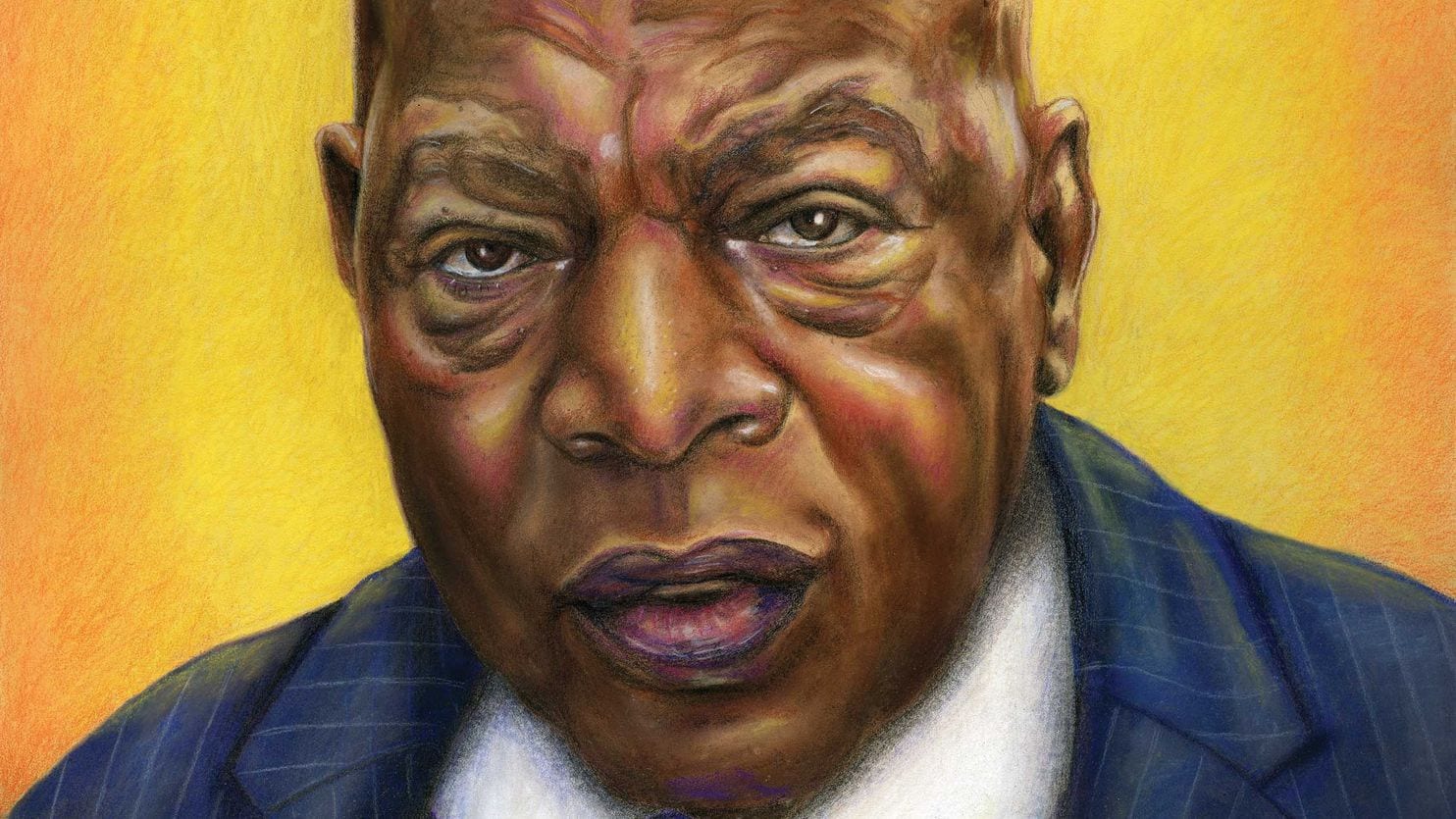

John Lewis will always be with us

John Lewis will always be with us. How on earth could we ever be separated?

John Lewis is in America’s DNA. He is a fundamental and inseparable part of the nation’s ongoing quest to heal historical racial wrongs and present-day woundings.

John Lewis’s DNA is embedded in civil and human rights groups fighting for social justice across the country. It was found present in Minneapolis, and Louisville, in Atlanta and Brunswick, Ga., where police and vigilante violence was inflicted upon unarmed black citizens.

Just as DNA contains the instructions needed for an organism to develop and survive, Lewis’s life story contains the directives to follow in the struggle to make America a better country.

[John Lewis to Black Lives Matter protesters: ‘Give until you cannot give any more’]

John Lewis gone? Impossible. As long as the vestiges of slavery and Jim Crow linger, as long as African Americans and people of color continue to suffer from the damages and losses growing out of racism and deprivation, his living legacy is with us. Because he has given us what is lasting.

He never swerved from his credo that “people of all faiths, and no faiths, and all backgrounds, creeds, and colors” must band together, “to fight for equality and justice in a peace, orderly, nonviolent fashion.” It was a statement he repeated as recently as a few weeks ago following the police killings and unrest in his Atlanta hometown and across the nation.

“I see you, and I hear you. I know your pain, your rage, your sense of despair and hopelessness.”

Like the pain he took for us on March 7, 1965, in Alabama when after leading marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, state troopers viciously attacked, fracturing his skull.

[Voices of the Movement podcast: John Lewis and Andrew Young tell the story of Bloody Sunday in Selma]

But rioting, burning and looting is not the way, he said. His instruction — good then, invaluable now — “Organize. Demonstrate. Sit-in. Stand-up. Vote. Be constructive, not destructive.”

John Lewis was always thus.

Troy, Ala., was his place of birth in 1940, and his home until 1957, when he left for the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville. That’s where the seeds of civil rights were planted. And they sprouted in lunch counter sit-ins, campus protests, Freedom Rides and arrests. Loads of arrests, more than 40, recalled Lewis.

It was also during the time when student Lewis met the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who called him, “The boy from Troy.”

The boy from Troy was a giant of a man, though, at first blush, he had the trappings of a bantam rooster. Small bird, big attitude. He was short in statue, true. But no Napoleon complex. Just a gargantuan commitment to fighting injustice and inhumanity whenever and wherever found.

His voice, redolent with the richness of the Civil Rights movement, was heard at the Lincoln Memorial in the March on Washington, and during the historic and game-changing march from Selma to Montgomery that he helped to organize. His orations for social justice shook the rafters in the halls of Congress.

Just as he stirred the crowd of journalists at the Poynter Institute’s Pulitzer Prize Centennial main event at the Palladium Theater in St. Petersburg, Fla., on March 31, 2016.

My son Rob King of ESPN and I were co-participants in “The Voices of Social Justice and Equality” program, where Lewis delivered his keynote address. Oddly enough, with all the gatherings in Washington where Lewis was present over the years, St. Petersburg was the first time I had the chance to personally interact with him.

As always with a John Lewis speech, nothing was left in the tank.

“I come here tonight to thank members of this great institution for finding a way to get in the way,” Lewis told us. “Finding a way to get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble” is what journalists should be doing, he said.

“We need the press” he said, “to be a headlight and not a taillight.”

With great passion, Lewis left us with these words: “You must not give up. You must hold on. Tell the truth. Report the truth. Disturb the order of things. Find a way to get in the way and make a little noise with your pens, your pencils, your cameras.”

And there is John Lewis away from the camera’s eye.

Dennis Marley, who lives in Atlanta and has a place in the New Orleans’ French Quarter, wrote in an email following my July 4 column: “In July 2013, I attended the funeral of Congresswoman and Ambassador Lindy Boggs. In the Plaza in front of the Cathedral, I waited patiently for an opportunity to greet Congressman John Lewis. I waited my turn to say hello and introduce myself: ‘my name is Dennis Marley, I live in Atlanta Sir; it is my honor to meet you’. With his firm handshake he looked me in the eyes and said: ‘how can I help you Mr. Marley?’”

Separated from that paragon of public service? Never.

Read more:

David Greenberg:‘Invictus’ was among John Lewis’s favorite poems. It captures his indomitable spirit.

Michele L. Norris: A running giant passes the baton

The Post’s View: How John Lewis caught the conscience of the nation

Jonathan Capehart: John Lewis practiced what he preached. We are a better nation for it.

John R. Lewis, front-line civil rights leader and eminence of Capitol Hill, dies at 80