bwap, bwap, bwap. Bellah Ibrahim, my tour guide for the day, was trying to whack the broken sides of a wooden table together with his hands. It wasn’t working.

This crumbling African slave fort should be preserved to honor the enslaved

I was looking at centuries-old chairs that were used by the slave overseers and perusing illustrations of enslaved Africans being chained, inspected and sold by their European masters. Bwap bwap, bwap. I turned to add my two cents’ worth of construction advice. “You’ll probably need to get some nails.”

“You are right,” Bellah said. “Come, we will finish the tour, and I’ll find some.”

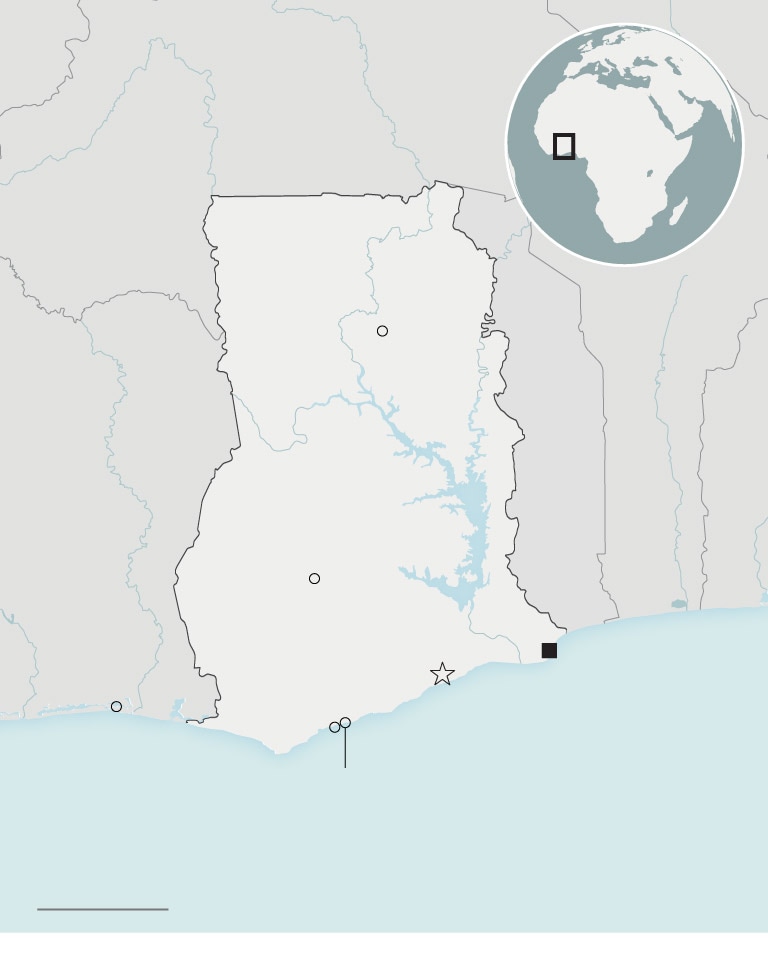

Classified as a UNESCO World Heritage site, Fort Prinzenstein is much smaller and less famous than the slave forts at Elmina and Cape Coast, some 200 miles west, and it attracts far fewer tourists — in fact, I was the only visitor that afternoon. Unfortunately, as rising seas relentlessly erode the site, I may be among the last.

Follow Karen Attiah‘s opinions

FollowBellah, who walks with a limp, showed me the dungeons for captured women. He pointed out the remains of a holding cell that couldn’t have been bigger than 10 by 15 feet. “They would put 50 to 100 women in there,” he said. “And they were forced to eat in there, too.” Nearby was a line of shallow tubs filled with rainwater. The women had to use the water both to bathe and drink.

We entered an enclosed area with a black-painted gate in the wall that faced the sea. A typewritten sign identified it as “The Gate of No Return.” On the ground lay what looked like a an old link from a heavy chain. Bellah told me that when the overseers felt that captives were making trouble, they would chain them lying face-up on the ground, to expose their eyes to the burning sun.

To the left of the Gate of No Return was the holding cell for captives about to be put on slave ships for the treacherous voyage to the Americas. Words painted on one wall read in part, “Welcome For Spiritual Reconnection With Ancestors Who Were Brutally Uprooted From Their Natural Abode.” Bellah said people believe the ancestors’ connection is fused into the very stones: Splotches of green coloration are where there were bloodstains. Bits of skin and fingernails are embedded where desperate people tried to claw their way out. The bones of those who died before they were shipped out were ground up to build parts of the wall. It was hard to not be overtaken by the gruesomeness of it all.

BURKINA FASO

IVORY

COAST

Cape Coast

Gulf of Guinea

THE WASHINGTON POST

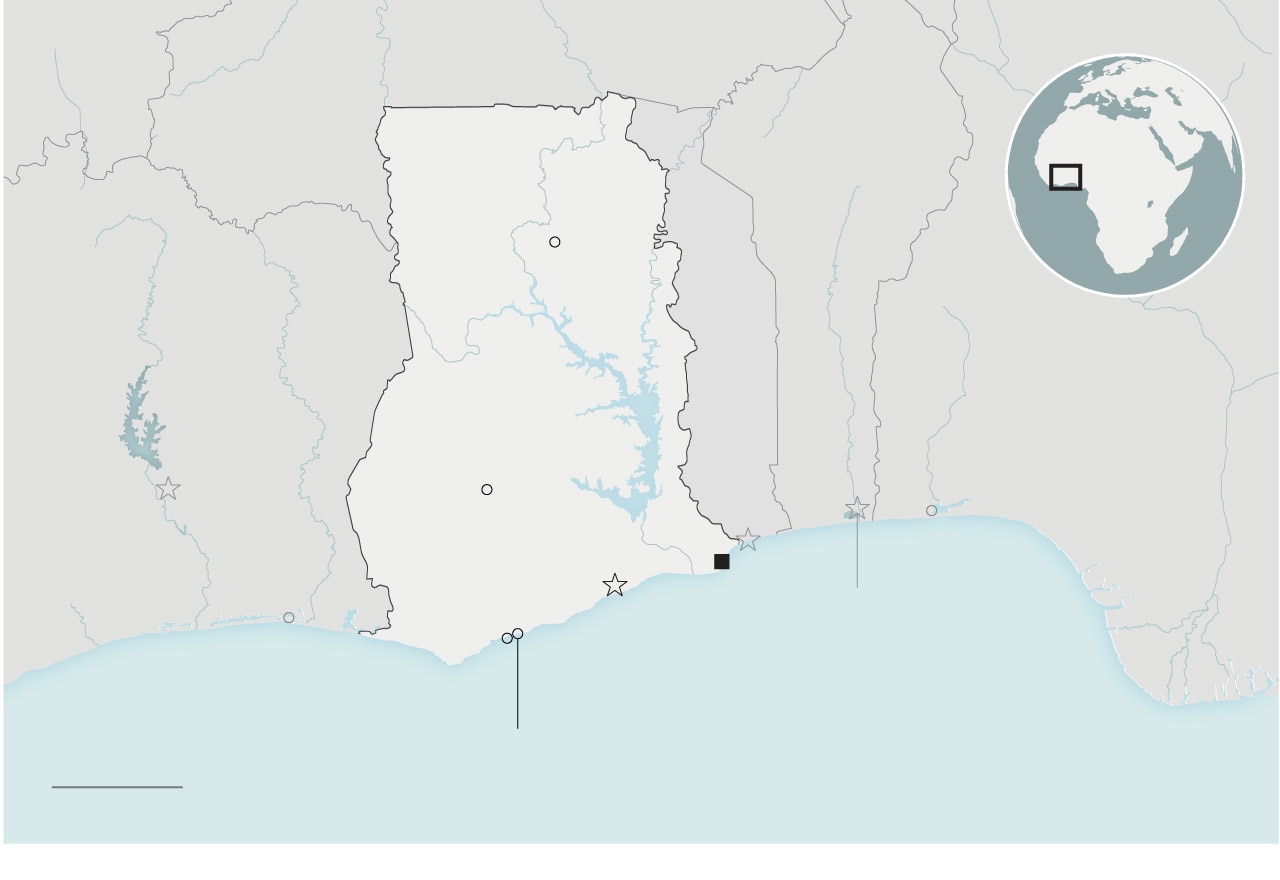

BURKINA FASO

IVORY

COAST

Cape Coast

Gulf of Guinea

THE WASHINGTON POST

BURKINA FASO

IVORY COAST

Yamoussoukro

Porto-Novo

Cape Coast

Gulf of Guinea

THE WASHINGTON POST

“But, you know, people come here for healing,” Bellah said. He pointed to empty bottles on the floor: They had held libations offered by modern Africans to the souls who had suffered in that space, and he has heard some say a visit cured their illnesses. Outside the fort, Bellah plucked some herbs growing among the ruins, known locally as ebomah. “This is good to take to improve fertility,” he said, smiling. “Especially for men.”

Maybe the stories about the bloodstains and healing and herbs are true, and maybe they aren’t; the Ewe people of this region are known — even feared — for their intense spiritual practices. But it almost doesn’t matter. Bellah, who has been a tour guide for 10 years, told me he’d spent a good amount of that time collecting the stories of local elders from the area. Hoping to bring visitors to Fort Prinzenstein, he’s doing his best to construct compelling narratives — narratives showing that life and healing can exist on the site of death and suffering. That beyond their value as a historical site, the ruins have a sacredness, a spirituality. That we have a duty to honor the Africans who suffered or died within these walls.

This is why the fort’s pending demise is so unfortunate. The sea had already claimed a large portion of the site by 1980, and from what I could find, there has been a lot of discussion since then but no large-scale action to preserve what remains. Like so many other historical markers of Black burial and death, in both Africa and the Americas, Fort Prinzenstein is at risk of being lost — in this case, within a few decades.

Bellah left me to walk around the ruins alone. Clink clink clink — I could hear him back at work on the broken desk, using a rock and some scavenged nails to hammer it back together. Another day, another small attempt to save a piece of painful history — to stave off destruction in the name of those whose lives were destroyed.