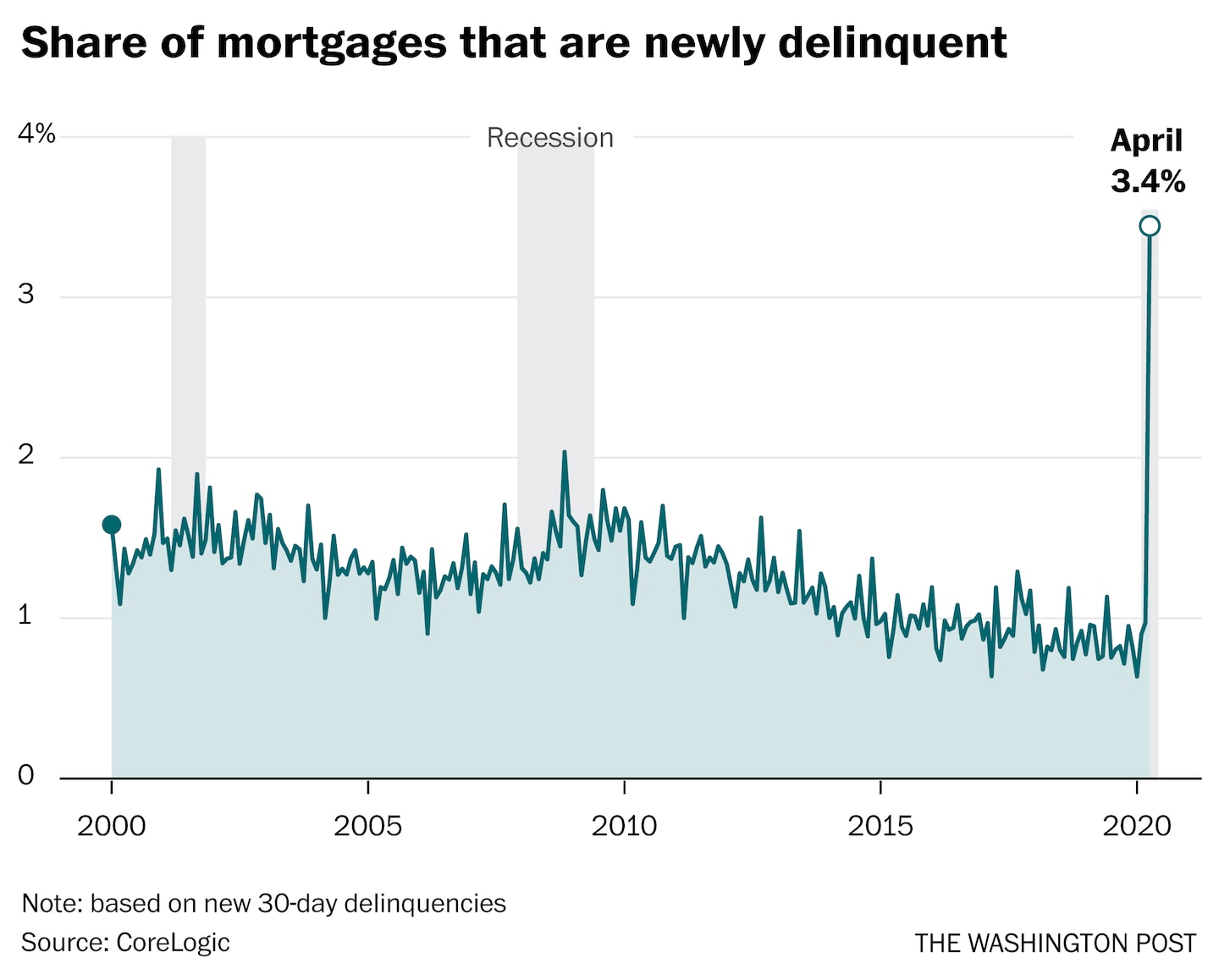

An indicator that presaged the housing crisis is flashing red again

Mortgage delinquencies were among the first signs of the housing crisis and can signal underlying weakness in the housing market. But does the surge in delinquency mean a second housing crisis looms with a wave of foreclosures?

Probably not. As with most data released during this coronavirus period, these figures come wrapped in caveats and uncertainty.

For starters, the new delinquency figure includes an unknown number of households that are late on their payments because their loans are in forbearance, said Frank Nothaft, CoreLogic’s chief economist. On March 27, President Trump signed the Cares Act, which made it easy for qualified homeowners to request a total of 12 months of mortgage forbearance. That leaves a small window in which the first homeowners who applied for forbearance could show up in the April data.

The forbearance program has been wildly popular. The Mortgage Bankers Association reports 4.1 million households were in forbearance as of July 5. To be sure, many applied after the April period measured here, and not all who apply for loan deferrals will actually fall behind on their payments. The program was broad, and many homeowners took advantage of the loan reprieve as a precautionary measure.

Millions of Americans who didn’t have a loan backed by the federal government weren’t eligible for the program. “There are some loans that are not in forbearance that are going right into delinquency,” Nothaft said.

There are endless reasons to fall behind on your payments right now. About 33 million people have lost their jobs and are receiving jobless benefits, Labor Department data show. The unemployment rate in April was at its highest since the Great Depression, plunging millions into dire financial situations, and the Federal Reserve projects unemployment will remain near double digits through the end of the year.

Even excluding mortgage loan deferrals, a Census Bureau survey shows that as of June 30, about 8.4 million households missed a mortgage payment in the past month. That’s up from the end of April, when it stood at about 5 percent.

“I do think we’re going to see further increases in delinquency rates,” Nothaft said. And a year from now, if the economy hasn’t improved substantially by the time forbearance runs out, “you could be looking at a prospect where the lender begins foreclosure proceedings.”

Delinquencies are concentrated in the Northeast and South, often in states harder hit in the earlier stages of the pandemic.

If delinquencies continue to follow the virus, they could become a national phenomenon in the months to come. CoreLogic’s models forecast serious delinquency rates will quadruple during the next 18 to 24 months, meaning about 3 million borrowers could be at risk of losing their homes.

That’s not to say the coronavirus crisis will be a repeat of the Great Recession. Almost 4 million homes were lost to foreclosure between 2007 and 2010, according to an analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, but the housing market is much healthier now. Subprime mortgages are rare, and homeowners have far more equity in homes. That leaves them in a much better position to weather a downturn and less likely to walk away from their homes when things go south.

“Right now, there isn’t any risky behavior that’s resulting in a big rise in delinquencies,” said Redfin lead economist Taylor Marr.

The housing market looks strong for now. There were 22 percent fewer homes for sale during the week ending July 4 than there were at the same time last year, according to Zillow, and ultralow interest rates have ensured steady demand from buyers. Low supply and high demand have had a predictable effect: Home prices are still climbing.

That may change next year. If delinquencies lead to foreclosures, as the forbearance time period expires, we could see an increase in the number of properties on the market. It may be compounded by other stressed buyers, who need to cash out of their home to pay bills as the recession continues. The supply glut could increase further if shutdowns are lifted and homeowners who held off on selling during a pandemic suddenly flood the market. On the demand side, there are fears buyers could pull back as stimulus fades and unemployment remains high.

Nothaft estimates home prices will fall about 6.6 percent from this May to the next. Mortgage giant Freddie Mac forecasts flat home prices next June. Redfin’s Marr, while optimistic, also says falling home prices are possible. However, he said, the supply glut could be alleviated by the long-awaited influx of first-time millennial home buyers, as well as the myriad forces that have prevented home builders from fully meeting demand.

Like so many things right now, the future of the housing market ultimately depends on how quickly the novel coronavirus can be contained and whether the government’s stimulus programs will be extended as the pandemic drags on.

“I would say the risk of a massive wave of foreclosures is pretty low,” Marr said. “I have high hopes that the government and other agencies will do what they can to keep people in their homes.”

Kathy Orton contributed to this report.