“He stood on pinnacles that dissolved into precipice,” Henry Kissinger said of Richard M. Nixon at the former president’s funeral in 1994. The dark, purpled sky on that stormy day in Yorba Linda, Calif., made all the eulogies more memorable, but it was Kissinger’s line that remains embedded in my mind.

Robert McFarlane had his fall, but it’s the pinnacles that mattered

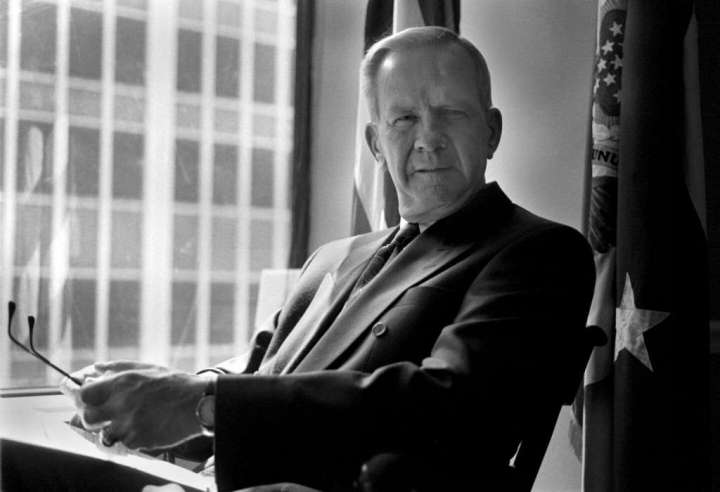

It came again to the fore when news of the death this month of retired Marine Lt. Col. Robert McFarlane, national security adviser to President Ronald Reagan, National Security Council staff member under Presidents Nixon and Gerald Ford, aide to Kissinger, White House fellow, decorated Marine combat veteran of two tours in Vietnam, Annapolis graduate, husband, father, patriot. He was 84.

He told me to call him “Bud,” as everyone did when we first met after I sat in on one of his regular graduate student seminars at the Nixon Library — one devoted to the terrible decisions that drove early, and eventually massive, intervention into Vietnam’s war with itself. As a civilian son-in-law of a Marine Corps colonel, I, of course, always called McFarlane “colonel,” but in these past few years when we met, he was the most gracious of men with his time and expertise. His last years were spent pressing everyone who would listen on the need to compete with the Chinese Communist Party in providing small, reliable and safe nuclear power plants to the developing world in order to combat carbon emissions, assist in global development and counter the grand strategy of Chinese President Xi Jinping. McFarlane had made himself master of this field, as he was of almost everything he ever put his mind to.

Our tenures in the Reagan White House overlapped, but of course, the national security adviser dealt with White House counsel Fred Fielding and deputy counsel Dick Hauser, not the junior briefcase carrier in the then-nine-lawyer office. Later in life, though, I treasured those conversations as colleagues in a common endeavor — conversations because of his character, not his résumé or influence.

Like Nixon, McFarlane achieved “the pinnacle,” for national security adviser is one of the three jobs in any White House — along with chief of staff and counsel — where the holder sees and weighs it all as he advises the most powerful executive in the world. And as with Nixon, McFarlane’s fall, as the Iran-contra scandal came to unfold around him, was far and hard, so hard, in fact, that in 1987 he tried to take his own life. As “one of the capital’s most self-contained of public and powerful men,” the New York Times’s obituary read, McFarlane told the paper that he believed at the time of his suicide attempt it was “the honorable thing to do.”

It wasn’t, of course, as this most permanent of “solutions” to any temporary problem never is, but people of real and deep honor feel all disgrace so deeply, or used to, that the attempt did not shock many of his friends for long. One of those friends, Nixon, appeared unexpectedly in McFarlane’s hospital room, to tell his former aide that he could never give up, that the attempt was merely a setback, that he needed to keep fighting for the causes he believed in.

Which McFarlane proceeded to do for another 35 years. The ground re-formed under McFarlane’s precipice. His longtime friend Jim Cicconi, who was an aide to James Baker in the Reagan White House, related to me how generous McFarlane was in time and guidance to younger staff, how he was unfailingly positive (and how he could do an impersonation of Kissinger that left everyone smiling). Having worked for Nixon and Kissinger, and then Ford and Reagan, advising as one of Washington’s wise old hands became his quiet and influential role. But his time with the grad students discussing platoon-level experiences in Vietnam layered into grand strategy — that is what I recall best. So many pinnacles in one life.

Many of the best and the brightest will fall and hit a bottom, will make not just a mistake but a terrible error of commission or omission. Most will not receive the public pardon that President George H.W. Bush gave to McFarlane. But all can do what McFarlane did: Turn a personal disaster into the floor from which the first step up, almost always via service to others, is made.

McFarlane was quiet and courageous; humble and very, very smart; slow to anger (if he ever got there) and quick to respond to requests for help. For every young striver inside the Beltway, his life — long and well-lived — is worthy of study and reflection.