“The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience,” Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. observed more than a century ago. The current Supreme Court, with its six-justice conservative majority, disagrees. Its ruling dramatically expanding gun rights spurns both logic and experience for the phony comfort of history.

Flawed reasoning in gun ruling shows how Breyer will be missed

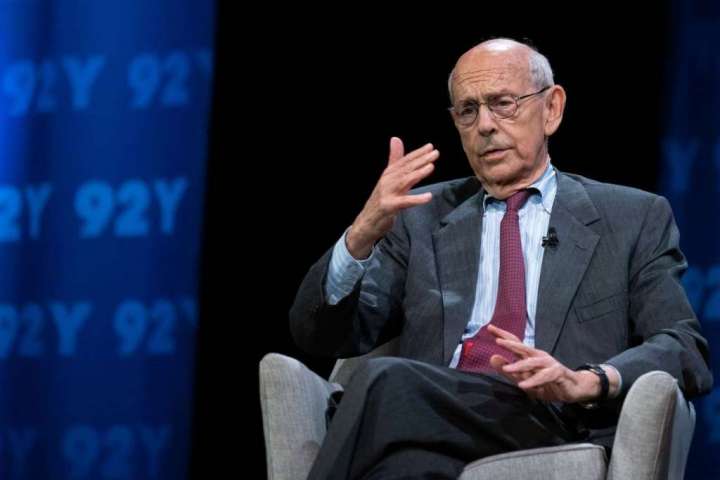

The conservative justices may have convinced themselves that looking at gun rights through the lens of history — whether the gun regulation at issue is consistent with the kind of restrictions that were in place when the Constitution was written or amended — prevents courts from substituting their own policy preferences for clear constitutional commands. This is self-serving rubbish, as Justice Stephen G. Breyer demonstrates in his dissenting opinion, albeit in more polite terms.

The dissent, joined by liberal justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, will be one of Breyer’s last, with just seven cases remaining to be decided this term. It offers not only an opportunity to reflect on how badly the majority has erred in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, but how much Breyer, with his insistence on bringing a common-sense approach to the art of judging, will be missed.

The majority’s initial error is upending the approach taken by every federal appeals court to consider the issue since the court established an individual right to bear arms in 2008’s District of Columbia v. Heller. Those courts have set out a two-part test. The first is historical: Is the limitation on guns at issue similar to what has been regulated in the past? If so, no Second Amendment problem. If not, the second test comes into play: Is the regulation justified by an important governmental interest?

Follow Ruth Marcus‘s opinions

FollowWith the New York ruling, the court reduced judges’ role to a single task: determining whether “the regulation is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.”

But as Breyer persuasively argues, the history of gun regulation is conflicting, elusive and fundamentally inadequate to the task of judging the legality of present-day rules. “How can we expect laws and cases that are over a century old to dictate the legality of regulations targeting ‘ghost guns’ constructed with the aid of a three-dimensional printer?” Breyer asks. “Or modern laws requiring all gun shops to offer smart guns, which can only be fired by authorized users? Or laws imposing additional criminal penalties for the use of bullets capable of piercing body armor?”

As he notes, “Laws addressing repeating crossbows, launcegays, dirks, dagges, skeines, stilladers, and other ancient weapons will be of little help to courts confronting modern problems.”

Judges can’t robotically reason by historical analogy to determine the legitimacy of modern gun regulation. To pretend they can does a disservice to democratic values and the changing needs of a society. It substitutes the illusion of impartiality for the hard task of judging.

And, make no mistake, the impartiality is an illusion. History is malleable — the New York case itself offers a master course in cherry-picking examples. But over time, the insistence on hunting down precise historical counterparts or coming up with plausible historical analogies tends to work against upholding gun restrictions.

Breyer poses this in question form — “will the Court’s approach permit judges to reach the outcomes they prefer and then cloak those outcomes in the language of history?” — but the answer seems pretty obvious, certainly in the hands of judges inclined toward a broad understanding of Second Amendment protections. Conservatives have rigged the system against gun regulation.

Breyer’s dissent offers a better way — and it is vintage Breyer, anchored in real-world concerns and presenting pragmatic solutions.

You would not know, from reading Justice Clarence Thomas’s majority opinion, that the nation was mired in an epidemic of gun violence or traumatized by mass shootings of schoolchildren and grocery-shoppers. Breyer leads with that — “In 2020, 45,222 Americans were killed by firearms,” his opening sentence reads — and keeps going, for several gruesome pages of statistics on gun violence.

This recitation did not sit well with Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., who wrote a separate, rather ill-tempered concurrence devoted entirely to rebutting Breyer’s dissent. “It is hard to see what legitimate purpose can possibly be served by most of the dissent’s lengthy introductory section,” he writes.

Is it? For Breyer, judges do not operate solely in the arid realm of text and history, but in the arena of practical consequences, for public safety but also for democratic values. Answering Alito directly, he says his goal was to demonstrate that the “question of firearm regulation presents a complex problem—one that should be solved by legislatures rather than courts.”

He continues to write, “The primary difference between the Court’s view and mine is that I believe the [Second] Amendment allows States to take account of the serious problems posed by gun violence that I have just described.”

Logic and experience, under the majority’s view, yield to what Breyer described as a “rigid history-only approach.” For Breyer, the law is a flexible instrument, one that should be used to optimize democratic governance. His Bruen dissent will stand as a rebuke to the majority’s cramped view, and a reminder of what the court will lose with his retirement.