When in 1977 Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ended the “emergency” that had suspended India’s democratic processes since 1975, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a former U.S. ambassador to India, puckishly said: Wonderful news — the United States is no longer the world’s largest democracy. By next year, India will become the most populous nation. This, like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s splendidly insouciant visit to Taiwan, will diminish today’s fatalism about China — the fallacious assumption that its trajectory is inevitably upward, so it must be accommodated.

China’s decline may be looming. Here’s how the U.S. can win, if it so chooses.

Ian Bremmer of the Eurasia Group said in a recent newsletter that “the world isn’t moving in China’s direction.” After 50 years during which cheap labor made China the world’s “manufacturing engine,” Chinese labor is increasingly expensive and decreasingly abundant. A United Nations model projects China’s population, 1.4 billion today, peaking in 2028, then shrinking to 700 million to 900 million by 2100. In June, Bremmer said, a Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences issued a report — immediately suppressed — that China’s population actually peaked last year, and will decline steadily to 587 million in 2100.

With sensible U.S. immigration policies, the nation’s population in 2100 might approach that. Speaking of immigration and much else in a private talk, Norman Augustine, former defense industry leader and Pentagon official, is wise.

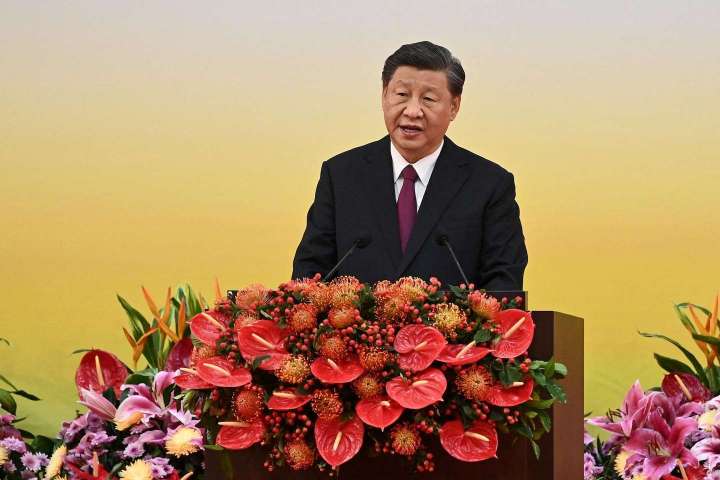

He respects China’s achievement in moving more of its citizens “from poverty into the middle class than there are Americans to move anywhere.” And he agrees with Chinese President Xi Jinping that “technological innovation has become the main battleground of the global playing field.” Augustine notes:

Follow George F. Will‘s opinions

Follow“In the year 2000 the U.S. graduated 1.9 times as many scientists and engineers at the baccalaureate level as China; but, by 2020, China was graduating 2.4 times as many as the U.S. At the doctorate level, the U.S. lead was a factor of 3.3, whereas today China leads by a factor of 1.1. If one excludes Chinese nationals who graduate from U.S. universities, that factor becomes 1.3 – and is rapidly increasing.”

A Chinese high-school graduate has had nearly three more years of classroom education than an American counterpart, Augustine says, “simply due to the length of the respective school years.” The standardized U.S. test called the Nation’s Report Card rates 76 percent of 12th graders below proficient in math and 78 percent below proficient in science. Augustine notes acidly that increased spending on K-12 education has enlarged schools’ administrative staff 88 percent while student enrollment has grown just 8 percent.

In the percentage of all baccalaureate degrees granted in engineering, the United States ranks 76th globally. Twenty-three percent of U.S. PhDs are in science, technology, engineering or mathematics; in China, 79 percent. Augustine says a “substantial” reason for U.S. proficiency in STEM subjects is immigration: 28 percent of U.S. university faculty members in science and engineering were born abroad, as were 38 percent of American Nobel laureates in chemistry, physics and medicine since 2000. “And nearly half of U.S. Fortune 500 companies had a founder who was an immigrant or the child of an immigrant,” Augustine says.

America’s choices can win the competition with China. The United States can choose more-welcoming immigration policies, including retaining foreign nationals who earn about one-third of science and engineering PhDs from U.S. universities. The U.S. government can choose to spend much more than 0.2 percent of GDP on basic research. (This percentage has declined in 20 of the last 28 years, and now ranks 29th globally.) The United States has, after all, 16 of the world’s 25 best universities, according to the Times Higher Education 2022 ranking. And while China’s allies (North Korea, Iran, Russia) represent 17 percent of global GDP, the United States and its closest allies — counting just Europe and Japan — represent almost 50 percent.

Meanwhile, China is choosing to make itself stupid. The Financial Times reports that China’s youth unemployment is 18.4 percent and university graduates are struggling to find work — “unless they have degrees in Marxism.” In 2018, the education ministry ordered universities to hire at least one Marxism instructor for every 350 students. In this year’s second quarter, there was a 20 percent increase, over the same period last year, of job openings requiring a Marxism degree. Good: Marxism makes adherents stupid. All those brain cells devoted to a 19th-century prophet whose prophecies have not fared well.

A 20th-century paradox: If the 1917 revolution had not infected Russia with communism, there would have been no Cold War; but communism’s stultifying irrationalities determined the war’s fortunate outcome. A 21st-century probability: China’s Leninism — everything is subordinated to the party’s “vanguard” function, and the party is the vanguard of ignorance — will similarly determine China’s trajectory.