These neighbors were hospitalized with coronavirus. Their vastly different journeys show the depths of Brazil’s rich-poor divide.

RIO DE JANEIRO — Two men were going to the hospital, unsure of whether they’d return. It was April, when Brazil’s worst fears about the novel coronavirus were beginning to be realized. The disease had started to kill all over the country. Now it had come for them, too.

Tiago Lemos knew his lungs were shot.

Rodrigo Guedes could no longer stand.

The coronavirus has played a game of Roulette across the world: Who lives? Who dies? In most countries, a familiar set of variables — age, sex, preexisting conditions — has helped make at least some sense of the confounding disease. But in Brazil, one of the most unequal countries in the world, another crucial deciding factor has been class. The poor are dying at a much higher rate than the wealthy.

In Rio de Janeiro, the rich and poor live on top of each other. Hillside favelas tumble down to oceanfront condominiums. Maids sleep in the homes of their employers. People of all classes come together at the beach. But despite the proximity and intimacy between the classes, two people who are the same in every other way — age, sex, health, city — can end up having completely different experiences with the virus.

One goes into the private health system, which can rival any in the developed world. The other heads into the public health system, where shortages in equipment and personnel can mean the difference between life and death.

A view of Rocinha, Brazil’s largest favela, in Rio de Janeiro. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post)

A view of Rocinha, Brazil’s largest favela, in Rio de Janeiro. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post) The story of the two systems — and two Brazils — was the story of Lemos and Guedes. They were roughly the same age: Lemos is 37, Guedes, 38. They lived in neighboring communities in Rio de Janeiro. They grew into adulthood in a Brazil that was ascendant, where a better life was there for the taking. Each of them had seized it, rising above the conditions into which they were born.

But there were key differences.

Lemos has private health insurance. Guedes doesn’t.

Lemos, a physician, lives in the wealthy community of Barra da Tijuca, where President Jair Bolsonaro also maintains his home residence. Guedes has spent his life in nearby Rocinha, the largest favela in Brazil, where he owns an optical shop.

When the virus came to Rio, their lives collapsed around a shared experience: Each man in the prime of his life, neither with preexisting conditions, being taken to the hospital as his lungs failed.

One entered the private medical system. The other, the public system. And from there, their lives diverged, once more.

A devastating outbreak, distributed unevenly

A waiter in a protective mask and visor clears a table on the beach of Barra da Tijuca in Rio. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post)

A waiter in a protective mask and visor clears a table on the beach of Barra da Tijuca in Rio. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post) Months into the world’s second-worst outbreak, the coronavirus has become one more metric to measure inequality in Brazil. The coronavirus has reached 98 percent of cities and infected more than 3 million people. On Saturday, the official death toll passed 100,000.

But the destruction has not been distributed equally. Among intensive care patients, people without education have been three times more likely to die than those with college degrees, researchers found. The rate of transmission has been three times greater in poor neighborhoods than wealthy ones. Black patients are at greater risk than Whites.

[As coronavirus kills indigenous people in the Amazon, Brazil’s government goes missing]

When explaining these discrepancies, researchers have pointed to differences in health and living conditions. The poor tend to live in dense slums, grapple with more infectious diseases and die a decade earlier, on average, than the wealthy. But others have highlighted the failures in the public health-care system.

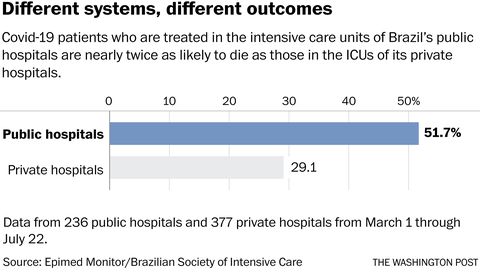

That system has been hailed as a marvel in the developing world, serving more than 150 million Brazilians. But despite its size and resources, it has failed to keep pace with the coronavirus. As its hospitals reached capacity, the mortality rate among intensive-care coronavirus patients exceeded 50 percent, according to the Brazilian Society of Intensive Care. In the private system, the rate was 29 percent.

Problems that plagued it before the pandemic — inefficiency, corruption and insufficient capacity — have been magnified during it. Disorganization and bureaucracy have left the health ministry unable to spend the money it’s had on hand. Even as the virus maimed the country, the ministry deployed only a third of its coronavirus budget.

“The Brazilian health ministry never prepared itself,” said Miguel Nicolelis, a prominent physician and scientist tracking the outbreak here. “By the time it hit Brazil, it didn’t have enough professional equipment, masks and — to our surprise and shock — enough basic medicine.”

The fallout has been particularly acute in Rio de Janeiro, where plans to expand the public system were undone by incompetence and corruption, the line of coronavirus patients awaiting treatment reached nearly 1,000 people — and where Rodrigo Guedes was returning home one day when he started to cough.

A uniquely vulnerable community

Rodrigo Guedes da Silva, 38, drinks coffee at home in Rocinha before leaving for his small shop in the favela. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post)

Rodrigo Guedes da Silva, 38, drinks coffee at home in Rocinha before leaving for his small shop in the favela. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post) Growing up, Guedes thought little about class. He was poor, that much was clear. Living at the top of Rocinha, with its view of the luxury buildings far below, he had a sharp understanding of what he had and what he didn’t.

He says he never begrudged the wealthy, not when he saw those buildings, nor when he washed their cars or sold them snacks. Everything he’d ever wanted — his family, an open view of sea and mountains — was in the favela, and he swore he’d never leave.

Even after gangs seized control, and the police started killing more people, it remained home, where he and his wife, Jailma, wanted to raise their daughter and open a small shop selling eyeglasses.

He never anticipated the coronavirus. Or that everything about Rocinha — its poorly ventilated passageways, its unreliable water system, its residents who had to keep working to survive — would make it an explosive breeding ground. One-fourth of its residents would contract the disease.

Guedes opens his optical shop. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post)

Guedes opens his optical shop. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post) The first symptom was a cough. Then body pain, fever and exhaustion. He went to a clinic, but the doctor said it was nothing and sent him home. Jailma couldn’t believe it. She was watching this heavily muscled man wither to nothing. He could barely stand beneath the shower head long enough to get wet. She made him go to another clinician, who said it wasn’t nothing — it was covid-19. His lungs had been chewed up by the disease.

The public hospital was overrun with patients. “It’s going to be okay,” Jailma said, but Guedes wasn’t sure. For one of the first times in his life, he says, he experienced a pang of class envy. He no longer felt like the upwardly mobile businessman, but once more the poor kid selling snacks on the beach, invisible to everyone.

‘Never so wrong in my life’

Tiago Lemos and his wife, Juliana, both physicians, at home after work in Barra da Tijuca. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post)

Tiago Lemos and his wife, Juliana, both physicians, at home after work in Barra da Tijuca. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post) Tiago Lemos strode through a private hospital in west Rio, feeling uncertain. He’d spent weeks reading medical journals and health guidelines. He’d worked the H1N1 pandemic. He felt ready.

But this disease was unlike any he’d known. How subtly it took hold, how suddenly it killed, how unpredictable its selection of victims.

Lemos did everything he could to protect himself, but he believed infection was inevitable. Still, the odds were on his side — he was young and healthy — and when it did come, he felt almost relieved. He could get it out of the way and get on with his life. But when his cough didn’t improve, and he didn’t bounce back, he realized how foolish he had been.

“Never so wrong in my life,” he said.

[In Brazil, a dying man and a desperate search for an open bed]

He’d always believed in the cool application of logic and reason. The son of a small-business owner and civil servant, he’d grown up middle class, playing beach soccer with the children of doormen and janitors. He rose above his station by using his intellect to think through complex problems. But this was one he couldn’t figure out.

“I’m going to die,” he told his wife, Juliana.

“It’s going to be okay,” she said. “This will pass.”

But he understood the coronavirus in a way she didn’t. His insurance plan was one of the most comprehensive in Brazil, and it would help him get the best care available. But it might not be enough. He thought of a family he knew, all infected. The parents had gone into the private system, where he treated them. The son went into the public system. All had died.

‘I’m fighting for my life’

Guedes spent days in a hospital that was so short of staff he ended up feeding and tending to other coronavirus patients himself. (Courtesy of Rodrigo Guedes)

Guedes spent days in a hospital that was so short of staff he ended up feeding and tending to other coronavirus patients himself. (Courtesy of Rodrigo Guedes) Guedes couldn’t bring himself to tell Jailma everything. He’d seen her desperation when they arrived at the emergency health clinic CER Leblon. No one came to check on him. She had to fetch his wheelchair herself. She began to shout: “My husband can’t breathe, and no one is helping us!”

The center was in disarray. Health inspectors found it had no pandemic contingency plan. No surgical masks for patients. Insufficient gloves, masks and disinfectant. The Rio de Janeiro Nursing Council said it had de-prioritized the care of patients to protect its staff.

“Nobody believed the potential of the virus,” said Ana Teresa Ferreira de Souza, a contributor to the report. “Isolation wasn’t happening.”

Health officials who oversee the clinic say equipment shortages have hobbled medical systems everywhere. Brazil was “an example of what has happened all over the world,” they said in a statement.

There were no beds for Guedes, so he was rolled into a hallway. It was filled with patients, all struggling for breath. There was only one oxygen catheter, so they took turns: One person would breathe for a minute or two, then pass it on. Nine hours passed that way — five minutes of oxygen every half-hour — before he was taken upstairs to a room stuffed with patients.

He reached for the oxygen catheter beneath his bed and found it was broken.

“I’m fighting for my life,” he messaged Jailma.

Jailma, pacing back home, hounded the hospital with phone calls. She was told his condition had deteriorated. That night would decide whether he lived or died.

Too weak to say goodbye

Lemos thought it might have been easier if he weren’t a physician. He wouldn’t have known how quickly he was failing. Next would come intubation, then the ventilator and a plummeting chance of survival.

Anxious in his private room at CopaStar — which compares itself in promotional materials to a five-star hotel — he placed video calls to Juliana and his doctors. They almost always answered.

His lead physician, Rafael Pottes, hoped to envelop him in “multi-professional treatment.” The hospital administered a battery of medications — corticoid, azithromycin, chloroquine — and physical therapies, and checked on him frequently.

[Coronavirus collides with Latin America’s maid culture — with sometimes deadly results]

Pottes knew one of the most important components in treatment of coronavirus patients was mental care. “The fear of the unknown, of a disease that had been killing so many people in the world,” Pottes said. “He almost had a panic attack as he got sicker.”

Pottes asked Juliana to come to the hospital, hoping she might calm him. When she arrived, her hopes for a quick recovery vanished. Lemos was disoriented, on an oxygen tank and barely able to communicate. If he got any worse, the doctors warned, they’d intubate him.

Lemos thought it might be the last time he’d see his wife. But he couldn’t marshal the strength to speak.

‘It was, sincerely, humanly impossible’

After six days at the clinic, slipping in and out of consciousness, Guedes stabilized and was transferred to another hospital. Now he was in a room with four other patients, all in worse shape. He watched as one begged for food left just beyond his reach.

If anyone needed help, the nurses said, he simply had to shout. But no matter how much he called, nobody appeared. Hours went by without anyone entering. After days feeling like a “dog abandoned in the road,” he understood: The nurses, short on protective equipment, were scared. Sometimes one would rush in with food, set it down and scamper away — without making sure the patient could reach it.

[Brazil’s favelas, neglected by the government, organize their own coronavirus fight]

“This happens a lot,” said Alexandre Telles, a physician at the hospital. “There are patients who develop hypoglycemia because they aren’t fed well.” So many workers had been infected that basic services were being neglected: “It was, sincerely, humanly impossible.”

Guedes looked at the patient, unsure if he had the strength to help.

He rose and wobbled over. He dragged the man’s table closer to his bed. He pulled the top off the food. He sprinkled on some salt. Then Guedes asked him what he would like to eat first.

He knew the disease would devastate Brazil

Brazilians enjoy the beach in Barra da Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, on July 27. The country is suffering the second-worst outbreak of the coronavirus in the world, after the United States. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post)

Brazilians enjoy the beach in Barra da Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, on July 27. The country is suffering the second-worst outbreak of the coronavirus in the world, after the United States. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post) And then the illness lifted. Lemos could breathe easier. His strength returned. He couldn’t say what happened — why he survived, when others haven’t.

On the day he was released from the hospital, he asked his wife to drive him down to the beach. He looked out the car window. It looked the same as always: Filled with people drinking, people without masks, people enjoying another beautiful day in Rio.

[While other countries look to open up, Brazil can’t find a way to shut down]

He knew the disease would devastate Brazil. The news would continue to be nightmarish — public hospitals failing, ambulances with nowhere to take patients, equipment shortages, the dead piling up in the tens of thousands.

Lemos had to get back to work.

All of this might have been different

Guedes, who has recovered from the coronavirus, goes back to work. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post)

Guedes, who has recovered from the coronavirus, goes back to work. (Maria Magdalena Arrellaga for The Washington Post) Guedes spent 11 days in the hospital. He passed much of the time flipping through his phone, seeing images of the hospitals treating the rich and famous. “Everything was so beautiful,” he said. “Not at all what we were going through.”

He eventually recovered. But for weeks afterward, Jailma would suffer anxiety — unable to read news about the coronavirus, reaching out in the night to check his breathing. All of this might have been different, Guedes believed, if he’d gone to a private hospital.

He returned to Rocinha, embraced his daughter, reopened his shop. He trekked to the top of the hill, to the house where he was raised, where his mother still lived. He stared out into that familiar view, where sky and sea became one, and where the sprawl of the favela collided with luxury below.

Photo editing by Chloe Coleman. Video editing by Alexa Juliana Ard. Design by Brandon Ferrill. Copy editing by Briana R. Ellison.