Anthony Fauci built a 40-year truce. Now war is coming.

“Where’s Fauci?”

It has been one of the many nagging worries of 2020: Is the famous immunologist still on the case? (Yes, but he is so busy he can barely make time to talk.) Is he about to get fired? (Almost always and probably never, but we’re going through another round of White House scapegoating right now.) Is he still speaking with the president? (He is, but their interactions have become fewer and further between.)

But at least as important as where Anthony S. Fauci might be is where the good doctor has already been.

You don’t get Fauci bobblehead dolls, or Fauci-faced doughnuts, or Brad Pitt playing Fauci on “Saturday Night Live,” or all that hand-wringing over his whereabouts unless there’s something unusual going on.

We the people have put our faith in Fauci for nearly 40 years, even as trust itself has become almost obsolete. Conservatives as conservative as Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) have leaped to his defense on Twitter when he’s been attacked, calling him “one of the finest public servants we have ever had.” When Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) chastised him in a congressional hearing, the contrarian lawmaker felt compelled to add the grudging coda, “as much as I respect you.”

Science and partisan politics seem, in our era, inherently in conflict. One runs on fact-centered reality, the other on point-scoring spin. Yet Fauci more than any other figure has brokered a generational peace between the two worlds. Now that the coronavirus pandemic has divided an already riven country between those who believe the disease is an all-consuming danger and those who believe it is dangerously overblown, it is fair to ask: How did this man get to be the singular referee the country trusts — and how are we ever going to manage when he is gone?

We’ve already had a taste of the latter. Everyone, from citizens to celebrities to elected officials, has been playing hide-and-seek with Fauci as he has appeared, and disappeared, and appeared again over the past four months.

At first, as soon as Fauci was anywhere, he was everywhere. The New York Times dubbed him the explainer-in-chief for all things coronavirus, and he did his explaining to Laura Ingraham and Chris Cuomo, in the largest papers and the littlest websites, on the early morning rundowns and the noontime Sunday shows. He showed up to chat with Trevor Noah and Stephen Curry. He told us what we should worry about, what we shouldn’t worry about and what we didn’t know enough about to say whether we should worry.

Observers panicked when he failed to appear at a news conference, but then he would reappear at the next one and they would exhale. Reporters suggested the president’s patience with Fauci was thinning, perhaps because he kept correcting the commander in chief’s many incorrect statements. Yet even President Trump at times has shown his appreciation, though it tends to come under very particular conditions. “Thank you Tony!” Trump tweeted at one point, responding to a televised compliment from the doctor by portraying the two as fast friends.

President Trump speaks with Anthony S. Fauci at the White House on April 22. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

President Trump speaks with Anthony S. Fauci at the White House on April 22. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post) With Fauci, there is feast, and there is famine. In May, the steady stream of appearances slowed and then appeared to peter out entirely, except for an errant and anodyne appearance on, somewhat inexplicably, actress Julia Roberts’s Instagram. The White House task force, rumors whispered, was getting dismantled — or, no, it was only getting scaled back. “Why Is Dr. Fauci Suddenly Off the Air?” asked Vanity Fair. “Forgotten Fauci?” wondered Forbes. “Fauci conspicuously stops doing TV interviews as White House moves to reopen economy,” CNN declared.

As the rolling averages of new cases in 33 states ticked precariously upward, we had what looked like a second coming of Fauci: more interviews warning that we can’t anticipate normalcy in less than a year — in British media telling U.K. tourists not to expect to come here on holiday and in esoteric sports blogs complimenting the NBA’s back-to-action plan (though, curiously, less frequently on major television outlets). “100,000 cases a day,” Fauci warned in congressional testimony on the last day of June.

And then, as if those warnings had been too dire for the administration to bear, he faded again. By mid-July, the White House was saying Fauci had been too wrong too often, laying out a number of times when he missed a call early on in the pandemic — when the whole world was operating with limited information. “He wants to play all sides of the equation,” the president added in one criticism of the doctor.

In reality, Fauci has only ever wanted to play on the side of science, and until now, all the other sides in the Washington game have been willing to let him do it. Can the peace Fauci has forged over almost four decades last when one of the parties isn’t willing to honor the treaty’s terms?

Anthony S. Fauci’s father, Stephen, stands in front of his pharmacy at 13th Avenue and 83rd Street in the Dyker Heights section of Brooklyn, circa 1950. The family lived in the apartment above. (Courtesy of Anthony Fauci)

Anthony S. Fauci’s father, Stephen, stands in front of his pharmacy at 13th Avenue and 83rd Street in the Dyker Heights section of Brooklyn, circa 1950. The family lived in the apartment above. (Courtesy of Anthony Fauci) The country is lucky a young Tony Fauci didn’t have to look too far to find medicine — in fact, it was always just downstairs. In the 1940s, the Faucis lived in an apartment above their drugstore near the intersection of 13th Avenue and 83rd Street in Brooklyn’s Dyker Heights neighborhood. His pharmacist dad, named Stephen but nicknamed Doc, took care of the dispensing; his mother, Eugenia, and his older sister, Denise, ran the register. Tony rode his bicycle like so many other boys — except he was carrying prescriptions for customers in a little basket on the front of his Schwinn, delivering cures to the sick long before he was developing them and, if he was fortunate, earning a two-bit tip.

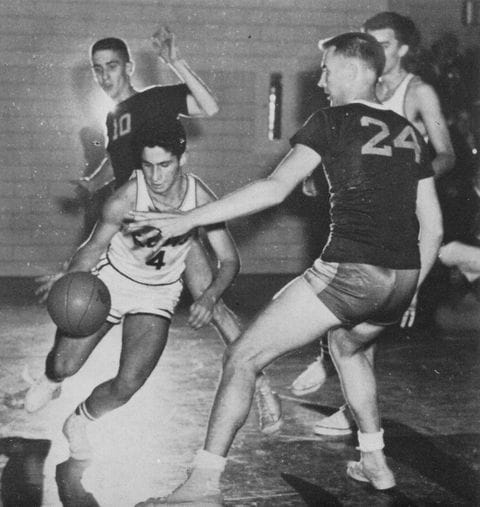

Across the street from the pharmacy was the Shrine Church of St. Bernadette, host to masses and sacraments but also to something far more tempting to a 10-year-old kid: sports. Fauci won a trophy in his first year on the parish bantamweight basketball team and went on to play at Regis, a storied Jesuit high school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. “All you really need to know about Tony Fauci,” says Jack Rowe, a former president and chief executive of Mount Sinai NYU Health, “is that, at five-foot, seven-inches, he was the captain of his high school basketball team.”

Anthony Fauci played high school basketball at Regis, a storied Jesuit school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. “All you really need to know about Tony Fauci,” says Jack Rowe, a former president and chief executive of Mount Sinai NYU Health, “is that, at five-foot, seven-inches, he was the captain of his high school basketball team.” (Courtesy of Anthony Fauci)

Anthony Fauci played high school basketball at Regis, a storied Jesuit school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. “All you really need to know about Tony Fauci,” says Jack Rowe, a former president and chief executive of Mount Sinai NYU Health, “is that, at five-foot, seven-inches, he was the captain of his high school basketball team.” (Courtesy of Anthony Fauci) Fauci put in the hours. Some evenings he’d play “double-duty basketball,” practicing first at school and then heading up to Harlem or the Bronx to scrimmage. “I would take a bus from in front of my house to a local to an express to another local to another express,” Fauci told me. “I would sometimes play four hours or five hours of basketball, study for three hours, then get up and start it all over again.” (His days aren’t any shorter now; NIH co-workers leave notes on his windshield urging him to stop making them feel guilty and go home a little earlier, please.)

Happily for those who place a higher premium on a coronavirus vaccine than an impeccable jump shot, basketball would not be Fauci’s destiny. The family business and the exhortations of the Jesuits formed a heady cocktail that attracted him to medicine and service. He took the pre-med track at Holy Cross but enrolled in what he calls “a strange program” that combined the typical medical training with Greek classics: “philosophy, metaphysics, philosophical psychology, ethics, epistemology.” College taught Fauci how to understand the body, but it also taught him how to think about the soul.

Then came med school at Cornell. One summer before enrolling, Fauci worked on a construction crew erecting the graduate institution’s new library in Manhattan. “I remember we used to hang around and eat our sandwiches and drink our sodas, and one lunchtime I walked into the auditorium.” He was caked in concrete and plaster, with his hard hat on his head. Soon a security guard arrived and asked him to leave; his work boots were dirtying the floor.

Fauci looked at him and proudly announced that one of these days he’d be attending lectures in that very room.

“Yeah, sonny,” the guard laughed. “And one of these days I’m gonna be police commissioner.”

Anthony Fauci, circled, received his medical degree from Cornell University Medical College in 1966. He then completed an internship and residency at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center. (Courtesy of Anthony Fauci)

Anthony Fauci, circled, received his medical degree from Cornell University Medical College in 1966. He then completed an internship and residency at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center. (Courtesy of Anthony Fauci) Tony Fauci’s patients were dying. This wasn’t only upsetting for a young doc — it was new. His initial years at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) laboratory at the National Institutes of Health near D.C. were spent developing therapies for fatal inflammatory maladies that somehow, in his hands, weren’t fatal anymore. Polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis and lymphomatoid granulomatosis never earned acronyms in popular parlance, and they hardly made Fauci famous — but they did command him early respect within his field. Other doctors had told people they had only years or months left. Fauci was developing therapies that delivered real lifetimes instead.

HIV/AIDS, in contrast, was an abyss. The disease, suspected to have originated around 1920 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was by 1980 infecting hundreds of thousands in the United States without anyone knowing much about it. Fauci certainly knew very little when he read in the summer of 1981 about a rare opportunistic pneumonia in five once-healthy patients in Los Angeles; weeks later, he encountered another medical journal piece about a group in New York, as well as one in San Francisco, with the same malady.

All the subjects were men, and all the men were gay. Fauci knew it wasn’t a coincidence. He shifted his lab’s focus to AIDS, contrary to the advice of his mentors. He turned to investigating exactly what HIV was doing to the immune systems of those it afflicted: devastating the T cells that normally kill intruders, as well as making the antibody-producing B cells go haywire. Fauci admitted his first AIDS patient to the NIH Clinical Center in January of 1982. He went from most of his patients surviving to none.

AIDS was far from only a medical challenge. Talking about homosexuality in the public square was uncommon 40 years ago; talking about a sexually transmitted virus that was ravaging the gay community was rarer still. Millions of Americans ignored the peril, wishing the whole thing away, and amid the ignorance misinformation flourished — suggesting, for instance, that people were putting themselves in jeopardy by touching the infected or merely passing them on the street. Scaremongering moralizers weren’t treating the enemy as natural, but as divine: a punishment for the freewheeling lifestyle of city dwellers, drug users and of course the favorite boogeyman of the bigoted: homosexuals.

It didn’t help that politicians wouldn’t talk about AIDS either. President Ronald Reagan didn’t utter the word until his second term — but he was only the biggest man among many who preferred to ignore a burgeoning genocide because it could prove inconvenient to do otherwise. And then there were Fauci’s fellow scientists, who held sway over what research to do with scarce dollars.

So the doctor would have to win over the politicians and win over the scientists. But before that, he had to win over the activists.

Those activists, as veteran AIDS organizer Peter Staley put it, were “a scary bunch,” and because Fauci was the bespectacled face of the slow-to-act federal medical bureaucracy, they trained their fire on him. Fauci had realized by 1984, the year the world posted its greatest increase in HIV infections and eight years before the disease’s peak in the United States, that he finally had a reason to take a job he had tried to avoid: director of NIAID, the government arm for research on infectious, immunologic and allergic diseases. Only then could he occupy a perch prominent enough to get the money and attention needed to address what he guessed was the “emerging disease that would dominate the field” of medicine. (“Unfortunately,” he tells me, “I was correct.”)

Dr. Fauci with an AIDS patient in 1987. (Courtesy of NIAID)

Dr. Fauci with an AIDS patient in 1987. (Courtesy of NIAID) Fauci accepted the role on the condition that he could continue to see patients and work in his lab — a deal he retains today, 36 years and five presidents later. His perch, however, also meant some unpleasant attention. Fauci’s bloodied likeness was held aloft on a pole outside NIH headquarters; his effigy was burned; his motivations and morality were assailed as suspect. Larry Kramer, the playwright and venerable AIDS activist who died in late May, summed it up in the San Francisco Examiner, calling Fauci “an incompetent idiot.” The NIH, Kramer declared, was an “Animal House of Horrors.” Fauci was a “murderer.”

“It doesn’t take a genius to set up a nationwide network of testing sites, commence a small number of moderately sized treatment efficacy tests on a population desperate to participate in them, import any and all interesting drugs (now numbering approximately 110) from around the world for inclusion in these tests at these sites, and swiftly get into circulation anything that remotely passes muster,” Kramer wrote. “Yet, after three years, you have established only a system of waste, chaos, and uselessness.”

The activists wanted access to experimental drugs that they believed they would perish without — drugs that were held up in the regulatory approval process and available only through controlled trials limited to a tiny portion of those infected. They wanted to stop going through “buyers clubs” to get drugs they thought might save them; they also wanted a seat at the table where the decisions about medicines — and how they were okayed — were made. “Some people would hide behind the walls of academia and cloak themselves in the mantle of science and ‘we know better,’” says Peggy Hamburg, a former Food and Drug Administration commissioner and one-time employee of Fauci’s. “Tony decided to open the door and let them in.”

Literally. At one of these NIH protests in October of 1988, the police had arrived to arrest the demonstrators, and Fauci suggested they bring some of the leaders up to his conference room instead. Most scientists at the time, he says, would have “run for the hills.” And yet, as comfortable as the doctor may have been so near to his laboratory, the activists were less at ease. In later meetings, the two sides needed some neutral ground. The solution: Fauci had a deputy named Jim Hill, who was gay and a talented cook, with a townhouse on Capitol Hill — the ideal place for both sides to disarm. It was, explained Staley, “Switzerland.”

“Getting the Tony Fauci treatment one-on-one for three hours over wine, you would just become an ineffective blubbering sycophant by the end of it,” he added. The activists’ strategy was to go in groups and to then conduct a post-mortem on the drive back to New York. “We wanted him to drink more wine than we did so he would get a little loose-lipped and tell us what was really going on.” Soon enough, Fauci was convinced that the people dying of AIDS should have a role in the process designed to make the dying stop — meaning they ought to participate in agenda-setting committees at NIAID. The challenge was convincing his colleagues of the same thing.

Many NIH scientists wanted nothing to do with AIDS at all, in part, Fauci suspects, because of prejudice against the gay men and drug addicts the disease was chiefly killing. And even the investigators running the trial process were resistant to any demands, insisting they stood on the principle of good old-fashioned, take-it-slow science. This was the way they had done things, forever. Who were these laymen telling them to change? They were ravaged by disease, yes, but they were ravaged also by the enemy of objectivity: emotion.

When Fauci realized some on his NIAID team would never budge from that view, he fired them. The others, well, “they’re smart, these scientists,” he remembers. “They said, ‘Now, well, Tony is right. If we really want to get a trial going, we have to sit down with the people who are going to be in the trial.’”

Still, AIDS was much faster at killing than the FDA was at greenlighting drugs. Fauci decided that the infected should have access to drugs that had progressed only part-way through the approval process. This was unthinkable in the late 1980s, and it was a question for the FDA, not the NIH. So Fauci decided to get the rest of the country involved. At the 1990 International AIDS Conference in San Francisco, he endorsed allowing infected people to have access to drugs still in the trial process. The activists heard it; the press wrote about it; the nation witnessed one of its top doctors calling for an unprecedented breaking of the rules that had governed infectious diseases for decades.

This was the birth of the Fauci protocol. The diagnosis he drew from the activists: Science and politics aren’t independent; they’re inextricably intertwined. The treatment he learned from his colleagues: To ensure that science and politics bring out the best in each other, isolate them despite their seeming entanglement. He put the two lessons together, and came up with his signature bedside manner. Argue the science for science’s sake, and ignore the rest. “It isn’t really politics,” Fauci explains. “It’s staying out of politics. What I learned is don’t be political. Be medical. Be scientific. … It’s when you get into the politics that you get in trouble.”

Conveniently, this cure worked on the politicians, too. Reagan hadn’t wanted to mention AIDS at all; Fauci insists this wasn’t because he was a bad guy but because he was surrounded by conservatives who wouldn’t let him get away with it. So Fauci took point on government PR, pioneering his now-famous strategy of appearing in outlet after outlet until the public practically developed a Pavlovian reaction to his presence: This guy is the nation’s family doctor, and what he’s saying is probably right.

Other elected officials discovered Fauci might be on to something. Here was a man who put a focus on the defining crisis of the day and actually did something about it — all the while framing that crisis merely as a question of scientific truth. As long as Fauci was credible, these politicians could launder credibility through him, all the while holding at a distance the more radioactive elements of any crisis. They could immunize themselves to criticism because they had a guy always sitting staunchly in the middle speaking for them.

“Once you get tagged as being in a political camp,” says Fauci, “you lose your credibility right away.”

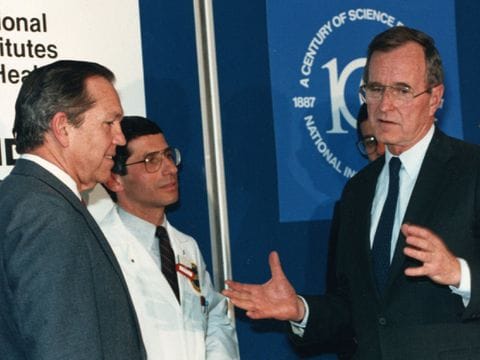

The Fauci protocol wasn’t beneficial only for Fauci’s patients. George H.W. and Barbara Bush knew a lot about hospitals. They had all but moved into one in New York City before their second child, Robin, died of leukemia in 1953 at age 3. Bush visited the NIH when he was Reagan’s right hand, turning up with his wife, Barbara, and sitting in a room with AIDS patients, which many Republicans at that time would not have done. He took enough of a liking to his NIAID guide that he started inviting him to the Naval Observatory, to lunches and brunches, all in the lead-up to the 1988 election.

That fall, during one of the presidential debates, Bush and Michael Dukakis were asked to name someone they considered a hero. Dukakis garbled his answer; Bush named Fauci. And, keen to be a kinder and gentler version of Reagan, he kept doing it.

Who was advising him on AIDS? “My conscience has been advising me on AIDS,” Bush told the press pool on Air Force Two. Oh, and Dr. Fauci.

Should the budget make room for more AIDS research money? No, because Dr. Fauci had said so. (Overall, during Bush’s tenure the NIH budget went from paltry to plentiful.)

Ought the United States to take a more aggressive role in world leadership on the disease? Yes, because Dr. Fauci had said so.

Vice President George H.W. Bush visits the National Institutes of Health in April 1987 and discusses the HIV/AIDS program with the NIH director James B. Wyngaarden, left, and NIAID director Anthony Fauci, center. (Journal of Clinical Investigation via NIAID)

Vice President George H.W. Bush visits the National Institutes of Health in April 1987 and discusses the HIV/AIDS program with the NIH director James B. Wyngaarden, left, and NIAID director Anthony Fauci, center. (Journal of Clinical Investigation via NIAID) Bush and Fauci became pals — and both men benefited. Fauci moved to the inner circle of a White House where expertise was prized and career government officials were routinely praised. And Bush continued to drop the scientist’s name (which means “jaws” in Italian), including in Rome, when he once told the prime minister how much he admired Italian Americans such as Joe DiMaggio, Antonin Scalia — and, of course, Tony Fauci. “When in Washington, be nice to everybody, because you never know where they’ll end up,” Fauci says. “Well, my friend the vice president wound up being the president.”

Bush offered Fauci the job of NIH director multiple times. Fauci always declined it. His job allowed him to stay close to the science, to be socially distanced from the politics — and to collect the credibility that came with that stance.

Administrations to come continued to lean on Fauci as their public health go-to, even in areas in which, at least initially, he was hardly an expert at all — malaria, measles, tuberculosis, swine and bird influenza, even anthrax. Rep. Donna Shalala (D-Fla.) knew Fauci well in her time as secretary of Health and Human Services under President Bill Clinton, and she used him well, too: “We had a commitment to science, and to not simply listening to the scientists but putting them in front of [the public],” she told me. Shalala often sent Fauci to the Oval Office when Clinton’s aides told her she had an hour with the commander in chief to do with what she wished. When Shalala asked Fauci to speak to the country, she had a special request: “Put on your white coat … because people trust the doc.”

Ron Klain, who coordinated the federal Ebola response under President Barack Obama, had a similar prescription a decade later. “When public fears would rise … and people would say, ‘Hey, what should we do?’ I had a slogan I would send in emails: PTFOTV. Put Tony Fauci On Television.”

Fauci quickly developed a reputation as an A-list party get in D.C. social circles — which let him keep NIH’s needs and priorities front and center for lawmakers, editors and other politerati. He moved freely between TV green rooms, think-tanks and the city’s tonier salons, mixing easily among both Democrats and Republicans in an age when straddling the aisle had ceased being normal or, for most people, even possible.

Fauci’s golden age coincided with patronage from presidents of both parties, and it was a Republican who presented Fauci with an opportunity he could not have anticipated two decades before when his mentors told him to stay away from AIDS research. Someone else had tagged along with George and Barbara on that initial NIH visit back in 1987. George W. Bush fits well into Fauci’s be-nice-to-everyone credo: His friend the vice president’s son wound up being the president’s son, and then wound up being the president himself. Fauci had worked with the younger Bush right after 9/11 to think about bioterrorism, and soon the 43rd president was asking him to do a bit of augury and predict the next big threat that could bring down the world. Something naturally occurring, Fauci replied, like HIV — because while this country had made progress, people in other places were still dying as inevitably as all those early patients he had lost.

Bush had wanted to know whether anything could be done about that, and when Fauci said yes, Congress said yes, too.

President George W. Bush presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases, at the White House on June 19, 2008. (KAREN BLEIER/AFP via Getty Images)

President George W. Bush presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases, at the White House on June 19, 2008. (KAREN BLEIER/AFP via Getty Images) The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, launched in 2003, has saved more than 17 million lives at a cost of $90 billion. The program gives regions still buckling under the disease the same wherewithal as their wealthier peers to beat it back, by beefing up prevention efforts and also by improving care and treatment. PEPFAR is easily Bush’s crowning achievement abroad, and many of the countries in Africa initially targeted with help haven’t forgotten it: Ghana named a major artery “the George Bush Motorway.”

“Important, transforming things happen when you have a number of stars aligned in the right place at the right time, kind of like in the universe the stars are aligning once every 1,000 years together in a certain way,” Fauci said, talking about PEPFAR.

Of course, he had spent some time reaching into the sky to move things around. So it must have been surprising, all this time later, to find himself floating in a galaxy that refused to budge.

The People’s Republic of China posted the genetic code for the novel coronavirus on the Internet on Jan. 10.

The very next morning, on Jan. 11, Fauci called up Barney Graham, deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center at NIH, and told him to strap in for speed. Normally, it takes several years and hundreds of millions of dollars to make a vaccine. A year for animal studies, then a year for trials among healthy young people, then a year for trials among risky populations and then, finally, a year for a randomized trial of, say, 30,000 people or more.

Fauci said that wouldn’t be fast enough this time. They had to do it all at once. The two scientists pulled biotechnology companies into the process that same day. The firms were concerned that going at warp speed would cost a fortune. “I told them don’t worry about the money,” Fauci says. “This is an emergency. We will find the money. Go ahead and do it.”

Sixty-five days later, human trials began on Moderna’s vaccine formula. That pace, says Fauci, is “the fastest that’s ever been done since the time a virus was sequenced.” On July 27, Moderna will begin a 30,000-person final-stage trial of the vaccine. Which is a reminder that whatever other tests Fauci would face as the coronavirus emerged in the United States, doubts about his determination, budgetary clout or sway among fellow scientists were no longer among them. The politics, however, were another matter.

Fauci hadn’t met Trump before the pandemic. He arrived armed not only with his crisis-response know-how but also with his well-worn knack for soothing a terrified country. The hope was for Fauci to help the White House as he had helped others before it, and all they had to do was get out of the way. But when has Trump ever gotten out of the way for anyone?

Experts often ran screaming from Trump’s circle not long after his inauguration; civil servants who had served heedless of the R or D next to a president’s name resolved that this president was so aberrant they could serve no longer; and Trump celebrated the atrophy across agencies as victories against “the deep state.” But while the country might be able to skate by for a while without the man at the Agriculture Department who monitored sugar beet harvests or the woman at Commerce measuring rail car loadings, it couldn’t survive long without the guy at NIH who kept his eye on killer germs. Fauci stayed at his post. He, more than anyone else, had built his career on the received wisdom that the science doesn’t change depending on who’s in charge.

So Fauci quietly ordered up the trials, kept his eyes on the science and tried all spring to act as a voice of calm and reason in the looking glass, sound stage world of Washington. A reporter implied a few months ago that Fauci might have been coerced when he walked back a minor criticism of the White House — and the charge of even sounding political seemed to cut deep: “Everything I do is voluntary, please,” he said. “Don’t even imply that.”

There are times that this tip-toeing has saved lives. Fauci and White House coronavirus response coordinator Deborah Birx fought for a 15-day nationwide shutdown in March when hospitals warned they’d soon run out of ventilators, and then they fought for extending the pause a month more. There are times, though, that foot-stomping seemed the right call.

White House trade adviser Peter Navarro reportedly urged the administration to extol the unproven drug hydroxychloroquine in a meeting, and when Fauci gently argued against taking so great a leap based solely on anecdote, Navarro pointed to a pile of studies on the subject: “That’s science,” he scolded the scientist, “not anecdote.”

The president went up on the podium and told civilians to toss back some hydroxychloroquine; Fauci later appeared on television to say, in his facts-only tone, that “the scientific data is really quite evident now about the lack of efficacy for it.” In June, the World Health Organization dropped the drug from its coronavirus treatment studies.

The president has speculated about whether we ought to inject ourselves with bleach or cleanse our bodies of coronavirus particles with ultraviolet light. The president has called the coronavirus the “China virus” and then the “Wuhan virus”; he has argued against his own people’s guidance on safe reopening protocols for local officials. He has called the State Department the “Deep State Department.” With that, Fauci brought his palm to his face. He later explained that he was choking on a cough drop.

The president spread this nonsense at times with Fauci standing beside him from the podium, in what is surely a test of Fauci’s patience (as well as the public’s appetite for farce). Yet what’s the alternative? The argument for Fauci saying more than Fauci has said so far is also an argument for self-exile, and we’re better off with the doctor in the room than out of it.

Depending on the day, Trump seems to think he’s better off with the doctor around, too. Where others might have long ago been thrown out of the building, Fauci survives somehow. When Trump retweeted a missive with the hashtag #FireFauci in April, sparking some understandable panic, he walked back his statement, just as Fauci had earlier walked back his own. “Not everybody is happy with Anthony, not everybody is happy with everybody.”

“We saved millions of U.S. lives.! Yet the Fake News refuses to acknowledge this in a positive way” the president tweeted. “But they do give Dr. Anthony Fauci, who is with us in all ways, a very high 72% Approval Rating. So, if he is in charge along with V.P. etc., and with us doing all of these really good things, why doesn’t the Lamestream Media treat us as they should?”

….Dr. Anthony Fauci, who is with us in all ways, a very high 72% Approval Rating. So, if he is in charge along with V.P. etc., and with us doing all of these really good things, why doesn’t the Lamestream Media treat us as they should? Answer: Because they are Fake News!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 23, 2020

The benefit to Trump is obvious: He wants a vaccine, of course, but he also wants to absorb Fauci’s credibility by osmosis, just as other politicians have done for years. That’s why Trump put Fauci on the stage during the early months of the virus and why he put him on the stage again in early June to announce the so-called Operation Warp Speed. It would be more than a month before the two men spoke again.

“I think the president doesn’t dare fire him,” says Shalala. “They need him for cover. They need him at least to give the impression that they’re following the science.” Tom Scully, who worked with Fauci as a senior administration official under both Bushes, agrees. “Fauci is the equivalent of Mother Teresa. There are just some people it doesn’t make sense to go after.”

And yet. The White House continues its attacks, subtly on some days, not so subtly on others. This week began with an anonymous dump of quotes from the administration to the media designed to show the doctor being “wrong”; soon after, Navarro penned an op-ed for USA Today that begins, “Dr. Anthony Fauci has a good bedside manner with the public, but he has been wrong about everything I have interacted with him on.” Peak absurdity of the colleague-on-colleague pile-on arrived when deputy chief of staff for communications Dan Scavino shared a cartoon of Fauci as a faucet dumping cold water on the economy to send it spinning down the drain.

In an interview with the Atlantic, Fauci would dismiss this onslaught as “bizarre.” Trump, for his part, demurred: “I have a very good relationship with Dr. Fauci,” he said on Wednesday. Back in early June, Fauci had echoed the sentiment. He insisted to me that the ups and downs of his relationship with the president are mostly a manufactured narrative — a story some factions may want to read or hear as they sit at home desperate for heroes and villains. Ever the gentleman, he rolled his eyes at the tales. “The president has always listened to me respectfully,” he says. “Our relationship is a good relationship.”

But now the virus is surging again. Fauci is working nonstop, half the time running the $6 billion infectious disease lab he built at NIH and half the time at the White House on the task force. He wakes up and asks his wife what day it is: “Is it Easter? It is the Fourth of July?” He hasn’t had a break in months because there’s just too much to do and too many people dying. “I keep getting asked, ‘Do you think there will be a second wave in September or November?’” says Fauci. “We’re not even out of the first wave yet. We are totally immersed in the first wave.” There’s a message he wants to send, especially to young people he believes are getting tired of being cooped up as the summer slogs along: Don’t hop over the guidelines and restrictions. Don’t congregate in bars. Don’t forget to wear a mask.

Fauci makes all that clear to the vice president in the task force meetings these days. He doesn’t make it clear to the president — because he can’t. “You don’t ask to see the president. The president will ask you to see him when he wants you to see him,” says Fauci, who with six presidents’ worth of experience ought to know. Even when relations with Trump were good, they were still arms-length at best. Early on, at the end of the task force meetings, some members would go to the Oval Office and brief Trump and then would come to those news conferences. “Well,” Fauci says, “as you probably have noticed, that has not only tapered off but essentially stopped.”

So as the cases mount, and the death rates climb, and the gains of the spring are sacrificed to the needs of an election-year calendar, science has taken a far back seat to politics. Every time the president opens his mouth to contradict what the experts say or to invent something that the experts deny, he turns fact into belief — and tears at the truce that has held for so many years. And now that such talk has become commonplace, even acceptable, a much bigger battle between fact and ignorance is probably inevitable, with all the uncharted hostility and all the casualties you might expect.

The unbridled acrimony matters for science. “There’s so much extremism in things right now, it makes it very difficult,” says Fauci. “Whenever you want to be completely transparent about science and what it means, you have people who almost take that as an affront against them.”

Because an artless President Trump can’t hold up his end of the deal, the peace that Fauci so carefully crafted beginning with the AIDS crisis might not survive this generation’s epidemic — even if Fauci himself does. And when the next era’s war between science and politics arrives, and Americans ask some version of the age-old question, “Where’s Fauci?” the answer will be nowhere. Another Tony Fauci will never exist.

Read more:

Larry Hogan: I’m a GOP governor. Why didn’t Trump help my state with coronavirus testing?

Molly Roberts: This is how you lose a culture war

The Post’s View: We don’t worry for Dr. Fauci. We worry for the country.

Greg Sargent: Trump’s rage at Fauci just boomeranged back on him

Watch: Trump vs. the coronavirus