Baseball’s back, but the questions won’t end, and the answers won’t get easier

Beloved virologist Anthony S. Fauci, who long has said that a short MLB season was plausible, threw out the worst ceremonial first pitch since John Wall. Hey, the dude just doesn’t want anyone catching anything.

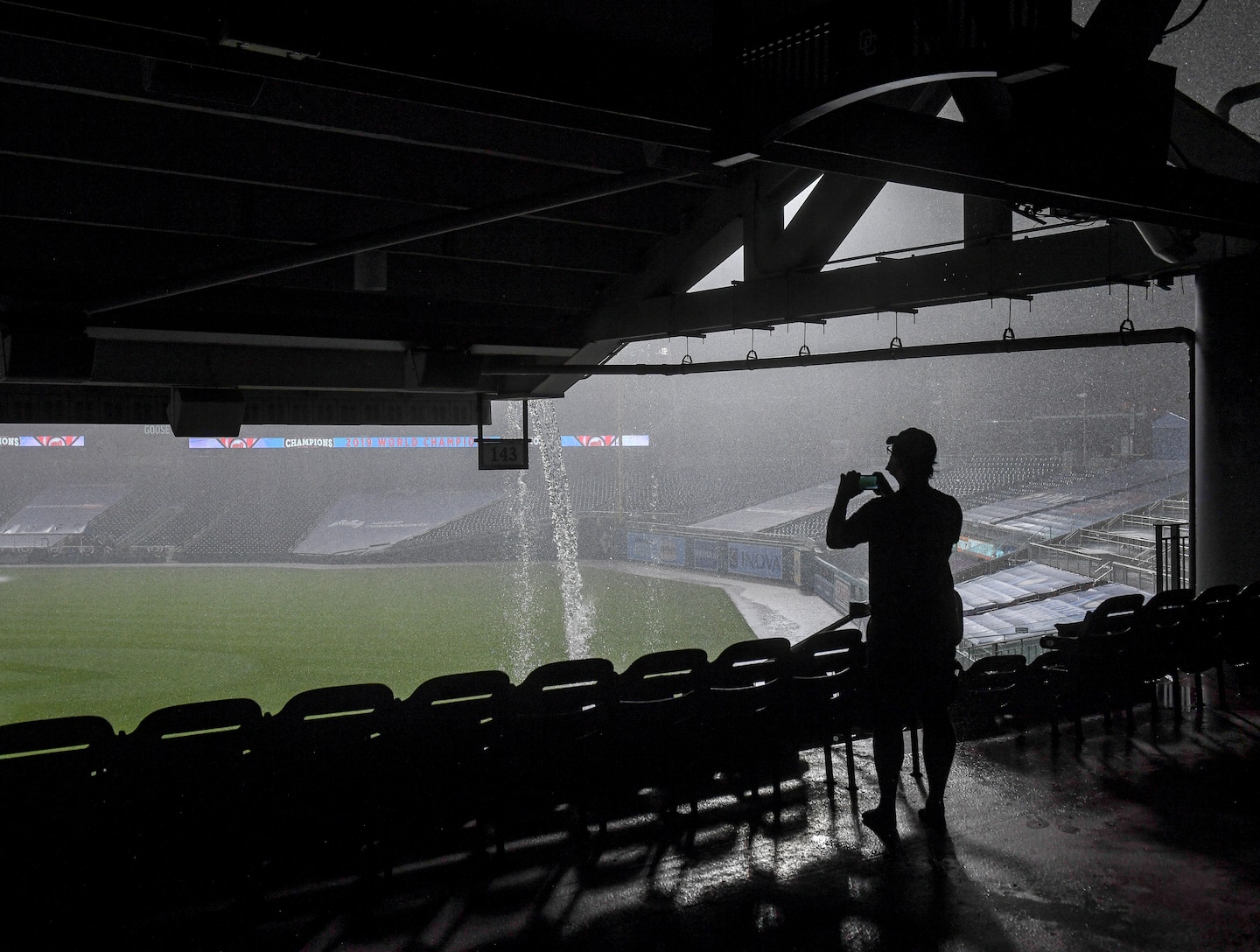

Then the end-of-days lightning storm that seems to interrupt 96 percent of Nationals Park games ended the official contest in the sixth inning. What a face-slap.

Thanks, we (probably) needed that.

By Friday, the Atlanta Braves sent two catchers home after they showed symptoms but tested negative. More toppling trees, maybe the same cause.

After months of preparations, negotiations and elaborate testing protocols, MLB and its fans, including me, have built up a significant investment — financial or emotional — in trying to play a mini-season. The culture of every sport, top to bottom, is “hang tough” and “give our decisions time to play out.”

Stubborn, almost defiant patience is an MLB virtue, exemplified by last season’s Nationals. But maybe not this time.

Within days, the NBA, in its Florida bubble, and the NHL, sequestered in Canada — a unified, science-led country that had four coronavirus deaths Thursday (the United States had 1,078) — will try to pull off similar season-saving high-wire acts to crown their champs and make millions.

Long before the NFL can imagine a regular season snap, these sports will have their judgment and character tested in ways they have never experienced and for stakes, even life and death, that can do them more damage than they have ever imagined possible.

The sight of MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred, who has spent his life in baseball’s complex but obscure innards, on national TV was disconcerting on multiple levels.

As lightning struck behind him, he hyped the game’s shameful, stupid new gimmick: a 16-team, make-a-buck playoff system, created this week. It will maximize two things: October TV revenue and the odds that the game’s best teams — say the Yankees and the Los Angeles Dodgers — get knocked out in a mockery of a three-game first-round series.

If Manfred’s judgment is this bad or if he is this pliant to the money lust of his bosses, then what chance is there that he will have the backbone or the leadership skills to shut down this season if needed?

But how can you tell when that is “needed”? Few U.S. leaders have had a clue when this virus is about to go from a whisper to a roar. In 2020, when in doubt, declare a small defeat and be glad you did. Because you can always lose a lot more if you wait.

You feel the full medical and moral drama unfolding now in sports only if you do not view it through our current rabid open-up vs. shutdown political fight.

Ironically, sports fans may be well positioned to grasp this nonpartisan ambiguity because they feel both sides intensely: open my sport but protect every player and every team trainer in the game. That’s the conflicted position that will torment decision-makers.

For example, those who run baseball, as well as the players themselves, sense every reason bringing back the game carefully will be a joy to the public, an economic crutch for a limping industry and even an example of a complicated business resuming its work. (Now choose up sides on all those “tests” teams use.)

On the other hand, the urgency, almost the desperation, to return feels like a microcosm of our national infantilism when faced with the need for self-discipline and deferred or denied gratification.

Trying to play baseball in a pandemic is not as dumb or selfish as millions saying, “I want to party at the beach just like every year.” Or government leaders, at many levels, allowing or encouraging mass unmasking. But there are scary similarities.

MLB plans just a 66-day season. Why can’t you spot a coronavirus outbreak on one of two teams quickly enough to trace and thwart it? That’s like the flawed thinking of many states in June. In 33 days, Florida shot from 1,096 daily cases to 15,300.

The scary core of MLB’s predicament — and soon the NBA’s and NHL’s, too — is: Playing our sport is what we do, who we are and how we make our money. We’re going to try to do it until the virus stops us.

From all over the world we’re learning the lesson that this is a terrible basic assumption. You get ahead of this virus before it even looks like a problem, or it ends up crushing you. South Korea, Japan, Australia, Canada and Germany, with a combined population of 325 million (the United States has 330 million) had 15 deaths Thursday. Arizona, with 7.2 million, had 89 dead.

You don’t measure disaster for a country — with refrigerator trucks lined up with corpses — the same way you measure it for a pro sport. But how do you measure it for a sport? I don’t know.

If we had that time machine for sports restart hindsight, most people probably would agree instantly on “that was worth the risk” or “what an utter disaster.” But we don’t. And this decision dwarfs others in sports.

League bosses, who are not at risk, and athletes, who think they are invulnerable, are both going to be tempted — to keep playing chicken with the virus until it makes them stop.

As most of the world already knows, by then it is usually disastrously too late.

MLB, the NBA and the NHL are all about to face tough but unique-to-their-sport choices. There are good reasons to try to play and one obvious reason to stop. When trying to sail through a pandemic perfect storm, maybe one simple rule of thumb could help.

If you think, “Maybe, given what we are seeing so far, we should cancel the rest of this season,” then you already have your answer.

Faced with the coronavirus, quickly remove the “maybe.”