John Lewis practiced what he preached. We are a better nation for it.

The historic life of Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) started when the 17-year-old from Troy, Ala., sent a handwritten letter to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Dr. King, I need your help,” Lewis told me he wrote. “I want to attend this little college, Troy State College, it’s only 10 miles from my home. I submitted my application, my high school transcript. Can you help me?”

In response, Lewis said during an interview in Atlanta in 2018, King sent Lewis a round-trip bus ticket to Montgomery, Ala. Upon seeing the young man before him, looking “fresh, clean, sharp” in an “inexpensive suit,” King asked, “Are you the boy from Troy? Are you John Lewis?”

“‘Dr. King, I am John Robert Lewis.’ I gave my whole name — but he still called me the boy from Troy,” recounted Lewis. Also there was Ralph Abernathy, who was King’s best friend and fellow civil rights leader. “To be candid, I was scared. I was nervous,” Lewis continued. “To be standing in the presence of these two unbelievable leaders of this movement that I’d read about … and I knew that I was like a small, frightened child in the midst of greatness.” That frightened teenager would grow up to be a great civil rights leader in his own right.

[For John Lewis, meeting Martin Luther King meant getting into ‘good trouble’]

Lewis was elected to Congress in 1986 and became known as the “conscience of the Congress.” He was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2010. He continued to make “good trouble” until the day he could no more. That day came late Friday night when Lewis passed away after battling pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old.

Lewis participated in sit-ins to integrate lunch counters in 1960. He was part of the Freedom Rides to integrate interstate travel in 1961. And as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), not only was he one of the “Big Six” leaders to organize the historic 1963 March on Washington, Lewis was also its youngest speaker. Today, none of the speakers survive.

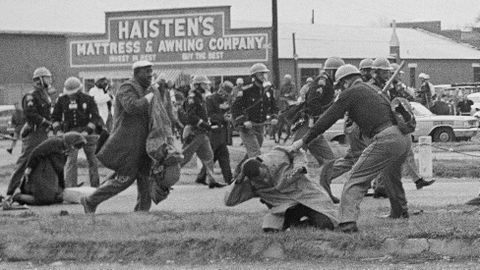

In this March 7, 1965, file photo, a state trooper swings a billy club at John Lewis, right foreground, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, to break up a civil rights voting march in Selma, Ala. (AP Photo/File)

In this March 7, 1965, file photo, a state trooper swings a billy club at John Lewis, right foreground, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, to break up a civil rights voting march in Selma, Ala. (AP Photo/File) If Americans watching the March on Washington didn’t know the young man standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial imploring his nation to “Wake up,” they would never forget him after “Bloody Sunday.” On March 7, 1965, Lewis was among the leaders of a voting rights march from Selma, Ala., to the state capitol in Montgomery. As the protesters crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Alabama law enforcement met them on the other side. Clad in a trench coat and a backpack, Lewis stood as the state troopers advanced. The marchers were beaten with nightsticks and tear gassed until they retreated over that bridge. Lewis was hit so hard in the head he got a concussion and a fractured skull.

[Walking the Edmund Pettus Bridge with John Lewis]

“I thought I was going to die. And to this day, I don’t know how I made it back across that bridge to the streets of Selma,” he told me. The world saw what happened to the marchers later that night on television, and the collective horror turned to action. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 became law five months later.

One of the greatest honors of my life was to walk the Edmund Pettus Bridge with Lewis as part of the annual Faith and Politics Institute’s civil rights pilgrimage in commemoration of “Bloody Sunday” — not once, but four times. The routine was the same. A slow procession to the top of the bridge with Lewis and others who were there that day. The stories were the same. The songs were the same. The mood was the same, at once somber and celebratory as we stood enveloped in history and surrounded by some of the people who made it.

The emotions can be overwhelming. The first time I went in 2017, tears fell from my eyes as I looked to the other side of the bridge where Lewis and others were beaten. During last year’s pilgrimage, Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-Del.) let out an audible wail as “Come by Here, Lord” was sung. This year, tears quietly flowed all around. Everyone seemingly moved by the same realization: This might be the last time we would be with the great man on that sacred spot.

From left: Rep Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-Del.) is comforted by Rep. Deb Haaland (D-N.M.) and Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Tex) on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on March 2, 2019. (Jonathan Capehart/The Washington Post)

From left: Rep Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-Del.) is comforted by Rep. Deb Haaland (D-N.M.) and Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Tex) on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on March 2, 2019. (Jonathan Capehart/The Washington Post)  Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) looks out over Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington on June 7. He died in Atlanta, on Friday. (Jonathan Capehart/The Washington Post) (TWP)

Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) looks out over Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington on June 7. He died in Atlanta, on Friday. (Jonathan Capehart/The Washington Post) (TWP) I was further honored to witness one of Lewis’s last public outings, at the newly designated Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington at 6:35 a.m. on June 7. Sporting a black-and-white mask, gray trousers, white shirt and blue zip-front sweater, he looked “fresh, clean, sharp.” Atop a building overlooking the plaza, Lewis stepped onto a makeshift platform to get a better view of the bold yellow letters stretching toward the White House.

As Lewis focused his attention on the scene below, I focused my attention on him. I was looking at a man whose legacy was forged nearly 60 years ago. A man who was gazing upon public art that signaled that his pursuit was nowhere near finished. A man who was “deeply moved and inspired” by the nationwide protests in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd.

In my last interview with Lewis last month, I asked him what advice he had for this generation of marchers, who will invariably face setbacks. “You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more,” he said. “We must use our time and our space on this little planet that we call Earth to make a lasting contribution, to leave it a little better than we found it.”

Lewis led a life of humility and sacrifice. He married lofty language about who we should be as a nation with concrete action to try to make it so, including speaking out against discrimination against LGBT Americans. His words and deeds over the course of his life made my life as an openly gay African American man possible today. Because Lewis practiced what he preached, we are a better nation. Rest in peace, John Robert Lewis. Thank you for a lifetime of good trouble.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter: @Capehartj. Subscribe to Cape Up, Jonathan Capehart’s weekly podcast

More from Jonathan Capehart:

How Martin Luther King got John Lewis into ‘good trouble, necessary trouble’

John Lewis is ‘Happy’ and it’s wonderful.

‘I just felt like something had died in all of us’: John Lewis on the death of Martin Luther King

PODCAST: Voices of the Movement: Stories from civil rights leaders who changed America

More on John Lewis:

Colbert I. King: John Lewis will always be with us

David Greenberg:‘Invictus’ was among John Lewis’s favorite poems. It captures his indomitable spirit.

John R. Lewis, front-line civil rights leader and eminence of Capitol Hill, dies at 80