Japan has the world’s oldest population. Yet it dodged a virus crisis at elder-care facilities.

Japan has the world’s oldest population, with an average age of 47 and a life expectancy of more than 81 years. More than 28 percent of its people are over the age of 65, ahead of Italy in second place with 23 percent, and compared with 16 percent of Americans.

It could have been sitting on a coronavirus disaster, with the pandemic hitting seniors particularly hard, especially those in group facilities.

But Japan has recorded 1,225 deaths from covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, compared with nearly 180,000 in the United States. In Japan, 14 percent of the deaths were in eldercare facilities. That is compared with more than 40 percent in the United States, despite a lower proportion of U.S. seniors living in nursing homes.

Fewer than 1 percent of Americans live in nursing facilities, compared with 1.7 percent in Japan.

The disasters that unfolded in nursing homes in the United States and Western Europe during the pandemic have exposed the neglect and underfunding that have bedeviled elderly care in much of the West. Japan’s more positive experience may offer important lessons for the entire industry as it reviews policies and protocols for the next possible world health crisis.

Ready for pandemic

The contrast is partly because Japan reacted more quickly than Western nations to developments in nearby China, and swiftly tightened controls on staff and visitors at its eldercare homes, said Reiko Hayashi, deputy director general of the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

But culture also appeared to play an important role: Experts point to a higher priority given to elderly care within society, stronger measures already in place at care homes to prevent infections and high standards of hygiene.

“Japan’s elderly care facilities have taken great care in protecting the elderly, not just from this virus but from norovirus, influenza and other germs,” said Kayoko Hayakawa, an infectious-disease specialist at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGHM). “Day-to-day precautions were already in place.”

At the Cross Heart home in Kawasaki, south of Tokyo, controls were tightened in early February as caregivers watched with alarm the unfolding crisis in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

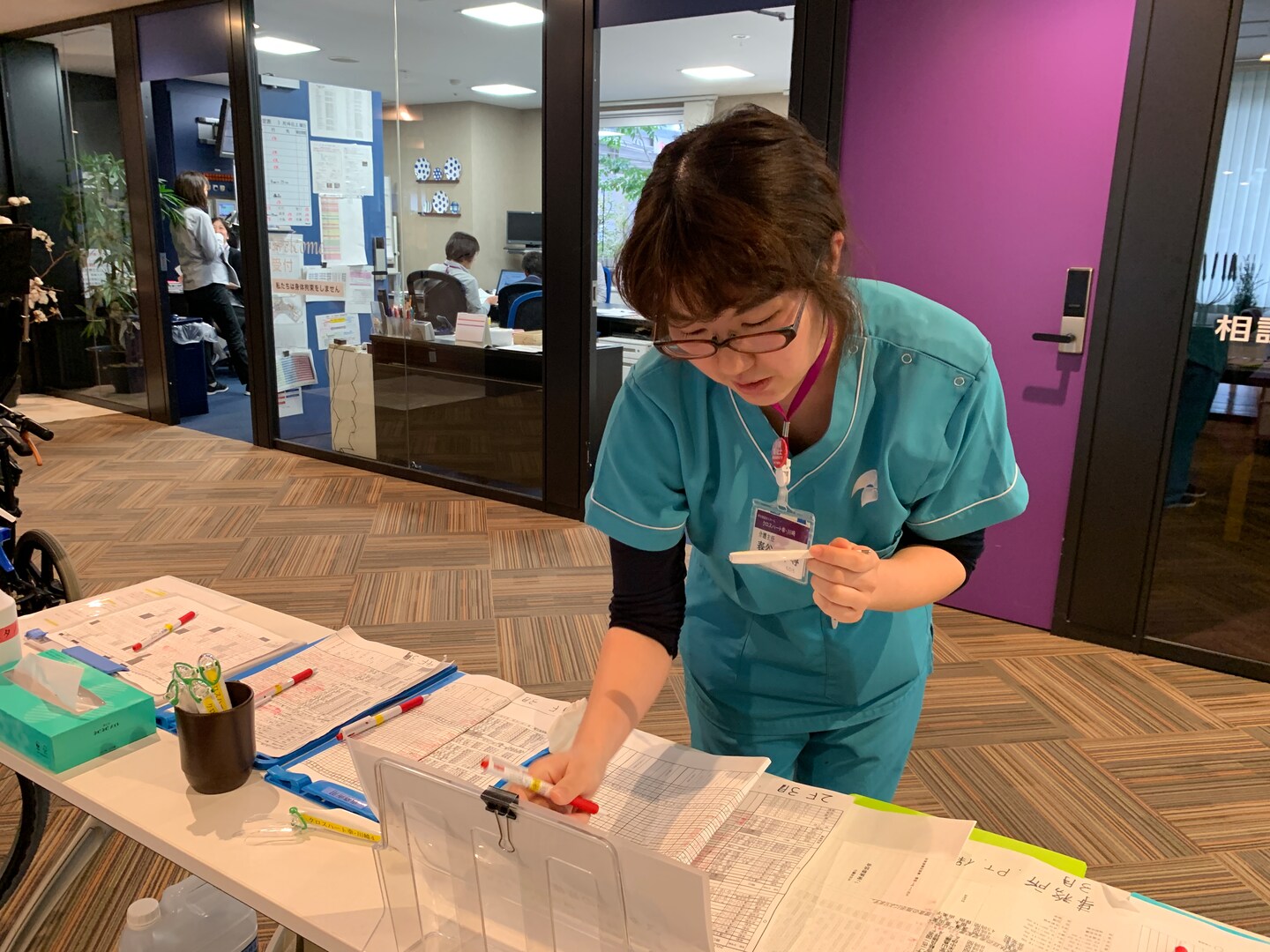

Staff and visitors disinfect their hands, take their temperatures and fill in forms about their recent medical history before they enter the spotlessly clean cafe and administration facilities on the ground floor.

Access to the second floor, where residents live, is very closely controlled, with even close family members excluded — except in cases where a patient is near death, when one or two close relatives are allowed to visit.

“Because we work in this type of facility every day, we are always aware of the risks of norovirus or influenza, and we became conscious of the impact of coronavirus pretty early on,” said chief caregiver Chihiro Kasuya, speaking in mid-March, when a Washington Post team visited the center.

“The very basic principle of elderly care is washing your hands at each step of your work: Take care of someone, wash your hands, do another job, wash your hands. But now it is even more thorough.”

No masks for staff

Perhaps surprisingly, staffers don’t usually wear face masks. It makes it harder to communicate with elderly patients who may be suffering from dementia, explained the home’s manager, Masayuki Mori.

Instead, the idea is to keep the infection out in the first place.

It’s a similar story at Tsukamoto’s home — the Life & Senior House Ichikawa, run by Haseko Senior Holdings, where manager Takao Furusawa says he owes a huge debt of gratitude to staff who have basically put their own lives on hold so they don’t bring the virus in.

“They have hardly been anywhere else except here, and just commute between their homes and work,” he said. “They have taken their responsibility very seriously. That’s humbling to me.”

In Japanese tradition, the job of caring for the elderly would fall on the eldest son’s wife, and there was social stigma around the idea of placing relatives in a nursing home.

That changed after the introduction of long-term care insurance in 2000, with a tax levied on everyone over the age of 40 to pay for elderly care. But there is still a level of expectation within society that elderly people should not be neglected, and that care homes should be carefully regulated.

In the United States, even before the coronavirus pandemic, about 4 in 10 nursing homes were cited for infection control violations, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office, and around 380,000 residents died of infections each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Japan’s nursing homes are not without staffing problems, and controls were far from perfect when the coronavirus struck. More than 100 clusters of cases have been identified at elderly facilities, the Health Ministry says, and a wave of infections almost overwhelmed the system in April.

At one home in the northern city of Sapporo, 71 residents of a single home were infected with the virus and 12 died; infected people were not hospitalized, but left to be cared for in the home.

City authorities, who had promised support, sent just one doctor, according to a report by broadcaster NHK. In addition, most of the home’s staff were sent home to be quarantined because they had been in “close contact” with infected patients — leaving just a handful to cope with both sick and uninfected residents.

Link to obesity

Although Japan has experienced more coronavirus deaths per capita than many countries in the region, it has recorded far fewer deaths than many Western nations.

Better protections for the elderly helped, but one key reason is that Japanese people have significantly lower rates of obesity than Westerners, according to a study by NCGHM.

“We tend to have less diabetes, less obesity, and these kind of risk factors seem to be heavily related to the severity of the disease,” Hayakawa said.

The tight controls implemented by Japan’s eldercare centers also came at a cost, said Seiko Adachi, a senior executive at Shinko Fukushikai, the company that runs the home in Kawasaki and many others.

“It is causing isolation, and for some people a worsening of their dementia,” she said, explaining that not all the elderly understand why their family members are suddenly staying away.

Staff at both homes do help residents connect with relatives via video links, but it’s not the same. Tsukamoto had been looking forward to decorating her new room at the residential home with her daughter. “She’s really good at that,” she said. “I feel very lonely.”

Mealtimes are no fun either, since the home has spaced residents out in the dining room.

“It’s really no fun to eat by myself, whatever I eat,” she said. “There was a moment during mealtimes when I thought it got too noisy. But now, I really miss that.”