Pete Carril, a Hall of Fame college basketball coach who developed a system of play known as the Princeton Offense, which propelled his undersized Princeton teams to heroic performances against NCAA Division I powers and shaped how the game is played from high school to the National Basketball Association, died Aug. 15 at a hospital in Philadelphia. He was 92.

Pete Carril, Princeton’s Hall of Fame basketball coach, dies at 92

The cause was complications from a stroke, said his grandson, Pete Carril.

As an Ivy League school, Princeton does not award athletic scholarships, and for 29 seasons — 1967-1968 to 1995-1996 — Mr. Carril prepared future lawyers, professors and government officials to take on teams stocked with future NBA draft choices, especially during postseason tournament play.

Mr. Carril designed a half-court offense demanding constant motion by all five players, with disciplined passing and quick cuts to the basket for open shots. The goal was to spread the floor, wind down the shot clock and wear down defenders until they made a mistake — or a Princeton player wriggled free for a layup or a jump shot.

“The main thing is to get a good shot every time down the floor,” said Mr. Carril, (pronounced kuh-RILL) who was inspired by the unselfish play of Bill Russell’s Boston Celtics of the 1960s. “If that’s old-fashioned, then I’m guilty.”

During Mr. Carril’s time at Princeton, his team won the National Invitational Tournament in 1975, notched 13 Ivy League titles, earned 11 NCAA tournament berths and ambushed basketball powers like UCLA, Indiana and Duke. He was the only Division I men’s coach to win more than 500 games (most of them against Ivy League teams) without the benefit of athletic scholarships, and in 1997, he was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

“We went into every game thinking we had an advantage no matter who we were playing, because we were incredibly well prepared,” Matt Eastwick, one of Mr. Carril’s former players, told the Go Princeton Tigers website in 2007. “Isn’t that the mark of a great coach?”

Yet the most famous game Mr. Carril coached was one that Princeton lost.

In the first round of the 1989 NCAA tournament, his 16th-seeded Tigers played Georgetown, the No. 1 seed, a team anchored by 6-foot-10 Alonzo Mourning and 7-foot-2 Dikembe Mutombo, both future NBA Hall of Famers.

To simulate their towering presences at practices, Mr. Carril told his assistants to hold up brooms for his much smaller players to shoot over. During pregame warm-ups, ESPN announcer Mike Gorman said Princeton, a 23-point underdog with no players taller than 6-foot-8, looked like a high school team that had stumbled into the wrong gym.

But Princeton’s zone defense forced the Hoyas to settle for outside shots, while the Tigers ran the backdoor, with players rushing toward the ball and then cutting behind their defenders’ backs to the basket for easy layups. At halftime, Princeton had a shocking eight-point lead. Georgetown came back in the second half and won by a single point, 50-49, but the game was seen as vindication for small schools and changed the nature of the NCAA tournament.

Until then, first-round games were relegated to cable TV. But the prospect of more David vs. Goliath barnburners helped persuade CBS to sign a seven-year, $1 billion deal with the NCAA to televise every game of the tournament, transforming college basketball’s March Madness into a cultural phenomenon rivaling the Super Bowl.

Before the game, NCAA officials considered revoking automatic bids for weaker conferences because their teams were often blown out. Princeton’s riveting near miss quashed those discussions and opened the door for future upsets by small schools such as Middle Tennessee State, Florida Gulf Coast, Northern Iowa and the University of Maryland Baltimore County. Sports Illustrated dubbed Princeton-Georgetown “The Game that Saved March Madness.”

Years later, Mr. Carril admitted that his goal had been far more modest. “We were trying not to embarrass ourselves,” he said.

With his gnome-like stature, droopy ears and tufts of unruly white hair, Mr. Carril drew comparisons to Yoda, the Jedi master of the Star Wars films. He prowled the sidelines with a game program clenched in his fist, beseeching his players. Once, when his center cut the wrong way, the frustrated coach ripped his own shirt in half.

“He was hard on guys and hard on me, but very rarely wrong,” Geoff Petrie, who played for Princeton in the late 1960s before joining the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers, told the Los Angeles Times. “He made an incredible career as a coach basically by outsmarting people.”

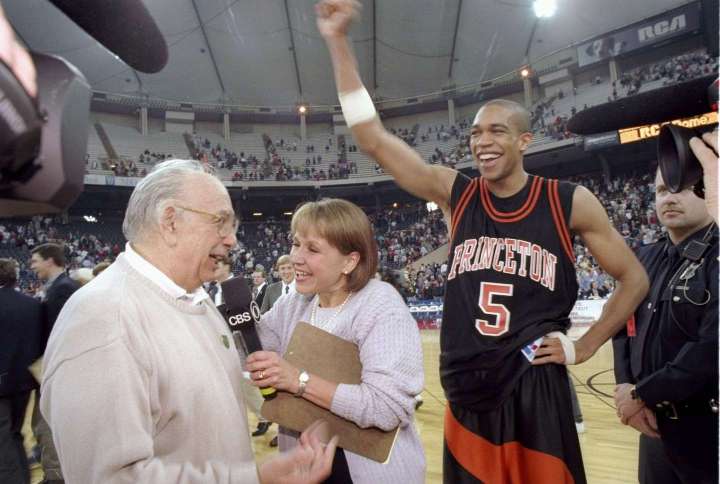

In the opening round of the 1996 NCAA tournament, Mr. Carril hoodwinked defending national champs UCLA.

To deny the stronger, quicker Bruins the fast break, he ordered his players to rush back on defense and to execute their deliberate, small-ball offense, which one sportswriter likened to “water torture.” The game went down to the wire with Princeton scoring the winning basket on a backdoor layup by Gabe Lewullis, a future orthopedic surgeon.

Despite such victories, Mr. Carril struggled to persuade high school standouts to reject full scholarships from other universities and play for him.

“Princeton can be tough to sell to a highly recruited kid,” he told the Wall Street Journal. “What can I tell him? That if he has great grades, and a 1,200 SAT score, and generous parents, we might consider letting him in?”

Peter Joseph Carril was born July 10, 1930, in Bethlehem, Pa., where his Spanish immigrant father spent decades as a steelworker and raised his son as a single father. He grew up in a $21-a month apartment where he could smell the smoke from Bethlehem Steel across the street.

Mr. Carril hustled pool and played hoops at the Bethlehem Boys Club. Though just 5-foot-7, he starred on his high school team and then played at Lafayette College in Easton, Pa. His crafty play and, later, his coaching philosophy reflected his father’s oft-repeated maxim: The strong take from the weak, but the smart take from the strong.

As a senior, in 1952, he won Little All America honors for small-college players. But after brief Army service, when he showed up for his first coaching job at Easton High School, he was mistaken for a janitor. In 1959, he received a master’s degree in educational administration from Lehigh University in his hometown.

At Reading (Pa.) High School, he compiled a 145-42 record. Then he coached for a year at Lehigh before moving to Princeton in 1967. He was hired on the recommendation of his predecessor at Princeton, Butch van Breda Kolff, who had coached Mr. Carril at Lafayette and went on to a long coaching career in the NBA.

He arrived two years after van Breda Kolff and Bill Bradley, Princeton’s greatest player and a future U.S. senator, and led the Tigers to a third-place finish in the NCAA tournament.

As larger schools became ever more dominant, Mr. Carril’s teams never advanced past the second round of the NCAA Tournament. But he won 514 games at Princeton, giving him a total of 525 collegiate victories. He shrugged off the achievement, saying, “It just means I’ve been around for a while.”

His marriage to Dolores Halteman ended in divorce. Survivors include two children, Peter Carril of Princeton and Lisa Carril of Pennington, N.J.; and two grandchildren.

After he left Princeton, Mr. Carril’s basketball philosophy gained wider currency, thanks, in part, to several of his assistants who became head coaches, including Bill Carmody at Princeton, John Thompson III at Georgetown and Craig Robinson (the brother of former first lady Michelle Obama) at Oregon State.

The Princeton Offense was even adopted by NBA teams, despite the league’s reputation for selfish, one-on-one play. Mr. Carril spent the last decade of his career, from 1996 to 2006, teaching it to the Sacramento Kings as an assistant coach.

Off the basketball court, Mr. Carril had few pastimes apart from smoking Macanudo cigars, a habit he gave up after a heart attack in 2000.

“I get my happiness out of seeing things done right,” he told the Los Angeles Times, “out of being successful, out of seeing the interaction of people working together for a good cause, spilling their hearts out on the floor, giving you the best of what they have.”