The pandemic has forced Haila, Jingchu and many other Chinese students to rethink dreams of a U.S. diploma

Through days of schooling and nights of studying, the two Chinese students pictured the big moment: Telling their parents. Posting the news. Haila Amin off to the University of Virginia. Jingchu Lin on route to Yale.

It would be a personal triumph and a turning point. A chance to chart a new course in a new country. That was what they worked for. That was the plan.

But between the time they applied to U.S. schools and decision day in the spring, a virus changed the world around them, upending nearly everything.

For Haila, Jingchu and other Chinese students bound for the United States, fall 2020 looks nothing like what they expected. Some returning students are stranded in the United States. Incoming students are stuck in China. Nobody knows what will happen in September. Nobody can believe this is happening at all.

That uncertainty is changing lives and trajectories. It will reshape American education, potentially making U.S. institutions less attractive. And it may diminish what remains of the United States’ soft power in China as ties between the world’s two largest economies hit fresh lows.

Chinese students have much on the line: Years of work, family sacrifice, the chance to study in an environment where they can for the most part browse, speak and write as they please.

U.S. schools do, too. For more than a decade, Chinese students have been one of the biggest stories in American higher education. Between 2009 and 2019 Chinese students in the United States nearly tripled, according to data from the Institute for International Education.

There were more than 360,000 Chinese students in the United States in the 2018-2019 academic year, making up about a third of international students, the IIE reported. According to a Department of Commerce estimate, these students put $15 billion into the U.S. economy in 2018.

Even before the coronavirus hit, there were signs of a slowdown. After years of double-digit growth, new Chinese student enrollment is leveling off.

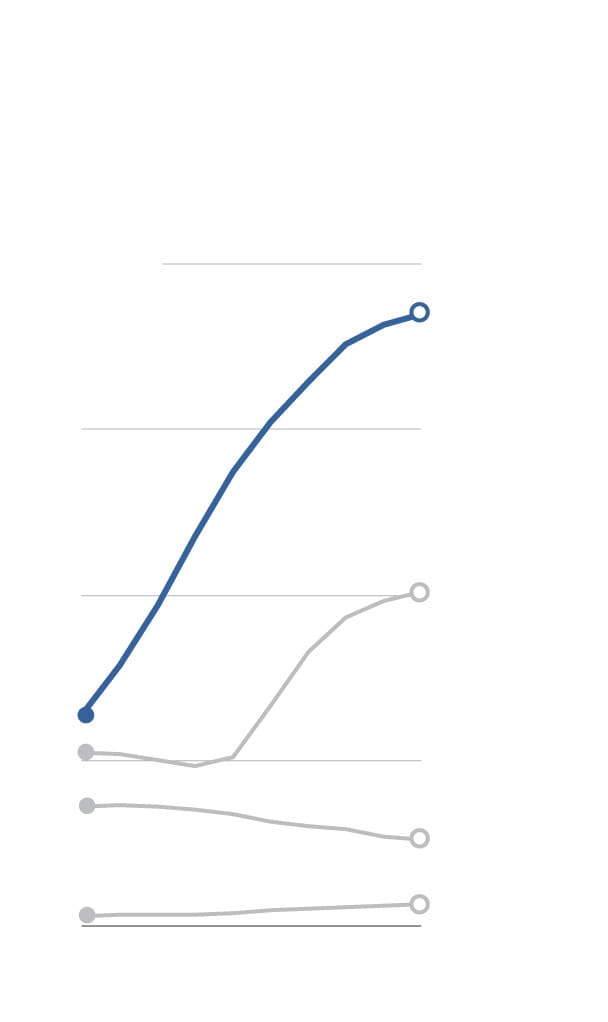

Surge of Chinese students to

the U.S. is tapering off

The number of Chinese students in the U.S.

nearly tripled over 10 years, but growth is

slowing.

400,000 students

China

369,548

India

202,014

South Korea

52,250

Nigeria

13,423

Source: Institute of International Education

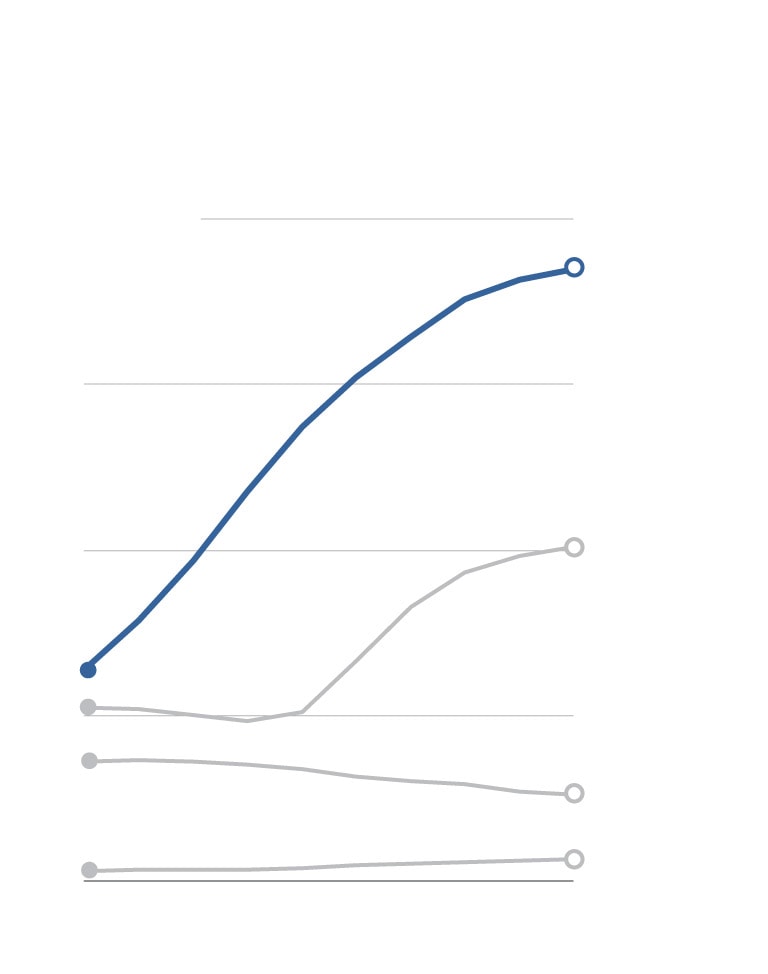

Surge of Chinese students to the U.S.

is tapering off

The number of Chinese students in the U.S. nearly

tripled over 10 years, but growth is slowing.

400,000 students

China

369,548

India

202,014

South Korea

52,250

Nigeria

13,423

Source: Institute of International Education

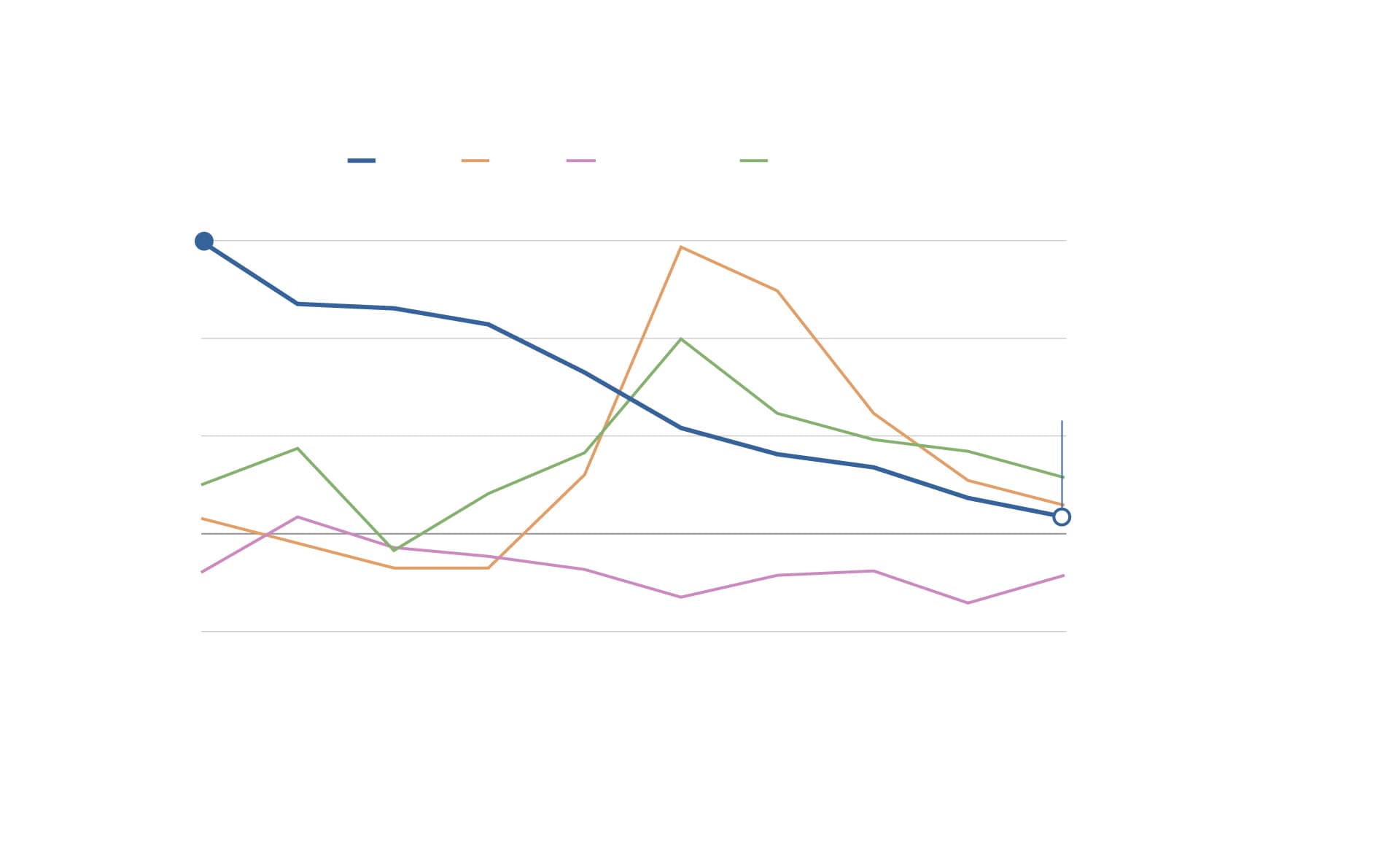

Surge of Chinese students to the U.S. is tapering off

The number of Chinese students in the U.S. nearly tripled over 10 years, but growth is slowing.

400,000 students

China

369,548

India

202,014

South Korea

52,250

Nigeria

13,423

Source: Institute of International Education

South Korea

29.9% increase in

students from China

Increase in students

1.7% increase

Decrease in students

Universities knew the boom would not last forever, but few anticipated the impact of tough talk and visa threats from President Trump — not to mention a pandemic.

“This has not been the easiest admissions cycle, that’s for sure,” said John Wilkerson, assistant vice president for international services at Indiana University.

Gavin Newton-Tanzer, the co-founder and president of Sunrise International, a company that works with Chinese students and foreign schools, said that for the last few years most Chinese families had taken a long view, wagering that the political vitriol would pass and a U.S. degree would pay off long term.

“But there is a threshold,” he said, “There is a point where they are going to be like, ‘I’m done.’”

Global distancing

This is Part in a series of stories on how the coronavirus is disrupting an interconnected world.

That moment may be drawing nearer. As Haila and Jingchu powered through their senior years at different Beijing high schools, they mostly focused on essays and applications, not great power politics.

Haila daydreamed about watching college basketball and trips to Chick-fil-A in Charlottesville. Jingchu pre-wrote a social media post for acceptance day: “stay true to your mission.”

But by spring, as they waited for their big moment, the crisis unfolding in the United States became impossible to ignore. “I could never have imagined any of this,” Jingchu said.

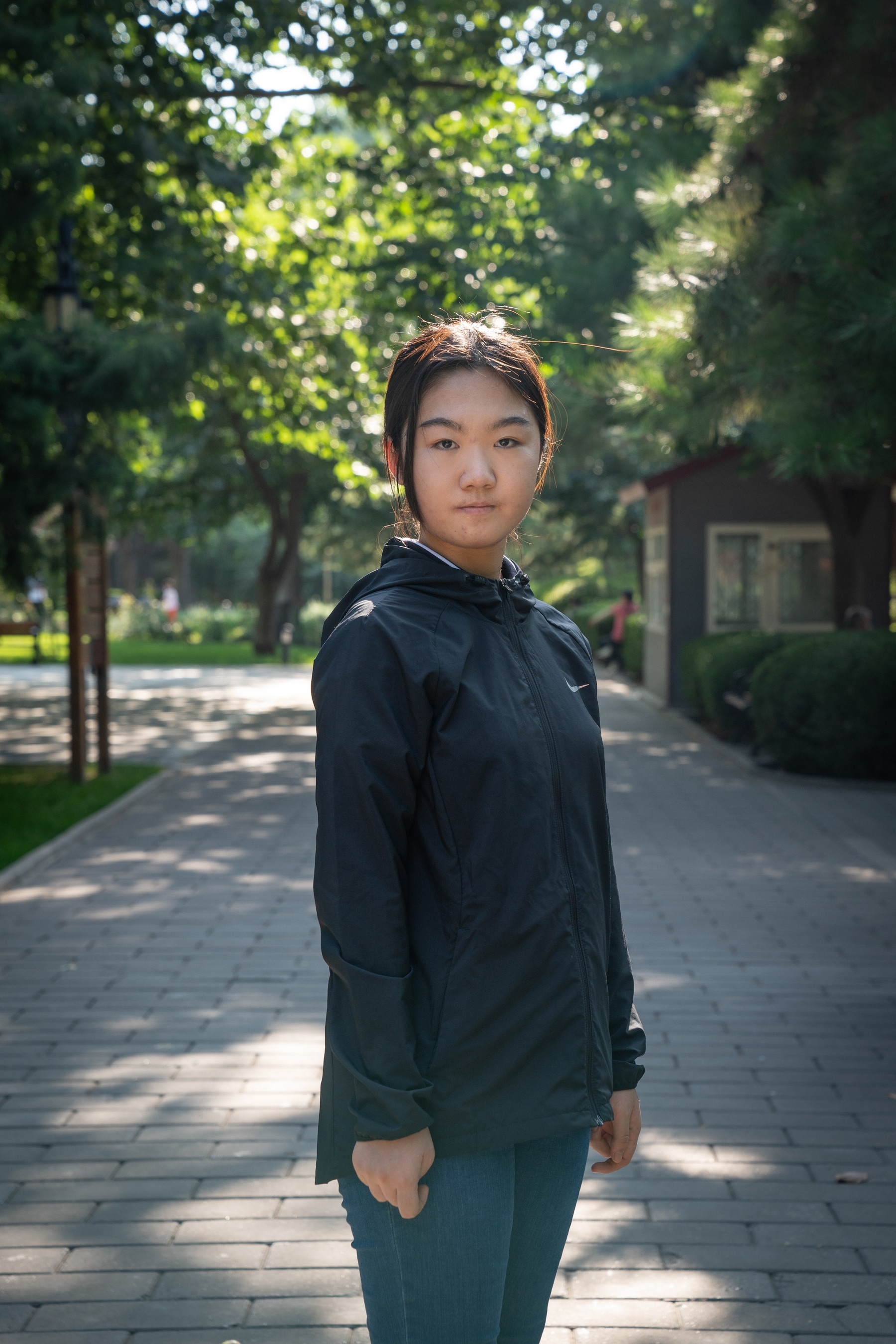

Their American Dream

For Haila and Jingchu, like many incoming Chinese undergraduates, the road to an American education started in childhood.

They met at a Beijing primary school. She was outgoing. He was bookish. They joke now that they were both popular — just in different ways.

In elementary school, good grades make you a certain kind of popular, Haila said. Jingchu was that kind of popular. Jingchu remembered Haila as extroverted and social: “American popular,” he quipped.

“It was very unrealistic to imagine the states as such a fancy country.”

Haila Amin

By the time Haila entered middle school, she was one of a growing number of Chinese kids hoping to one day study in the United States.

In 2002, the year she was born, just under 65,000 Chinese students went to study in the United States. When she started middle school in 2014, there were more than 300,000, according to IIE.

The surge was part push, part pull. Many families were frustrated by China’s relentlessly competitive school system, where every year of schooling builds toward the national college entrance exam. As the economy expanded, more families could afford to explore options abroad.

American institutions offered a different, more flexible style of education. Tuition was steep, but a U.S. degree was seen as a good investment — and something of a status symbol.

In the smoggy winter of 2014, Haila decided to get a head start on her American dream.

She enrolled the next fall at a private school in Virginia. “Back then, I thought the U.S. was extremely prosperous and people were super kind, super rich — that it was the greatest king of this world,” she recalled.

The reality was different. There was much she liked, but she missed Beijing. After a year and a half, she went home.

The Chinese education system is like a highway that runs from elementary school straight through to the college entrance exam. By exiting early she had all but eliminated the path to a Chinese university.

She enrolled in the international division of a local high school and set her sights on returning to the United States, ideally to Virginia, where she still had friends. “The moment I returned back to China I was aiming to go back to the states,” she said.

Her old classmate, Jingchu, would soon be on a similar path.

“This pandemic definitely disillusioned us about the United States.”

Jingchu Lin

After primary school, he enrolled at one of Beijing’s best middle schools. He initially assumed he would follow generations of great scholars to Peking or Tsinghua, China’s top universities.

But in his last year of middle school, he started to consider the freedom that might come with studying elsewhere. His mother encouraged him. “She brainwashed me into believing the U.S. system was better,” he said.

He chose the international division of a top-ranked high school and set his sights on the Ivy League.

First signs of trouble

For a couple of years, Haila and Jingchu kept in touch the way many teenagers do: following each other’s social media posts without actually talking much.

In the summer of 2018, they reconnected in real life at Yale Young Global Scholars, a summer enrichment program in Beijing that features lectures by Yale faculty and excursions around town.

“The kind of program that tries to make some money from Chinese students,” Jingchu joked.

Training, recruiting and educating Chinese students was by then a huge, but slowing business.

Part of the problem was politics.

The Trump administration’s immigration threats led parents to worry about student and work visas.

They also asked a lot about gun violence, said Lukman Arsalan, inaugural dean of admission at Franklin & Marshall College. “I’m seeing, just in the past three years, more interest from Chinese students looking at the U.K., Australia and Canada. Students have been frank about it,” he said.

That summer, as Haila, Jingchu and other young scholars mulled “Asia in the 21st century” with Yale faculty, the U.S.-China trade war raged and Chinese students got caught in the crossfire.

The U.S. State Department started to shorten visas for Chinese graduate students in certain fields, citing national security concerns. Trump reportedly told a group of CEOs, without citing evidence, that almost all Chinese students in the United States were spies.

That fall, as they entered their junior year of high school, there were reports that the administration was mulling a total ban on Chinese enrollment.

Not long after, news broke that the business and engineering colleges at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, known for having a huge number of Chinese international students, had taken out an insurance policy on its Chinese student population.

If enrollment dropped 20 percent, the colleges would be covered for $60 million. Jeffrey Brown, dean of Gies College of Business, told Inside Higher Ed at the time that it was to guard against “a visa restriction, a pandemic, a trade war.” (Brown declined to comment on whether the policy had kicked in, citing a confidentiality agreement.)

For Jingchu, Haila and many others, there was no insurance policy. They were already years down the road to a U.S. education.

They put their heads down and kept working.

‘Don’t go to the United States’

On March 26, 2020 Jingchu stayed awake for 24 hours, then checked a selection of the schools he applied to — Duke, Cornell — saving Yale for last.

When he saw the good news, he yelled to his parents, called his headmaster, then posted the news to WeChat. He remembered thinking to himself, “I am now able to dictate my life.”

He knew he would accept the offer. He ordered himself a celebratory pizza, then fell fast asleep, exhausted by years of work and worry.

For Haila, the moment of elation and relief she imagined did not come right away.

In late March, she was accepted to one of her safety picks, the University of California at Santa Barbara and wait-listed for her first choice, the University of Virginia.

“Okay, they didn’t reject me,” she thought to herself.

A few days later, she learned she was offered a spot in a joint program between Columbia University and Sciences Po, in France — a backup option she had applied to “for fun,” she said.

Haila had been hoping to make a triumphant return to Virginia, where she attended middle school. The leafy campus seemed to epitomize U.S. college culture; she could not wait to watch U-Va. play Duke or Notre Dame.

But the chaos unleashed by the pandemic changed her priorities. By the time her offers were in, the coronavirus was laying siege to New York City. She started to wonder if the United States was safe.

Every day, there were stories in the Chinese press about surging case counts, protests and anti-Asian violence. When Haila left her Beijing apartment building, the security guard warned her about the United States. Her extended family in Inner Mongolia did too. “Don’t go to the United States, go anywhere but the United States,” they said.

Instead of waiting to hear from U-Va., she opted for the Columbia-Sciences Po program, which starts with two years in France. It would keep her from America’s coronavirus chaos, save tens of thousands of dollars on her first two years of tuition — and still get her the name brand, U.S. degree she craved.

She posted the news to WeChat, just as she’d once imagined, but felt a tinge of regret. “I really wanted to go to U-Va.,” she said.

By May, Eli Lam, an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan who runs the school’s Chinese Students and Scholars Association, was fielding frantic queries from parents.

They messaged him about medical supplies, supermarket shortages and the protests then rocking several American cities. “They were asking us, how can our kids live there?” he said.

Gloria Chyou, the co-founder of InitialView, a company that interviews international applicants to U.S. institutions, said the parents of Chinese high school juniors were also concerned.

By June, it was tough-to-impossible to get a visa and flights were still scarce. Jingchu realized he might not make it to New Haven by fall.

Haila, meanwhile, was prepping for France.

“The French Embassy is open,” she told Jingchu.

“I’m jealous,” he said.

Hope and regret

The summer brought little respite.

The pandemic raged on, with a second lockdown in Beijing and spikes all across the United States.

On July 1, Yale said it would reopen in the fall with a mix of online and in-person classes, but Jingchu did not see how he could get to campus — or if he wanted to.

His parents were nervous about the idea of him traveling to New Haven. He did not want to take a gap year because it would only “extend the uncertainty,” he said. That meant online classes — not great given the time difference, but doable.

Days later, the U.S. announced that foreign students would not be admitted to the United States if they were only taking online courses.

International students typically must attend most courses in person, not online, to be admitted to the United States. But, through the spring, the rule was not enforced. The new directive seemed to suggest that international students could be deported if their schools did not reopen.

“This is appalling,” Jingchu said.

It was not immediately clear what the measure meant for students who either could not get a visa or did not want to go to the United States in the middle of a pandemic. “I’m not sure if this might mean I need to go to the United States to earn credits,” Jingchu said then.

In China, people joked that the United States was offering Chinese students complimentary “patriotic education” by making them appreciate the motherland and doubt the U.S. It felt, Jingchu said, like the United States was treating Chinese students as “disposable.”

After swift pushback, including a lawsuit from Harvard and MIT, the United States rescinded the directive. Then, in late July, immigration officials issued new guidance, saying the rule against a 100 percent online caseload does, in fact, apply to new students.

With just weeks to go, Jingchu is still trying to gather information about what comes next.

Karen Peart, director of university media relations for Yale, said the school understands that many incoming Chinese students have not been able to get visas. But, she added, Yale hopes they will be able to make it to campus in the first few weeks of fall semester.

Yale will be offering some in-person courses for new students, she said. Those who are unable to get to New Haven can take courses online.

Jingchu’s plan is to study remotely, keeping U.S. hours as necessary. Studying online is not what he signed up for, but he will “put up with it,” he said, “along with many other things.”

He has connected with other Chinese students who are stuck in China. “This pandemic definitely disillusioned us about the United States,” he said.

Haila’s regret over missing out on U.S. campus life has faded. She will not get cheerleaders or collegiate basketball, but she will get weekend trips to European capitals.

“It was very unrealistic to imagine the states as such a fancy country,” she said.

She wonders if younger Chinese students will have the same enthusiasm for American colleges that she once did. Juniors at her high school will probably apply to several countries, just in case, she said.

She is hoping to get to France by September, October at the latest.

“I don’t think my American dream is broken,” she said. “It just needs time.”