Bored working as a computer engineer at IBM in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., Larry Josephson began volunteering in the mid-1960s at WBAI, a ragtag listener-supported FM station in New York City where he was assigned to host the morning show because, he said, no one else at the station was willing to wake up that early.

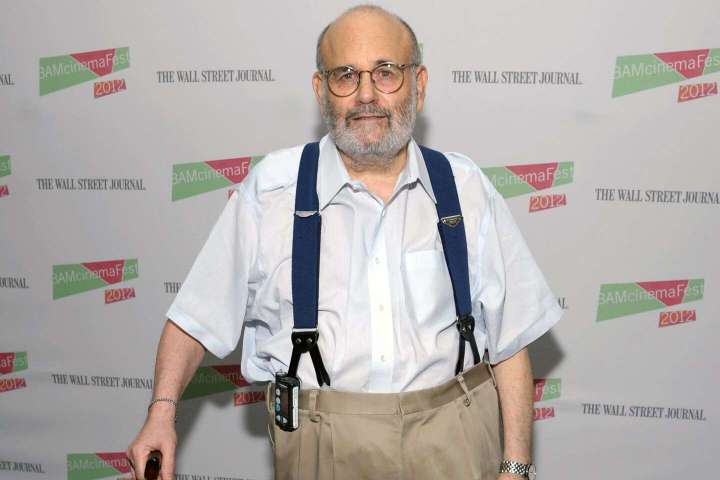

Larry Josephson, freeform radio pioneer, dies at 83

On his daily show, called “In the Beginning,” he proceeded to unload the contents of his restless, sardonic mind, helping to invent the anti-format known as free-form radio. He quickly gathered a considerable audience, reportedly around 600,000 listeners, providing a startlingly informal alternative to the hopped-up antics of Top 40 DJs and the rapid-fire flow of headlines on all-news radio.

A radiophile since childhood, Mr. Josephson was, as the New Yorker wrote in 1967, “a refreshing, honest-to-goodness human being … who presents no news, no traffic, no weather, and no cheery observations. In fact, he Hates Mornings.” Rather, writer Roger Angell noted, the stout and bearded Mr. Josephson “assaults a variety of hallowed precepts and revered institutions … orders a bagel from a nearby delicatessen, and when it arrives, eats it, audibly.”

At the height of the Vietnam War, on a station that listeners associated with hardcore leftist politics, Mr. Josephson opened his show most mornings with “Greetings, war fans!”

From that explosion of angst and wit in 1960s New York City, Mr. Josephson went on to create five decades of public radio programs, reviving the popular and influential Bob & Ray comedy team for a new generation of fans, hosting a nationally syndicated series of discussions between conservative thinkers and an argumentative but charming liberal (himself), and producing marathon readings of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” and a documentary history of the Jews.

Mr. Josephson died July 27 at a rehabilitation facility in Manhattan of complications from Parkinson’s disease, said his daughter, Jennie Josephson. He was 83.

On WBAI, Mr. Josephson mostly steered clear of politics — he called himself an “Eisenhower liberal” on a station populated by “highly principled Quakers and Marxists.” He preferred to trade puns with a quick-witted friend, play the voice of a right-wing pundit and drown it out with a Bach organ piece, air reports on life in a Manhattan private school as narrated by a 14-year-old caller, or banter with Larry the Bagel Man, who delivered his breakfast to the studio.

“In the Beginning” featured an unpredictable mix of music, as the New Yorker described: “an old pianola roll, a hymn, the Beatles, an Irish patriotic song, Judy Collins, a spiritual, a march, Simon & Garfunkel.”

For a time, Mr. Josephson continued to work afternoons as a computer analyst while spending his mornings on the air. He dropped his morning show in 1972, after his 18-month-old daughter, Rachel, died of a heart problem. He later hosted a show on KPFA in Berkeley, Calif., which, like WBAI, was part of the Pacifica Radio network of listener-funded stations. But within a few years, he wound up back in New York, where he served as WBAI’s station manager and then established a third career in a field many credit him with helping to create: as an independent public radio producer.

From a studio he built in the third bedroom of his Upper West Side apartment, crowded with antique radios, microphones and a dazzling collection of old windup toys and other gadgets, Mr. Josephson produced his own shows and those of many other mainstays of public radio.

Ed Bradley recorded his “Jazz from Lincoln Center” program in the apartment studio, Garrison Keillor read his “Writer’s Almanac” there and Alec Baldwin taped his “Here’s the Thing” podcast there. The walls were lined with framed letters from Johnny Carson, Jay Leno, David Letterman and Al Franken touting their support for Mr. Josephson’s efforts to raise money to build an audio archive of Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding’s radio comedy bits from the 1950s through the 1980s.

“He built this studio in his apartment and the world came to him,” his daughter said, recalling visits by the Rolling Stones, Al Gore and many members of the “Saturday Night Live” cast, all there to be interviewed for one or another show being produced in the bedroom studio, which he christened the world headquarters of his Radio Foundation.

Mr. Josephson almost single-handedly brought Bob & Ray’s sweetly subversive comedy to a new audience, producing their “Bob & Ray Public Radio Show” that aired on 250 stations from 1981 to 1986, as well as the duo’s live shows at Carnegie Hall.

In the 1990s, he hosted Bridges: A Liberal/Conservative Dialogue, a show on which he interviewed and debated conservatives such as economist Milton Friedman, talk host Rush Limbaugh and actors Charlton Heston and Tom Selleck. In 2007, he produced and narrated “Only in America: The Story of American Jews,” an eight-part radio documentary tracing 350 years of history. And in 2012, he performed a one-man show, “An Inconvenient Jew: My Life in Radio,” at a cafe in Greenwich Village.

Mr. Josephson’s relationship with public radio could be fractious. In later years, as public radio shifted from its roots as an informal network of stations programmed mostly by volunteers and proudly anti-establishment voices to become a more predictable and professional source of national news, talk and music, Mr. Josephson pushed back hard against what he saw as a soulless, conformist media machine.

At Pacifica, audience ratings were ignored or smirked at, he told this writer for the 2007 book “Something in the Air: Radio, Rock and the Revolution that Shaped a Nation.” “We didn’t care if three people listened,” he said. “We would have a show on Holocaust victims followed by a program on the mechanics of gay sex. There was no flow, zero. We did things because we thought they ought to be done. … You don’t sit down in a focus group and see what people want to hear.”

Public radio’s emphasis on building a large national audience meant that “there is now in public radio no place where someone like me could go on and talk about my marriages and my divorce and the death of my child,” he said. “When ‘Lady Madonna’ came out, I played it over and over for two hours because it moved me spiritually. No one would dare do that now but listeners loved it because it came from deep inside me.”

Norman Lawrence Josephson was born in Los Angeles on May 12, 1939. His father sold diamonds for a time and later worked in a variety of fields; his mother was an office manager for physicians. Mr. Josephson grew up loving radio and especially radio comedy, but he would listen to almost anything, even becoming fascinated by “The Rosary Hour,” a Catholic Church-sponsored program on which the rosary prayer was recited over and over.

He attended the University of California at Berkeley but left before finishing his degree to work for IBM. He later went back to school and completed his undergraduate degree in linguistics in 1973.

He was married and divorced twice, to Charity Alker, with whom he had a daughter, Rachel; and to Valerie Magyar, with whom he had a daughter, Jennie, a journalist. In addition to Jennie Josephson, survivors include two stepchildren from his first marriage, Gregory Alker and Rebecca Josephson; a sister; and two grandchildren.

When Jennie Josephson arrived at the rehab facility to say goodbye to her father on Wednesday night, she said, “shortly after his passing, there was static on the radio by his bed.”