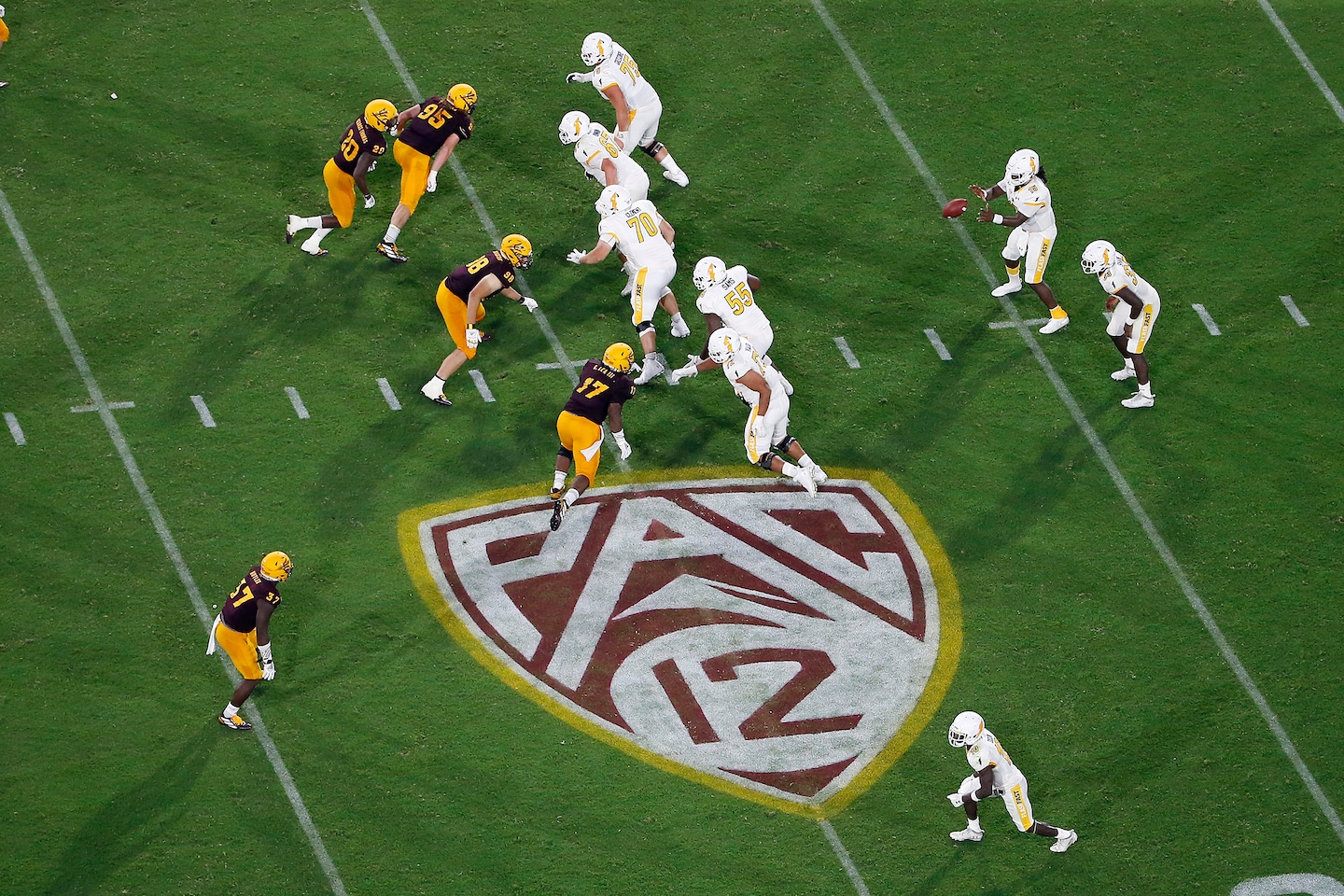

Pac-12 football players threaten boycott if health and social justice demands are not met

The Pac-12 players asked for the conference to enforce safety standards as teams return to play amid the novel coronavirus pandemic. After the death of George Floyd and a summer of unrest, the players want the Pac-12 to commit to addressing social issues such as racial injustice and grant players more economic freedom through revenue sharing and the ability to profit off their names, images and likenesses.

More than 400 Pac-12 players were part of the GroupMe chat where conversations about this movement took place, organizers said, but it is unknown how many players would opt out of the season if the demands are not met.

As unpaid college athletes continue to grasp the leverage they wield in this multibillion-dollar industry, they have started to push for more rights and protections. Particularly now as the season nears with the number of coronavirus cases still rising in parts of the country, many college football players have voiced concerns about the risks of playing and doubts that the NCAA will value their safety over revenue.

The National College Players Association and the organization’s executive director, Ramogi Huma, offered guidance to this Pac-12 player-led movement. Huma said the Floyd protests, which saw numerous college athletes raise their voices against police brutality in recent months, and the coronavirus pandemic combined to create the impetus for a rebellion unlike any in college football history.

“Business as usual in college sports is very abusive,” Huma said. “That combined with a pandemic is a total disaster. NCAA sports has failed. And with players, I think there’s just some desperation. They’re really concerned about their health and safety.”

When California at Berkeley players Valentino Daltoso and Jake Curhan spoke with Huma about their concerns returning to campus to play football during a pandemic, Huma directed them to Andrew Cooper, a graduate student and member of Cal’s cross-country team. Cooper helped compose a letter to the NCAA this year urging it to forgive a year of eligibility for athletes who had lost their spring seasons because of the pandemic, and he became part of the discussions that resulted in Sunday’s statement.

Initially, the three Cal athletes spoke about covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, but the discussions quickly became more wide-ranging. They saw college athletes who wanted to play a role in the conversations and protests about racial injustice. Within the athletic department, Cooper said, the financial divide between millionaire coaches and unpaid athletes was painfully stark.

“We realized that all of the issues — racial injustice, covid-19 and economic justice — were the same thing, and we wanted to think about a blueprint to address what college sports might look like,” Cooper said.

Athletes from across the Pac-12 collaborated in a GroupMe chat that began a month ago with just a dozen players. It allowed them to connect with one another through social media and organize.

“We didn’t really know exactly what we wanted to get out of this,” said Cody Shear, an offensive lineman at Arizona State. “But we knew that we had the same morals and that we wanted to make a statement on behalf of the college football players.”

The players’ demands include a reduction of excessive spending on facilities and the salaries of coaches and conference leaders. The players want the Pac-12 to address racial injustice by forming a civic-engagement task force and a Pac-12 Black college athlete summit. They ask that 2 percent of conference revenue go toward financial aid for low-income Black students and other community initiatives.

The athletes are seeking medical insurance for sports-related conditions, including those that result from the coronavirus, that lasts six years after the end of their college eligibility. The players want the conference to distribute 50 percent of its revenue generated by each sport to the athletes. Huma noted this would not lead to any Title IX issues because the Pac-12 is a private entity.

The Pac-12 Conference has yet to hear from the group about these demands and said in a statement: “We support our student-athletes using their voice, and have regular communications with our student-athletes at many different levels on a range of topics. As we have clearly stated with respect to our fall competition plans, we are, and always will be, directed by medical experts, with the health, safety and well being of our student athletes, coaches and staff always the first priority.”

Ricky Volante, the chief executive and co-founder of the Professional Collegiate League, which wants to become an alternative to the NCAA, said his organization consulted with individual players, including Stanford cornerback Treyjohn Butler, and offered input.

Volante said players in larger numbers than ever before are coming to terms with what he described as a power imbalance. Volante said he didn’t believe the conference would ask the commissioner, administrators or coaches to take a pay cut or give up bonuses, describing those demands as “incredibly naive.” He suggested the Pac-12 may postpone the season until the spring as a challenge to the players who organized the group.

“That would take the sting out of what happened,” Volante said. “They would essentially be daring the athletes to stay lockstep on their demands for the next six months.”

If the conference responded by punting the college football season to spring, effectively challenging players to stay resolved for six months while the pandemic presumably abated, Huma said, the players would rise to that challenge. The past few months have reminded these athletes of their power, and the pandemic has highlighted the importance of voicing their concerns.

“You have college football players, most of whom are players of color, really being put on the front lines in a football season to make money that they’ll never see, without even proper protections,” Huma said. “They want to play, but they want to play in an environment where everything is being done to keep them as safe as possible and where they’re treated fairly.”

Read more: